Dance Review: Red Deliverance

Screening at the Coolidge Corner Theatre on October 2nd, the Bolshoi’s Bolt is a curiosity worth exploring, a meditation on the Russian past that could only be produced after the nightfall of Stalinism. After all, in some eyes composer Dimitri Shostakovich may have been a stooge, but he was never an obtuse one.

Reviewed by Debra Cash.

In 1933 the Stalinist regime directed composer Dimitri Shostakovich to sign a statement that read in part “the depiction of Socialist reality in ballet is an extremely serious matter which cannot be approached superficially.” The composer was renouncing The Bolt, a mélange of a ballet that had its first—and only—performance in his lifetime at the Leningrad State Academy Theatre of Opera and Ballet in 1931.

The libretto by Viktor Smirnov is schematic in the extreme, a tale of heroic factory workers resisting industrial sabotage where stock characters fall to temptation and rise to reward. Even Shostakovich had to keep from yawning when he learned of the commission. According to biographer Laurel Fay, he described it this way: “The content is very topical. There’s a machine. Then it breaks down (problem of wear and tear on equipment). Then they fix it (problem of amortization), and at the same time they buy a new one. Then everyone dances around the new machine. Apotheosis. All this takes three acts.”

Stalin and his five year plans may be gone, but The Bolt is back. In 2006 the Bolshoi Ballet and Orchestra mounted a new production in honor of Shostakovich’s centennial. The production, filmed that September, is the inaugural event in this season’s “Raising the Barre: Ballet from Around the World” 2010–2011 HD broadcast showcase at Brookline’s Coolidge Corner Theatre.

The series has a heavy Russian accent. In February the Kirov (aka Mariinsky) Ballet flashes back to the Ballets Russes in an all-Stravinsky program with Firebird, The Wedding (known in the West as Les Noces), and The Rite of Spring, followed by a March screening of a reconstructed version of The Flames of Paris. The season is filled out with presentations from Britain’s Royal Ballet: Nutcracker for Christmas and Giselle in the spring.

The Bolshoi Bolt is a curiosity worth exploring, a meditation on the Russian past that could only be produced after the nightfall of Stalinism. After all, in some eyes Shostakovich may have been a stooge, but he was never an obtuse one. The year he worked on The Bolt intellectuals were being rounded up and sent to labor camps in the gulag. Half a million workers marched on Moscow to call for the execution of a group of technicians accused of sabotaging factories and plotting to overthrow Stalin—a conspiracy which may or may not have actually occurred. (This historical context comes from the useful chronology printed at the back of Ian MacDonald’s 1990 The New Shostakovich.

Many intellectuals emigrated; a few, like Mayakovsky, took another route of escape and shot themselves.

By reviving this lost work, the current administration of the Bolshoi simultaneously pays tribute to its past and casts a gimlet eye on those bitter, now nearly incomprehensible days. You almost hear the planning meeting with suave, contemporary artists shaking their heads exclaiming “what were they thinking?” while at the same time admitting some nostalgia for days when revolutionary art really meant something and the stakes for artists were high.

The Bolshoi Bolt is firmly set in the period of its creation. The curtain goes up on Semyon Pastukh’s overwhelming Constructivist factory where huge, riveted robots with glaring eyes guard the Means of Production like Cerberus standing in front of the gates of Hell. The odd man out is Denis danced by Denis Savin (apparently each character is renamed with the performer’s name, which is confusing if you want to buy a video because you’ll discover that all the characters have different names!). You can tell Denis is a clueless slacker because not only does he fall out of step with the coworkers with whom he is supposed to execute strenuous morning calisthenics, he wears different colored socks. And he takes a cigarette break on company time. Bad boy, Denis.

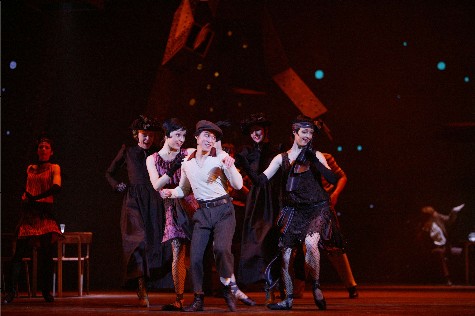

This square peg is in love with the elegantly long-legged Natya (Anastasia Yatsenko, in a demure dress), but you know she doesn’t want to be with him because when they dance together, she averts her eyes. She prefers straight-arrow Yan (the anemic Andrei Merkuriev—think Leslie Howard in Gone with the Wind). Denis stumbles into a bar, dances with some floozies, and meets a pickpocket, Ivachka (Morikhiro Iwata), who gives him the idea of sabotaging the machinery of his oppression with the euphonious bolt. Various things happen after which Denis manages to frame Yan, the plot is reversed, and we are treated to a series of divertissements featuring people on scooters, bathing beauties, and aviators. The People United Will Never Be Defeated.

Okay, that cranky tone is mine, not choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s. Ratmansky, who at the time directed the Bolshoi and now has raised his profile in New York with the New York City Ballet and American Ballet Theatre, doesn’t seem to be able to make a decision about whether he is playing this period piece straight—taking Shostakovich and Smirnov at their creaky Soviet word—or giving us a lens to use to think about what it all meant. On one hand the love story is done up classically, and it’s easy to relax into watching the superb technique of the Bolshoi’s huge cast. They could have stopped after Bolt’s opening calisthenics scene and I would have felt I had witnessed fine dancing.

The character dances in the bar, especially Alexander Voytyuk’s mincing Fyodor Beer, who could double for Leonid Massine in Gaite Parisienne, have an appealingly old-fashioned “look at me” bravura.

Ratmansky avoids some of Shostakovich’s most egregious bombast by paying attention to the composer’s organically shifting rhythms, played under Pavel Sorokin’s spirited baton. The camera crew’s uncredited decisions are well-informed but unexceptional; despite the vastness of the stage, I never got the sense that I was missing something important beyond the edge of the frame.

While high-def broadcasting is a boon for the sound of the orchestra and for seeing performers’ expressive faces, it is less than ideal for capturing movement. Anything fast—especially the dancers’ butterflying feet in batterie—creates ghosts on the screen. I don’t know whether conventional film stock would have made a difference, but the blur becomes distracting.

Ultimately, what’s most interesting about The Bolt is Ratmansky’s decision to stage the massive group scenes by turning undifferentiated workers into literal, cartwheeling gears and cogs. It’s a statement not unlike the now-campy Maoist ballets such as The Red Detatchment of Women, but in the Russian context it has a very special resonance. You start to see how the world of Bolt was presaged by the world of, say, Swan Lake. Those interchangeable swans in their regimented rows are somehow the prototypes for workers under a very different, malignant spell that we can be grateful has been broken.

The Bolt will be screened at the Coolidge Corner Theatre in Brookline, MA on Saturday October 2, 2010 at 11 a.m. For other national screenings, click here.

I very much look forward to seeing this, but it strikes me that it must not be very much like the work that was seen in 1931.

One can easily discern (from the photos above) that 21st Century stage design is adding significantly to the package. The bots’ body carriage, steam bath, and back lighting point more toward a pastiche of Michael Jackson videos, 1980s vintage Bayreuth, and the dream sequence from Oklahoma! than to a replication of the constructivist original.

In the resource and technology starved 1930s, it surely played as parody of the Utopian state, with sets that were as rattle-trap as the “modern” factories that they were portraying. The elite who were allowed to see the production must have cheered for the Bolt to win just this once…

Hi, Chris, thanks for writing in!

No question that this is Ratmansky’s complete overhaul and reinterpretation of a “lost” work—and that’s what makes it so interesting. I don’t think the Bolshoi tried to recreate the original sets, although there is a kind of riff on the Ballets Russes’ famous “Parade” with some yachts plastered with newspaper that accompany the exceedingly odd, bathing beauty scene. Happily, you can check that scene out on YouTube.

For the record, the producer/choreographer of the original was Fedor Lopukhov, whose aesthetic ran to formalist, totalizing “symphonic” and abstract effects. Accordingly, Bolt included stage formations “and multi-bodied, pyramid configurations representing the Soviet symbol of the star.”

The authorities were in no mood for satire. After the failure of Bolt, Lopukhov was asked to resign from the directorship Mariinsky, although he later came back. As I said, the stakes were pretty high.

I like your association with 1980s, vintage Bayreuth though. We’re all in the throes of living in our own cultural nexus. Going to see the HD broadcast of the MET Opera’s new Ring cycle?