Book Review: “Matisse in Morocco” — A Masterful Study of One of Most Radical Painters of the 20th Century

By Peter Walsh

Matisse in Morocco is a 35-year labor of love, as meticulously researched as a Ph.D. thesis but without the turgid language, as charmingly composed as the travelogues of Goethe, and with characters worthy of Balzac.

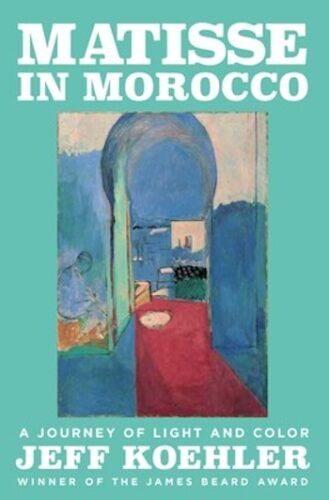

Matisse in Morocco by Jeff Koehler. Pegasus Books, 320 pages, $32

The cover of Jeff Koehler’s new book, Matisse in Morocco is emblazoned, under his name, with the words “WINNER OF THE JAMES BEARD AWARD.” So the reader may be surprised to learn that the text inside does not describe Matisse’s favorite Moroccan dishes, nor does it contain any recipes, or have much to do with food at all. Instead it appears as a 35-year labor of love, as meticulously researched as a Ph.D. thesis but without the turgid language, as charmingly composed as the travelogues of Goethe, and with characters worthy of Balzac.

The cover of Jeff Koehler’s new book, Matisse in Morocco is emblazoned, under his name, with the words “WINNER OF THE JAMES BEARD AWARD.” So the reader may be surprised to learn that the text inside does not describe Matisse’s favorite Moroccan dishes, nor does it contain any recipes, or have much to do with food at all. Instead it appears as a 35-year labor of love, as meticulously researched as a Ph.D. thesis but without the turgid language, as charmingly composed as the travelogues of Goethe, and with characters worthy of Balzac.

Matisse’s paintings, which are Koehler’s real subjects, are so vividly, clearly, and completely described that he gives you not only the glowing colors and the radical compositions but the gallery wall in the museum where they hang, the quality of the light they get there, and the sculpture that stands in front of them. His book is accurately, if a bit cornily, described in his subtitle: A Journey of Light and Color.

Barcelona-based Koehler, it turns out, is the author of a number of cookbooks, including one of Moroccan cuisine, and books on beverage history (coffee and Darjeeling tea). There is nothing in any of this that suggests an interest in art history, much less the ability to write an accomplished monograph on one of the most radical painters of the 20th century. Yet, after decades of gestation (he says he was inspired by his Mom’s gift of the catalogue to the 1990 exhibition, Matisse in Morocco, during his last year at university) he has pulled it off.

In the winter of 1912, Matisse was 42 and in a difficult spot in his career. Years earlier, he had made a huge splash in the 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris with Woman with a Hat, a portrait of his wife, Amelie, with a famous green stripe alongside her nose. This was the exhibition that established the so-called “Fauves” or “wild beasts,” with their vivid, unnatural colors and crude brushwork. Matisse, considered the most outrageous of the bunch, was known as the “Fauve of the Fauves.”

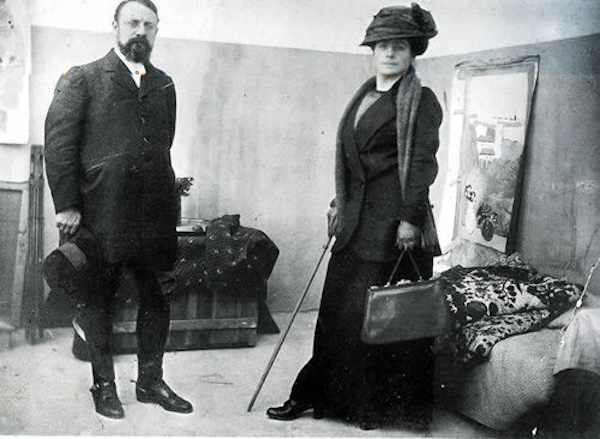

The uproar over the Woman with a Hat attracted the attention of the major American expatriate collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein. They bought the painting and became one of Matisse’s leading patrons. But, by the time he turned 40, the Paris art world had turned a corner. Matisse was no longer considered so avant-garde and a new group of artists, the Cubists, led by Picasso and Braque, were the wave of the future. The Steins stopped buying Matisse’s work and the always wound-up artist, who dressed like a banker or a lawyer and never indulged in the wild behavior considered endemic in Paris art circles, with a wife and young family to support, was a bit adrift.

Henri and Amelie Matisse in Morocco, 1912. Photo: henrimatisse.org

Where he landed was Morocco and more specifically the exotic capital city of Tangiers. This was not exactly an original move. French artists had been taking sojourns to North Africa for generations, ever since France began to eye the region as a capstone to an African empire. Koehler describes Eugene Delacroix’s 1832 trip to North Africa and Tangiers as a parallel to Matisse’s 80 years later. Delacroix traveled as part of an official diplomatic mission and sought, like many jaded Parisians, a view of a more “primitive” and authentic culture. The artist never again returned to Africa, but he gathered enough material on that one trip to fuel the rest of his career, in which scenes based on North African life played a major role.

The start of Matisse’s stay in Tangiers, though, was not auspicious. He arrived during a bout of bad weather that nearly drove him to distraction; he thought of leaving before he had even started. But the skies eventually cleared, revealing to Matisse the mysteriously lucid Moroccan light. He delighted in the local scenes, colors, and smells, making explorations from his hotel that catered to Europeans, finding places to paint, and acquiring a female model (no easy task in a Muslim country). Koehler describes Tangier almost as a life-long native might, providing vivid portraits of Matisse’s haunts, even those which have long disappeared.

Moroccan in Green, Henri Matisse, 1913. Photo: henrimatisse.org

Koehler regards Matisse’s Moroccan stays (there was only one other) as pivotal to his entire career, inspiring many of his greatest paintings, giving him a lasting source of inspiration in the visual impressions he gained and the rugs and Islamic decorative objects he carried back to France. After this first visit, Koehler weaves his narrative back and forth across Matisse’s entire career and its aftermath, always returning to these Moroccan masterpieces. His approach is convincing and easy to follow, even for nonspecialists, helped considerably by his relaxed, unpretentious writing style. In his effort to leave no one behind, Koehler explains every technical and cultural term clearly and translates every foreign quotation and phrase.

Koehler devotes considerable space to Matisse’s mysterious reputation or reputations. Once one of the most mocked and reviled modern artists, he eventually became one of the most admired and beloved, considered, with his sometime rival Picasso, as one of the two greatest artists of the 20th century. Meanwhile, in pre-war Paris, he went from being what Koehler calls “in the wheelhouse guiding Paris’s daring art scene” to, in the eyes of the avant-garde, “passé, a figure of ridicule to be jeered at in public.”

American critics were especially harsh. “It was Matisse who took the first step into the undiscovered land of the ugly,” one of them wrote. The New York Times proclaimed “we may as well say in the first place that his pictures are ugly, that they are coarse, that they are narrow, that to us they are revolting in the humanity.”

Two important collectors of modern art, both of them Russian, thought differently. In the early 20th century, up to World War I, Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, wealthy merchant-industrialists, filled their Moscow palaces with modern art from the West. The two friendly rivals replaced the Steins as Matisse’s most important patrons, particularly for the Morocco paintings. Koehler makes them important figures in his storyline, following their parallel paths through collecting triumphs and family tragedies to their deaths in exile, following the Russian Revolution.

Confiscated by the Soviet government, these two magnificent collections, which contained a large selection of Matisse works, were eventually combined, having survived attempts to have them destroyed as “bourgeois,” into the State Museum of New Western Art, the first in the world of its kind. It was closed under Stalin when Matisse’s art was once again considered “wrongly oriented.” Later the combined collection was divided between the Pushkin and Hermitage Museums.

In exploring the roots of Matisse’s fascination with Morocco, Koehler treats the issue of “Orientalism” with delicacy. In Delacroix and Matisse’s time, Orientalism was a recognized school of art, especially among academic painters, composed of works depicting scenes in the “Orient,” — lands East or south of Western Europe, particularly the Muslim societies of the Middle East and North Africa. There was even a professional organization: the French Society of Orientalist Painters.

Since the publication of Edward Said’s Orientalism in 1978, the term has been politically charged, the start of a long academic discourse that, in part, led to the fiercely moralistic colonialist studies of today. Images of the Orient, it was claimed, were designed to show eastern civilizations as decadent, static, and backward, justifying their colonization by advanced European nations. Orientalism, Said claimed, “enables the political, economic, cultural, and social domination of the West, not just in colonial times, but also in the present.”

The Moroccans, Henri Matisse, 1912. Photo: henrimatisse.org

Matisse was, in fact, working in Morocco at the precise moment France was tightening its strangulation hold on Moroccan independence. But Koehler takes pains to claim that Matisse did not aid and abet this sinister agenda, not even unwittingly. Matisse’s interests, he says, were in light, in color, in atmosphere, in the geometric patterns of the rugs and other Islamic decorative arts he collected, took home to France, and used in compositions for much of the rest of his career.

Matisse was neither a colonialist nor political, Koehler argues. He quotes the critic, Robert Hughes: “Matisse never made a didactic painting or signed a manifesto, and there is scarcely one reference to a political event — let alone an expression of political opinion — to be found anywhere in his writings.” In Morocco, he avoided the standard Orientalist scenes, clichés, and stereotypes. “Creating places of comfort and refuge on the canvas,” Koehler continues, “Matisse configured a world to make people feel good. Even late in life… he continued to make only art that reflected a calming, private domain of pleasure and happiness.”

These arguments are largely convincing, but not entirely. Matisse’s Moroccan canvases are not entirely detached and abstract, separated from Orientalist themes. He took part in the exotic pleasures of the place: the luxurious gardens, scented streets, the elegant arcades, in convivial men’s cafes, the presence of local models in colorful non-Western costumes. In fact, Matisse may have found Tangier in close harmony with his own aesthetic ideals.

“As with Islamic art,” Koehler concludes, “[Matisse’s Moroccan paintings] require no historical background or knowledge of art to enjoy. They are splendid visual gifts… There is pure joy in the two dozen canvases, pure sensual pleasure in simply looking at them. They are, above everything else, feasts for the eye.”

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.