Visual Arts Review: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater — Brilliance Beyond Myth

By Mark Favermann

20th-Century Modern Architectural Greatness

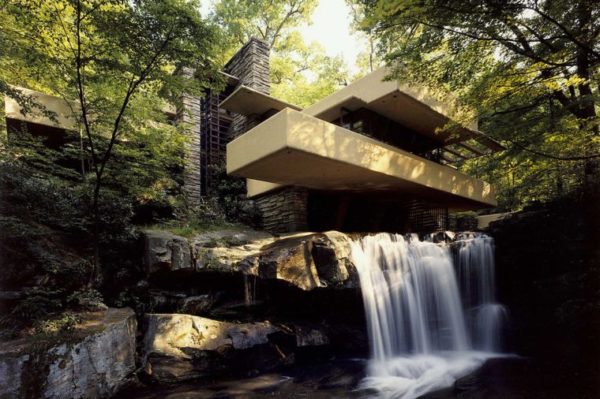

A view of Fallingwater. Photo: courtesy of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

When wealthy Pittsburgh department store owners Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann called Frank Lloyd Wright to tell him that they were on their way to see the plans for their weekend home Fallingwater, the procrastinating architect drew up the full set of drawings in about two hours and presented them as a finished package. Legend has it that Wright had the complete concept in his head; he had to just rapidly set it down on paper. I doubt if this is what really happened.

This would be like Ludwig van Beethoven writing his Symphony No. 9 in D minor in a couple of hours without any revisions, or Michelangelo carving David in an extended afternoon without any wayward chisel marks. It couldn’t be done. What probably happened was that Wright and his apprentices had done a number of preliminary sketches in rough and then more refined forms. When the Kaufmanns called to say they were on the way, Wright had everyone stop what they were doing and completely finish the drawings. Arguably, the project, completed in 1937, became the greatest house design of the 20th century.

Wright might have come up with a few innovative wrinkles during the rushed drawing phase of the plans. That often happens during the creative process. An apprentice or three, enamored with the master, verified Wright’s story of putting ideas to paper at supersonic speed. Thus, the myth was born: like Athena from the forehead of Zeus, Fallingwater sprang miraculously from the head of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Several years ago, I visited Fallingwater. It is magnificent. Though a bit smaller than what I expected, it is architectural genius. Wright got it right. By the ’30s, his professional if not chronological contemporaries — Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe — had taken modern architecture beyond what Wright had done earlier in the 20th century. They had created a sparer, more rigid geometry of space and form. With Fallingwater, Wright met their challenge and then some. There was a human warmth and connection to nature in his design that went beyond pure abstract design elegance. This project was the one that put Wright back to the apex of the architectural pyramid.

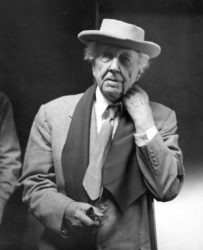

Frank Lloyd Wright. Courtesy of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Wright’s return to prominence started in 1928 when he was around 62 years old. His third wife, Olgivanna, was 30 years his junior, and she aggressively assisted him in marketing and selling himself. In 1932 he published An Autobiography, establishing the Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin and later in Arizona that same year. Wright generated an income from his apprentices. They learned from the master as they worked for him. They also served as a vehicle to spread his theories on architecture, urbanism, and nature. Wright delivered paid speeches during that period; they were provocative and entertaining. These lectures spread the Wright word as they projected a notorious public image: the dramatic, all-knowing, and often boastful Frank Lloyd Wright.

One of the apprentices captivated by Wright’s 1932 autobiography was a young art and design connoisseur by the name of Edgar Kaufmann Jr. He was not interested in the manual labor required of the other apprentices. But the young man owned a new car that he used to pick up potential clients who were scheduled to see Wright. More important, he introduced the architect to his wealthy parents in 1934.

The first project Wright completed for the Kaufmanns was a 1935 redesign of the offices at Kaufmann’s Department Store in downtown Pittsburgh. These elegantly distinctive, mostly wood interiors are now part of the permanent exhibits at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Wright worked on a number of potential projects for the Kaufmanns, but only the office interiors, Fallingwater (1937), and the Fallingwater guesthouse (1939) were ever built. Yet these structures were enough to resurrect his career. The majority of Wright’s approximately 350 building commissions came after this time.

It has been said that Fallingwater is the perfect marriage of building structure to site. Spectacularly built over a waterfall, there are layered ledges that reflect the strata of the site’s sandstone. With interiors open to the natural setting, the spaces in and around the house cast a magical spell.

Unlike many of Wright’s clients, the Kaufmanns challenged Wright during the design process and were able to add and subtract elements to his design. Wright tended to dictate to, rather than work with, his clients. Ironically, I feel that his collaboration with the Kaufmanns led to the greatness of the result.

A view of Fallingwater’s interior. Photo: Robert P. Ruschak, courtesy of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Fallingwater’s interior spaces reflect this give and take. Typical of Wright are the surface elements, the natural color palette, indirect lighting, spacious open rooms, defined activity areas, and fine craftsmanship. The Kaufmanns gave the house a lived-in warmth, insisting upon their own choices of furniture, modern bathroom conveniences, and an abundance of storage.

The natural color scheme is invigorated by Wright’s favorite color, Cherokee Red, applied to windows and various items around the house, including a large kettle used for brewing hot drinks. The inside/outside synthesis of the house underscores Wright’s involvement with nature as well as the Kaufmanns’ early preference for conservation.

The house is a home for all seasons. Fallingwater reflects and frames views of the natural environment in dramatic ways throughout the year. And it served the Kaufmanns as a real vacation getaway, a retreat for family, friends, and corporate employees. It is located at 1491 Mill Run Rd, Mill Run, in southwestern Pennsylvania, 43 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

After a career as an assistant curator of design at the Museum of Modern Art and a long tenure teaching at Columbia University, Edgar Kaufmann Jr. donated Fallingwater and its over 1500 acres to The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in 1963.

In recent years the house required extensive structural support work, including window replacement and concrete surface repairs. The damage was the result of Wright’s indifference to standard engineering and the inevitable byproducts of age. These repairs and refinements have been completed with stunning success.

Fallingwater underscores Frank Lloyd Wright’s greatness. In the early 1990s, the American Institute of Architects named him the greatest American architect. The building was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program. Since 2002, Mark has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.

Hi, Mark,

So glad to see your lovely piece about Fallingwater which is dear to my heart, since my husband, Robert Silman, who died in 2018, was the great structural engineer who did the most important fix to the house in 2002.

The world of ArtsFuse is a small one, indeed.

Best,

Roberta