Movie Review: The World Goes “Tabloid”

The documentary TABLOID comes at an opportune time: an enigmatic look at one of the greatest tabloid stories of all time (the film will convince you of that) as Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid news empire melts down amid allegations of phone hacking.

Tabloid. Directed by Errol Morris. At the Kendall Square Cinema and other screens throughout New England.

by Taylor Adams

If you’ve been following world news, you’ll probably agree it’s been an interesting week for tabloid journalism of the British persuasion. In the midst of a protracted phone-hacking scandal, News of the World stopped its presses for good after 168 years of muckraking, celebrity expose, and overly assiduous reporting (to put it kindly).

It’s an anecdote that captures the essence of the public’s relationship to tabloid journalism worldwide: ‘tell me everything, except how you do it.’ The phone-hacking scandal broke in 2006 and probably reached much farther than News of the World, but the public seemed to tolerate these infractions as long as only celebrities, royals, and politicians were targeted. It wasn’t until recent revelations that the voicemail of a 13-year-old murder victim was hacked that things started getting ugly (unanimous uproar, official investigations) for Britain’s sensational press.

And all that time, papers were being sold. A lot of them. Wouldn’t this be a form of tacit public approval? Or at least a kind of cognitive dissonance, of wanting sensational stories but feeling uneasy about how the information was gleaned? It’s a case where money seems to speak louder than words.

Onto this scene bursts Errol Morris’s latest documentary Tabloid, a characteristically enigmatic look at one of the greatest tabloid stories of all time (the film will convince you of that): the “Mormon sex in chains” case of former Miss Wyoming World Joyce McKinney.

A quick “factual” primer: Southern beauty queen (McKinney) meets overweight, dubiously attractive guy (Kirk Anderson). Obsession ensues, but it’s one-sided in pretty much the opposite direction you’d expect. Also, Anderson is a Mormon, meaning he believes he’ll eventually inherit a planet in heaven and has to be whisked off to some holy mission in the U.K. without telling his newly infatuated girlfriend.

She decides to put together a team, including a bodyguard and pilot, to fly to England, kidnap the object of her affections, bring him to an idyllic country cottage, tie him up, and engage in a weekend of sexual re-education — ostensibly preventing him from joining the church via premarital copulation.

There was “something for everyone,” remarks one Morris interviewee who reported on the story for the Daily Mail, “It was the perfect tabloid story.” Tabloid is perhaps the perfect story about tabloids.

The film is composed of interviews with various stakeholders in McKinney’s story. One marathon interview with the star herself forms the backbone of the narrative, while conversations with journalists from two competing tabloids, the pilot Joyce hired, and an expert on Mormonism provide commentary and counterpoint to her tale and her version of events.

Unfortunately yet understandably absent are Joyce’s now-deceased sidekick Keith May and harrowed Mormon Anderson (not for lack of Morris wanting to interview him, we are assured).

It’s impeccably paced, fun, and visually snappy. Newsprint collage motifs abound, vignetting on file footage adds an aged look, tearing and typewriter sounds add impact to edits and to the attractive cut-out montages where photos and clippings from the tabloids are highlighted. Vintage film clips occasionally illustrate points. These are all welcome stylistic contributions to a movie where the most important content is a set of static interview scenes against a gray background.

Morris, as always, is audible both literally (his oft-heard voice, emanating from behind the camera, has a uniquely friendly-yet-assaulting quality) and in the film’s overall feel. In editing, the shots often linger long enough to show revealing reactions from its subjects. An added observation, a chuckle, a faint change of expression; so many years after these events, these people are just as surprised and amused at what comes out of their mouths as we are.

And why shouldn’t they be? As frivolous, absurd, and frequently hilarious as Joyce’s story may be — from the kidnapping to her arrest and the ensuing media frenzy, on to an addendum-like incident 30 years later where she again made headlines by being the first customer to have a beloved dog cloned by Korean scientists — its turns and twists are engrossing. This was, of course, why the story captivated U.K. tabloids for much of 1977.

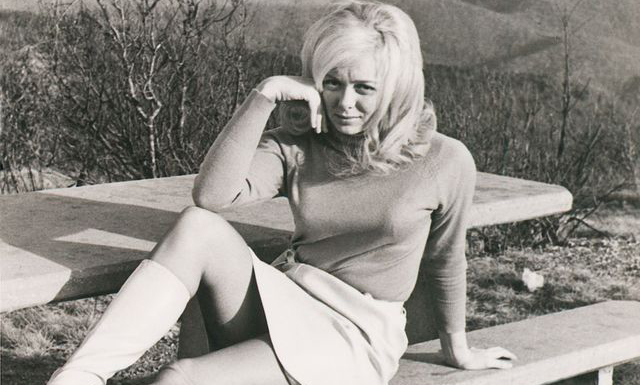

The subject of TABLOID: Southern beauty queen (Joyce McKinney) meets overweight, dubiously attractive guy (Kirk Anderson).

Or was it because of Joyce herself? Her easygoing southern drawl might tempt some to write her off, but this woman is very intelligent (she claims to have a 168 IQ), using her charming disposition as a tool of influence both during the incident and probably during her interviews in this film. “Thank god for all those years of drama school,” she says after describing her own ability to sway the crowd in a British courtroom.

The implications of such a statement could not have been lost on her, nor could those of the fact that she both apparently courts and loathes publicity. She deftly played the press during her legal troubles, and reveled in celebrity status at the time. Afterwards, though, she retreated to a rural life of seclusion with her parents, hoping to avoid reporters. She agreed to be interviewed for this film, but then spoke out against the finished product. She has showed up unannounced (sometimes with a dog) at screenings and Q&As to tell her side of the story or to argue with Morris.

There seem to be a few omissions on her part. The tabloid reporters, especially, paint a portrait of a slightly less stable Joyce who was manipulating them and others, and involved in a variety of incongruous activities including raunchy photoshoots advertising her licentious (though apparently sexless) escort services.

Morris is in his element here. Several of his films, and much of his recent writing for the New York TImes, have highlighted the mercurial nature of truth.

This film particularly echoes of Morris’ landmark 1988 The Thin Blue Line, in which the tales of a larger cast of interviewees (and stylized re-enactments) painted an ambiguous portrait of a police officer’s murder. In that case, there was a specific interest in finding some level of truth (an innocent man was released from death row because of the film).

Here, the stakes are much lower. Like most tabloid stories, the narrative is an entertainment that has few practical implications for anyone but the stakeholders. In this case, the bulk of the action took place so long ago that most of them have moved on or even died.

And so an objective truth doesn’t need to be found. But there’s a different kind of truth here among the oft-conflicting narratives of Joyce, the journalists, and the evidence. It’s the same theme found in Kurosawa’s Rashomon: the fact that history, far from being written, is subjective and probably impossible to pin down. There are probably as many truths about Joyce McKinney as there are witnesses to her tabloid saga (and there were many).

A year after films like Exit Through the Gift Shop and I’m Still Here challenged the idea of what a documentary was by playing with audience perceptions of reality, even engaging in deception for effect, it’s nice to see one of the filmmakers who first acknowledged the ambiguity of the truth in nonfiction film to be at it again and very much on top of his game.

And that skill, that consciousness, is what separates Tabloid from the publications that are on some level its real subject, explored through their coverage of the McKinney story.

The Mormon sex affair took place in the good old days when even Britain’s most voracious journalists wouldn’t overstep reasonable ethical boundaries: “reasonable” strategies included paying big money for scoops, falsifying a photo by superimposing Joyce’s head on a nude model, and hiring their heroine a Rolls Royce to see if she could upstage Joan Collins at a movie premiere (she did).

Yes, not much has changed. If cell phones had existed, they probably would have been hacked. Even if the tabloids of Tabloid used far more classic means, their ends were the same. They gave the public the sensational story it wanted. Joyce McKinney was only too glad, for a time, to be party to this process in exchange for a seat in the spotlight. The truth of the matter may never have surfaced, but it’s not like it mattered.

After all, everyone loves a good story, whether it’s completely true or not. Then and now, facts and ethics can easily be thrown to the wind during the race to capture a jaundiced and fickle public imagination. The thoughtful heft of Errol Morris’ otherwise entertaining Tabloid is that it reminds us of that discouraging fact.