Arts Remembrance: Poet Mary Oliver

By Robert Israel

Mary Oliver’s poetic vision reaches back to the American transcendentalists: it encourages us, by demanding that we pay attention to our now threatened natural world, to find a moral compass.

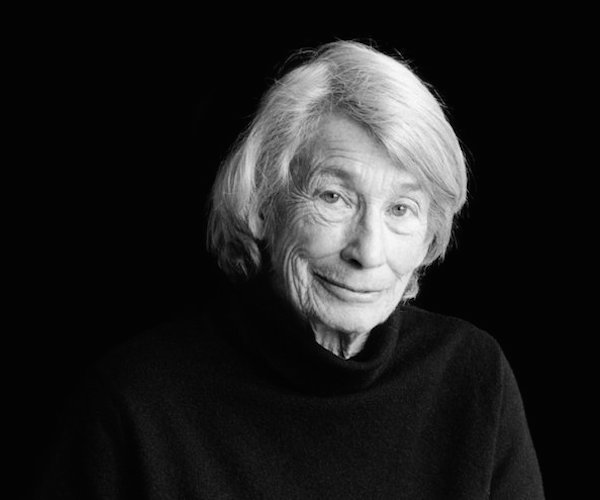

The late poet Mary Oliver. Photo: Wiki Commons

I’ve been a seasonal visitor to Provincetown from my teenage years onward; each summer I’d glimpse reclusive Mary Oliver, the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet who died this week from lymphoma at age 83.

She turned me down for a formal interview when I approached her after a public reading at the town library. But if I sighted her going in or out of the shops on Commercial Street, the honky-tonk main artery that hugs Provincetown harbor, we’d chat amiably. The last time we met was a few summers ago, in front of Spank the Monkey, a tawdry gift shop. The owners had lit a bunch of sage on the sidewalk; the pile was coughing up smoky fumes that smelled like cannabis. She found this amusing, especially when tourists leaned over to inhale the smoke in hopes of getting high. We chatted while she stood astride her beat up Schwinn bike. She puffed on a cigarette. Her mop of grey hair was askew. Her teeth were yellowed from nicotine. Her faded blue sweatshirt matched her eyes.

I wasn’t the only reporter she dismissed. She said no to the New York Times, forcing the writer to prowl around the town and its national seashore to find the sites of Oliver’s poems that faithfully describe the flora and fauna of the Outer Cape.

She told Maria Shriver, in a rare interview in O Magazine, that it wasn’t because she was reclusive; she found press interviews distracting:

“I didn’t know I was a recluse. I mean, I know many people in Provincetown — fishermen, Portuguese people, young people,“ she told Shriver. “If the plumber says, ‘How’s your work goin’?’ I’m very easy with that. But if somebody I don’t know comes to town and calls me up and says, ‘I love your work. I’m here for three days, could I take you to lunch?’ — well, that is something I can’t do. It’s hard to meet a stranger—you give of yourself—and if I did that, I’d want to do it well. I’d have to leave my desk, or the woods, and I don’t want to.”

Oliver claimed to have been influenced by American poets Walt Whitman and Edgar Allen Poe; she wrote essays about each of them in one of her last books, Upstream: Selected Essays. But the writings of American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson were her greatest inspiration, principally because he preached that we must live the kind of awakened lives that embrace a “moral purpose”:

“The one thing he is adamant about,” Oliver wrote in “Emerson: An Introduction,” “ is that we should look — we must look — for that is the liquor of life, the brooding upon issues, that attention to thought even as weed the garden or milk the cow.”

It is this thread — of living an awakened life with what American poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti called “an open eye and an open heart” — that one finds woven throughout Oliver’s poems.

In the last lines of one of my favorite poems, “Mornings at Blackwater,” Oliver drinks from one of the small kettle ponds near the bicycle path leading to Race Point beach. She writes:

“What I want to say is/that the past is the past,/and the present is what your life is, / and you are capable/ of choosing what they will be/darling citizen./So come to the pond/ or the river of your imagination,/ or the harbor of your longing,/ and put your lips to the world. /And live your life.”

— “Mornings at Blackwater,” from Red Bird (Beacon Press, Boston).

Mary Oliver’s poetic vision reaches back to the American transcendentalists: it encourages us, by demanding that we pay attention to our now threatened natural world, to find a moral compass.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.