Classical Music Review: Boston Musica Viva

By Caldwell Titcomb

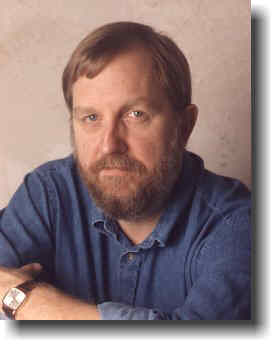

Richard Pittman ends the 40th season of the Boston Musica Viva on a strong note.

Back in 1969, Richard Pittman founded the Boston Musica Viva (BMV), the first local ensemble dedicated entirely to contemporary music. On May 1, Pittman and his colleagues wound up their 40th season with a concert of three works in the Tsai Performance Center – a world premiere, a revival of an earlier commission, and a celebrated masterwork.

The new piece came from Michael Gandolfi (b. 1956), who earned two degrees from the New England Conservatory, where he now heads the composition department. You will recall that Shakespeare’s Jaques in “As You Like It” famously tells us that “one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.” Gandolfi enlarges on this by entitling his work “History of the World in Seven Acts.” Or rather the enlargement was engendered by his collaboration with computer animator Jonathan Bachrach, who came up with seven “environments” outlining the history of a society.

Bachrach named the seven as follows: egg, anarchy, fabric, swing, imitation, follow, and escape. Gandolfi viewed his task as making “a connection between the visual, the aural, and the imaginings evoked by each.” Six musicians (piano, violin, cello, flute, bass clarinet, percussion) were down in the theater’s pit, and the stage was completely occupied by a huge white screen on which the images were projected.

Bachrach’s projections were polychrome geometric patterns, with an emphasis on whirling and swirling cubes of different sizes, sometimes isolated and sometimes concatenated. The result was engrossing throughout its twenty-minute length. (For those schooled in the technology — unlike me — the programming language used was called Proto, developed at the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.)

MIT’s Michael Gandolfi composed the evening’s world premiere.

The concert opened with “In Aeternum (Consortium IV)” by Joseph Schwantner (b. 1943). This 15-minute piece was premiered by BMV in 1973, six years before he won the Pulitzer Prize for his orchestral work “Aftertones of Infinity.” The composer says he used here a set of 36 pitches organized in an intervallically symmetrical cycle with each group of 12 tones appearing exactly three times.

The instrumentation calls for a cellist and four other players (flutes & piano; clarinets; viola & violin; and percussion). In addition, the musicians from time to time perform on antique cymbals (crotales), watergong, and crystal glasses whose edges are rubbed with wet fingers. The percussionist employs vibraphone, tubular bells, glockenspiel, tamtam, bell plate, and triangles. One tends to think of percussion as making a lot of loud noise. But here I was struck by how delicate the percussion writing was, such as a pianissimo roll on the tamtam. And the piece concludes with a lovely soft plucked chord on the cello.

Joseph Schwantner’s “In Aeternum (Consortium IV)” was also on the program.

The final work on the program was Arnold Schoenberg’s classic “Pierrot Lunaire,” Op. 21, dating from 1912. It reached its final form circuitously. The Belgian poet Albert Giraud (1860-1929) published a set of fifty poems in French (1884). Each poem had 13 lines (4+4+5), with the first line repeated as line 7 and 13 and the second line repeated as line 8. The fifty Symbolist poems were translated into German by Otto Erich Hartleben. Of these, Schoenberg selected 21 and bunched them into three groups of seven – dealing with love, violence, and finally the journey home.

The moonstruck Pierrot is the character familiar from the traditional commedia dell’arte. Some of the rather bizarre poems are Pierrot’s words, and some are about him. The moon is specifically invoked in eleven poems, and blood in six. Though Pierrot is male, Schoenberg intended his vocalist to be a woman (the work was dedicated to the first vocalist, whom the composer rehearsed forty times for the premiere).

A special feature of the work is the requirement that the vocalist neither sing nor speak the texts, but adopt a technique half way between, known as “Sprechstimme” (“speech-voice”). The notated rhythm is to be preserved but the written pitches are to be approximated via a general contour, creating what Schoenberg called “speech-melody” (“Sprechmelodie”). (Pittman’s program notes erred in stating that this was the first time Schoenberg used the technique, when it had also been employed in the composer’s earlier “Gurrelieder.”)

Five instrumentalists are called for: piano; flute and piccolo; clarinet and bass clarinet; violin and viola; and cello. The poems use varying combinations of instruments; only in the final number are all eight instruments specified. The musical style is atonal, but does not yet reflect the 12-tone serialism that Schoenberg would embrace in the 1920s.

All the players were back up on the stage. The vocalist was soprano Lucy Shelton, who stood on a raised platform. She has performed this work many times in the past, and here was wearing a brightly sequined floor-length gown. Her contribution was admirable all the way.

So influential was the scoring of this work that numerous other compositions used the same forces. An important offshoot was a touring ensemble called the Pierrot Players (established in 1965), which in 1970 was renamed The Fires of London under the leadership of Sir Peter Maxwell Davies. A staged version of “Pierrot Lunaire” remained in the group’s repertory until the ensemble disbanded in 1987.

Pittman conducted his musicians knowledgeably all evening, and everyone performed with unflagging precision. The expert instrumentalists were Ann Bobo, flute; William Kirkley, clarinet; Dean Anderson, percussion; Geoffrey Burleson, piano; Bayla Keyes, violin/viola; and Jan Müller-Szeraws, cello. The Boston Musica Viva’s fortieth season has ended on a strong note.