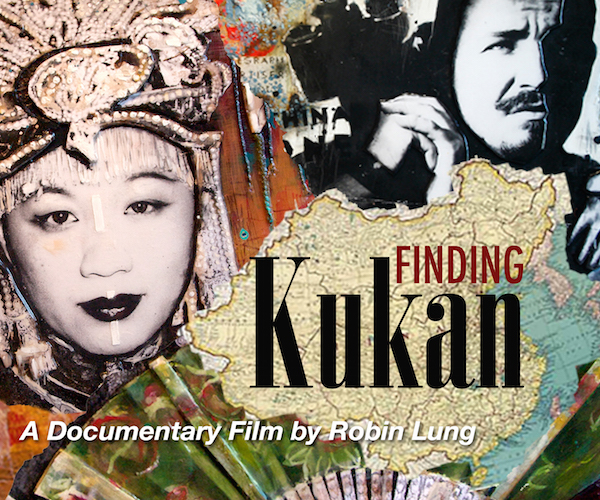

Film Review: “Finding Kukan” at the BAAFF — A Compelling Detective Story

Finding Kukan is a compelling detective story covering the fields of World War II history and film preservation, where it’s always a race against the ravages of chemical deterioration.

Finding Kukan, directed by Robin Lung. Screening at the Bright Family Screening Room, The Paramount Center, 559 Washington Street, Boston MA, as part of Boston Asian American Film Festival on Saturday, October 21 at 1 p.m.

By Betsy Sherman

The new feminist badge of honor “nevertheless, she persisted” (thanks, Mitch McConnell) can be pinned twice over, on documentary Finding Kukan’s subject, the late Li Ling-ai, and on its maker, Robin Lung. The film is a compelling detective story covering the fields of World War II history and film preservation, where it’s always a race against the ravages of chemical deterioration. It’s important in shining a light on unsung women in the history of American film, the saga of the Chinese in the United States, and attitudes towards Chinese-American women in particular. Plus the vivacious Li Ling-ai is a pleasure to get to know.

The Kukan of the title is a 1941 documentary whose director, Rey Scott, received a special Academy award “for his extraordinary achievement in producing Kukan, the film record of China’s struggle, including its photography with a 16mm camera under the most difficult and dangerous conditions.” The color film, which witnessed the terror perpetrated on Chinese civilians by Japanese occupying forces, was made to influence American policy and sentiment. It wasn’t seen much, if at all, after the war and has been considered a lost film. Documentarian Lung, in trying to find out more about Kukan (its title meant “heroic courage under bitter suffering”), learned that a woman listed only as a technical advisor, Li Ling-ai, was likely the prime mover of the project. Moreover, Li probably performed the duties of a producer, without getting any of the credit (the man named as producer was merely the distributor).

The audience follows Lung on her investigation, during which she meets relatives of both Li (born in Honolulu in 1908 to a family of physicians), and the late Rey Scott, the white cameraman whom Li funded to go to China and bring back footage that would show Americans what was going on there. Li furnished Scott with connections to her family in Chunking; through this circle, he was also able to meet and film Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Soong Mei-ling. However, Kukan’s strong suit was that it showed a cross-section of life in various parts of the nation; the masses bore the brunt of the bombings.

Parallel to Lung’s research is the task of film conservators to restore, if possible, a print of Kukan that had been rotting in metal cans in the home of one of Scott’s sons.

Trailer for the feature documentary FINDING KUKAN. from Robin Lung on Vimeo.

Luckily for Lung, both Li and Scott had written memoirs, and some of their correspondence survives (Li’s words are voiced by Kelly Hu, Scott’s by Daniel Dae Kim.) Scholars were enlisted to fill in background information on the war and on legal obstacles faced by Asians in America. Newsreel footage includes shots of the United China Relief parade in early 1941; Li was active in the organization in New York, her adopted home as of 1940.

No one can deny Li’s megawatt personality. Her beauty, style, and especially her knack for getting publicity account for the abundance of stills and film clips that make her a lively presence on screen. Finding Kukan includes excerpts from an interview with Li filmed in 1993 when she was 85. Decked out in black and purple Chinese garb, she is one indomitable dame as she speaks about her partnership with Scott in getting Kukan made.

Yet when Lung speaks with Li’s nephew, who endured the war in China and now lives in the U.S., the octogenarian offers his view of Li’s role: “Is that true, or b.s.? She talked too much. Talk, talk, talk.” Words of an older man with a knee-jerk dismissal of women? They do have that familiar ring. But Lung, whose quest to tell this story took seven years, had to take them into account and continue to build a case. The filmmaker says, in voice-over: “I wanted Li Ling-ai to be the kind of heroine that no one would deny.” Lung succeeds in that crucial act of restoration.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Boston Asian American Film Festival, Finding Kukan, Ling-ai, Rey Scott, documentary