October Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

One startling strand in American music is the maverick or loner: a composer who goes his or her own way, bucking conventions and creating something idiosyncratic and unique.

Every critic can come up with a list of these: Charles Ives, Henry Cowell, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, George Crumb…

And definitely Harry Partch.

Bridge Records has just released vol. 4 in its series of Harry Partch recordings. (Click here to purchase the CD.) Partch died in 1974 at the age of 73. But he left behind a collection of astounding musical instruments that he had invented and hand-based, sometimes from discarded materials (such as large Pyrex jars).

A loose collection of disciples remain devoted to keeping his music alive. That’s part of the paradox of the maverick composer: he or she often ends up being not such a loner after all, because the music speaks to enough players and listeners that they want to get it performed and recorded.

The Wayward: Music of Harry Partch, vol. 4 (click here) is the latest reminder of how vivid and communicative Partch’s music can be. Some of the instruments heard here had to be spruced up or built anew, but the results are as persuasive as the ones on the famous 1969 Columbia Masterworks recording The World of Harry Partch. Two major works come alive with unprecedented vividness and specificity here: Barstow: Eight Hitchhiker Inscriptions from a Highway Railing at Barstow, California and U.S. Highball: A Musical Account of a Transcontinental Hobo Trip. (The Kronos Quartet recording of the latter is far less engaging.)

Also included are San Francisco: A Setting of the Cries of Two Newsboys… , The Letter, and two versions of Ulysses at the Edge [of the World], one including some improvisation, as suggested in the score.

The works evoke loneliness, sorrow, missed connections, colorfully and with puckish humor.

— Ralph P. Locke

Jazz

Chris Wabich is a highly versatile session drummer who has played with pop star Sting, rapper Ludacris, Turkish singer Omar Faruk, steel pan player Boogsie Sharpe, and jazz singer Mark Murphy. On his own session, 1978 (STEEP) (ADW), he’s in a straight-ahead jazz mode, playing a supporting but crucial role in a piano trio that sets its own terms and succeeds in them. Plus, he can swing.

Chris Wabich is a highly versatile session drummer who has played with pop star Sting, rapper Ludacris, Turkish singer Omar Faruk, steel pan player Boogsie Sharpe, and jazz singer Mark Murphy. On his own session, 1978 (STEEP) (ADW), he’s in a straight-ahead jazz mode, playing a supporting but crucial role in a piano trio that sets its own terms and succeeds in them. Plus, he can swing.

Wabich is a fine drummer and composer, but it’s Josh Nelson’s piano that caught my ear. He has a distinctive and appealing touch, more along the lines of Lynne Arriale than Bill Evans or Keith Jarrett. He creates ringing melodic lines on top of softer and simply outlined chords. Nelson can sometimes get a bit New Agey, as on “Magitama (on Slow Shinkansen),” but even there he goes on to some of his most thoughtful melodic explorations.

Bassist Dan Lutz doesn’t stand out, but the music doesn’t ask him to. “Jiang (Sage Ember),” for example, has the bass mixed very deep, contrasting with the bright and high notes of the piano to create a wide sonic field. Add a touch of reverb, and this doesn’t sound anything like a typical piano trio in a club.

Wabich is a master of working the cymbals on the ballads for flow (as Jack DeJohnette knows so well). He knows when to wash, when to keep tempo, when to switch to brushes on the snare. He also treats himself to some tempo shifts and time signature challenges, as on “Ruby on the Old Street/1978,” which goes into 7/8. These are never jarring under the disciplined hands of these musicians.

1978 (STEEP) is a short album at just 40 minutes, and you’ll wish it were longer.

— Allen Michie

Dream Up (Out of Your Head Records), Tomas Fujiwara’s latest album, is a sort of international percussion suite. The tracks generate an alluring variety of primal throbs through compositional approaches that draw on rhythmic beats and associated sounds from around the world. Steve Reich and Max Roach may come to mind, among others, as influences, but Fujiwara is very much cutting his own path through the wide world of percussive sound with the assistance of his diverse quartet.

Dream Up (Out of Your Head Records), Tomas Fujiwara’s latest album, is a sort of international percussion suite. The tracks generate an alluring variety of primal throbs through compositional approaches that draw on rhythmic beats and associated sounds from around the world. Steve Reich and Max Roach may come to mind, among others, as influences, but Fujiwara is very much cutting his own path through the wide world of percussive sound with the assistance of his diverse quartet.

The Boston-born drummer/composer’s Japanese heritage, infused with his US experience, is what spurs on his fellow musicians: Kaoru Watanabe (o-jimedaiko, uchiwadaiko, shimedaiko, and shinobue); New Jersey-born world traveler Tim Keiper (donso ngoni, kamale ngoni, calabash, temple blocks, timbale, djembe, castanets, balafon, found objects) who adds disparate influences (that somehow blend); and jazz poll favorite, Mexico-born Patricia Brennan (vibraphone), who enchants as always.

Intricate, serial syncopations give way to deeper multicultural confluences that are unfailingly intriguing, though listeners may require ethnomusicological analysis to thoroughly unpack what is going on. Or, better yet, you can just sit back and let the music wash over your mind and body.

Interestingly, some of the better cuts on Dream Up add a little welcome frosting on the sonic cake by tossing in non-percussion instruments.

“Recollection of a Dance” and “You Don’t Have to Try” feature Watanabe’s work on shinobue flute and it lightens the atmosphere compellingly. It weaves in and out of the mix, adding grace and, in the latter piece, a poignant peacefulness alongside the pliant strings of Keiper’s ngoni.

— Steve Feeney

Books

A children’s book for adults and kids.

Bill Littlefield, former host of NPR’s Only a Game, Arts Fuse critic, and author of a number of books about sports as well as the novels Prospect and Mercy, brings his talent and love of language to a children’s book, Who Taught That Mouse to Write? And Other Doggerel. Doggerel is “comic verse composed in irregular rhythm.”

Adults and children will enjoy the 31 poems Littlefield has created about animals, insects, fish, and a dragon. They will no doubt find favorites to read over and over. Some of the poems here invite us to consider the peculiarities of an animal like an Octopus: “I dreamed I saw an octopus. We had a conversation. It told me having eight arms was no easy situation.” Other pieces here are laugh-out-loud funny: “A cucaracha what is that? I do not know that word. And should I? It’s not English, right? And isn’t it absurd?” Littlefield also draws from his own childhood experiences. In one poem, he laments trapping fireflies. He raises questions that curious children will like. Would a leopard change his spots? And why does a zebra have stripes?

Whimsical illustrations by Stephen Coren add to the fun. You can’t go wrong with Who Taught That Mouse to Write?

— Ed Meek

Popular Music

Bar Italia’s three members tend to play as though they’re dragging the notes out of their instruments. The opening track, “Fundraiser,” of their fifth album, Some Like It Hot (Matador), goes farthest to counter their reputation for lassitude. A conversation between a man who sounds like a stalker and a woman who can barely remember him, the song is charged with anger. Each time he sings “the way you look, it does me no good/I need you more than I should,” the song’s energy level kicks up a notch.

Elsewhere, Some Like It Hot sounds much less urgent, concentrating on relaxed tempos. Bar Italia maneuver among a small variety of styles — like the folk-tinged ballad “Plastered” — and the mood tends to remain the same. (Pitchfork columnist Kieran Press-Reynolds described them as a “tried-and-true template of ’90s slacker rock.”) The band’s biggest weakness is that so many of their slower songs become bogged down in a sleepy monotony where, regardless of the lyrics, nothing much seems to be at stake.

Each member — Nina Cristante and guitarists Sam Fenton and Jezmi Tarik – serves as a singer/songwriter, so their music encourages a dialogue among their voices, amping up their melancholy. None is a conventionally talented singer but, taken together, they form a unit stronger than their individual parts. (The harmony vocals on “Marble Arch” are off-key, but that lends some warmth to the song.) Fenton’s penchant for swallowing his own lyrics is what hurts the most. He sings as though he’s embarrassed to speak up. “Cowbella,” “Eyepatch,” “I Make My Own Dust,” and “Egghead” all contain some of the liveliness of “Fundraiser,” but the rest of the album fails to capitalize on Bar Italia’s strengths. After five years of recording, they’re still some distance from figuring themselves out.

— Steve Erickson

Modern-day punk raises the question of how rebellious it is to work within a genre that was created in the ’70s. The Nashville band Snooper answers that challenge with a mix of humor, righteous anger, and arty touches. Their second album, Worldwide (Third Man), turns the mosh pit into a food fight, a ringing smartphone present throughout. They tackle the omnipresent traps of consumerism powered by a rapacious corporate culture. The group falls into the micro-genre of egg punk — it is influenced by ’70s Devo. (Snooper lifts one of Devo’s song titles for “Blockhead.”) The Akron band based their identity on an elaborate concept based on the human race reversing evolution and turning into robotic drones; Snooper’s lyrics look upon our times with the same ironic blankness.

Singer Blair Tramel is often drowned out by the rest of Snooper. The album’s rough production incorporates some interesting variations into a set of basic patterns. Synthesizers whoop through the title track. Cowbell snaps come in alongside rhythm guitar on “Guard Dog.” “Blockhead” and “Hologram” verge on hardcore, but the latter opens with keyboards that suggest a cyborg’s nervous breakdown. As much as the band plows full speed ahead, they can pursue a sideways groove as well. “Star *69” offers a warped dance beat. An unusual 92-second cover of the Beatles’ “Come Together” blends punk and reggae.

In performance the band keeps a light tone — they’ve performed onstage with papier mâché puppets — but their lyrics’ remain serious. “Opt Out” complains about the inescapability of modern life’s pitfalls: “this is real life, name your price/you can buy it from a store.” “On Line” lays out a case study of a paranoid woman who’s too scared to leave her home. Tramel becomes absolutely frantic here, howling her way through the chorus. “Star *69” presents the band’s vision at its most cogent and scary: fragments of urgent communication get lost amid the noise of technology.

— Steve Erickson

Film

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei trying on a headpiece in his Rome Opera production of Turandot. Photo: Incipit Film and La Monte Productions

On the one hand, Maxim Derevianko’s documentary Ai Weiwei’s Turandot fits the conventional backstage mold. A plethora of serious challenges arise, some predictable, some surprising. The celebrated Chinese dissident visual artist Ai Weiwei is making his debut as a director of opera (at one point, Ai admits he doesn’t like music all that much). He has chosen to take on Giacomo Puccini’s classic Turandot for the Rome Opera and is determined to revamp its look and storyline to reflect contemporary political struggles, ranging from the refugee crisis and authoritarianism in China, to the arrival of Covid (which interrupted rehearsals, closing the opera house for the first time in 140 years), and the war in Ukraine. (Ukrainian conductor Oksana Lyniv led the 2022 performance, and she is the documentary’s most vibrant human presence.) There’s the usual lineup of informative talking heads, references to unspecified creative disagreements, no sense of critical reaction to the effort, and the customary homages to the power of art, the invaluable rewards of collective effort, and the meticulous dedication of craftspeople. We hear about the obstacles posed by Puccini’s unfinished masterpiece and see that, despite the plague, the opera must go on, and so forth.

But there are compensations aplenty. We don’t hear enough from Ai about how he approached the opera. What we do hear regarding his thinking is enticing. He felt free enough to add a character who, through movement, conveys what the protagonists are feeling. The eye-catching costumes tap into animal/insect motifs and Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement. The set is a map of the world organized — through the use of raised ramps — to signify where the haves and the have-nots live. And there is the example of the courageous Ai himself. We hear about some of his subversive exploits (via footage of his fight for social justice, through art, in China): his work to honor, despite official warnings, the thousands of children who died in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, his imprisonment and beating, and the government’s demolition of his studio. At this point in time, with far too many of our creatives caught like deer in the headlights of a fascist tank, Ai provides a model of the engaged artist — one who believes that “Everything is art. Everything is politics,” and acts on it.

— Bill Marx

Visual Art

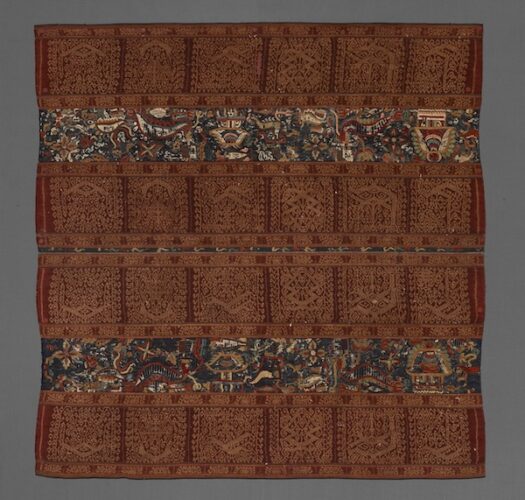

Woman’s Ceremonial Skirt (Tapis), Indonesia, Sumatra, Lampung, 16th–17th century. Cotton and silk; warp-faced plain weave, warp ikat, and embroidery. Photo: courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery.

Its name is Greek. It has 17,508 islands, including the largest island in Asia. It has the fourth largest population (after the United States) and the largest Muslim population in the world. It has been inhabited for at least 54,000 years. Apart from a few popular tourist regions, it is almost unknown to Westerners.

Nusantara: Six Centuries of Indonesian Textile (Nusantara is the original name for the archipelago), now at the Yale University Art Gallery, is one of those exhibitions that opens up a geography of the unknown and unexpected. It is as if every centimeter of the earth had not already been photographed from space. Apart from the famous batiks of Bali, the islands’ traditional textiles are woven, in intricate abstract or geometric figural designs. The galleries are warm and rich; the predominant colors are natural reds.

Easy to reach from the mainland and extensively endowed with natural resources, from nutmeg to iron, the islands were home to hundreds of tribes, kingdoms, and empires, many rich from trade, and with their own languages and textiles. Wall labels explain each island’s traditions, from the monumental designs of Sulawesi, with their scroll motifs and bold diamonds, to the plethora of creatures, based on Japanese designs, on a “waist wrapper” from Java.

Some of these pieces date from the 13th or 14th centuries; their pristine state testifies how precious they were considered. Most of them were meant to be worn in ceremonies, but they are all displayed, old school style, flat in cases or on the wall, as if they were paintings or scrolls. There aren’t even photographs to show how they might look wrapped on a human body. A selection of fascinating objects, like a hornbill sculpture bursting with baroque plums, add context to the cloth.

— Peter Walsh