Film Interview: Talking Trash with Annapurna Sriram

By Nicole Veneto

Annapurna Sriram’s Fucktoys is poised for cult greatness among queer cinephiles, filthy femmes, and those of us who find today’s movie landscape frighteningly sex averse.

It’s rare you attend a film festival and come away discovering a brand new director to rank among your favorites. It’s even rarer that you hit it off with her over a shared affinity for camp sensibilities and all things trashy. Annapurna Siram’s Fucktoys is poised for cult greatness among queer cinephiles, filthy femmes, and those of us who find today’s movie landscape frighteningly sex averse. The following is a condensed version of a lengthy interview I did with Sriram after she won the Audience Award for Debut Narrative Feature at the Boston Underground Film Festival.

Fucktoys is currently traveling the festival circuit and seeking distribution. It is scheduled to screen at CAAMFest on May 10th in San Francisco, California and SIFF on May 16th and 17th in Seattle, Washington.

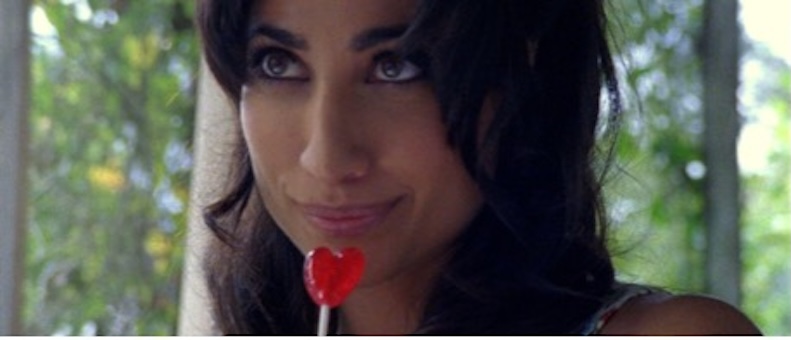

Annapurna Sriram’s AP loves trash in Fucktoys. Photo: Trashtown Pictures

Arts Fuse What does camp mean to you and why are girls (and the gays) the ultimate authority on camp?

Annapurna Sriram: I feel like camp is kind of hard to put into words. It’s a certain kind of irreverent absurdism matched with monochromatic color palettes and irony, like drag and over the top makeup. Camp is this sort of maximalism, but tasteful. And it’s a very hard line to walk. It’s very stressful to set out with the intention to make something camp. We all saw the Met Gala — if you fail, you fail. So we jokingly call Fucktoys neo-camp, or American New Wave revival. The other thing camp is historically is this high end absurdism bringing attention to very real things, but in a way that is so crazy that it’s never saccharine. Maintaining this line of irreverence is key and what’s so fun about it.

I don’t know that many women directors make camp things, whether it’s television or movies geared towards femmes or female presenting people. But I do think there’s something about the little girl or the little boy looking at their mom. There’s this inherent sort of nostalgia, mommy nostalgia. Like looking at your mom or your grandmother doing their makeup or in their bra. There’s something about this idea of femininity or being a woman through this childhood prism that’s matched with whatever era you’re growing up in. [Fucktoys] has a really strong umbilical cord to my childhood; seeing women as a kid, seeing women on billboards. There was this strip club I was obsessed with as a kid, Deja Vu. Seeing the fishnet legs of the women with their heels on the sign that said “100 beautiful girls and three ugly ones.” The child in me was going into this fantasy of being at the club and watching an ugly dancer come out and everyone booing them — that would be an amazing scene in a movie!

I love John Waters. I love Gregg Araki. I love Jim Jarmusch. I love all these directors, but they’re all men. At some level, they’re making movies for other people like them. And I really like this idea of making the girl version, making the movie that has all the fun aesthetics that gets to have all the wacky moments and screwball gonzo comedy. The great costumes that everyone can wear for Halloween. But at the center of [Fucktoys] is femme. It’s a femme story. It’s about girls dealing with men. It’s about trans men. It’s a movie that’s geared towards things that we experience in our lives that when you zoom out, you’re like, “Wait, this is really fucking absurd!”

AP works the back room at the titular strip club. Photo: Trashtown Pictures

AF: What was important to you about depicting sex work on screen, especially at the current moment when sex itself seems to occupy such a contentious place not just in mainstream film, but in film itself?

Sriram: A lot of the stuff in the movie is inspired by real scenes and scenarios. I had experiences in the club, and what people would say to me I would write down on my phone because I thought it was so insane. It was compelling because I was a struggling actor and I was reading all these scripts that I was auditioning for: Law and Order and The Blacklist. All the network television and even indie films. I felt like there was this other life where these much more compelling, idiosyncratic, funny, weird, and interesting scenes existed. So the impetus was more me feeling like there’s more interesting scenes to be written than what I’m reading.

I come from theater, so I was really interested in real, nuanced, and strange scenes. My writing process involves questioning if I’ve seen this scene in a movie before. If the answer is yes, I need to scrap it and then figure out something to reframe it or set it somewhere different so it doesn’t feel redundant. It was an eight year long journey to make the film. So over the course of that time, there was more stuff being made. We had Zola. We had Pleasure. The Girlfriend Experience [television series] was around the same time I was writing. Now we’re in the era of Anora and it just happened to intersect with when I was finally done. There’s a difference between a movie with a famous director who’s known, who’s an indie darling with the support of NEON versus an independent first time filmmaker.

The thing that is really different about my film is that there is a bigger storyline happening. There’s more sisterhood in it, which is reflective of that world. Sex workers are some of the best girlfriends. There’s more of an understanding that there’s community, with inside jokes about what men are like and the expectations of things. The overall discourse is one where I just keep coming back to this feeling that any movie based on a lived experience is going to be different than one based on perceived experience. It’s not to take away the credit or the validity of [Anora], but it’s the difference between an immigrant story being told by an immigrant versus a non-immigrant, or a story about an Indian person being told by a white person versus an Indian person.

My experience with sexuality is that it’s really goofy. It’s really funny. It’s really playful. It’s really absurdist. That’s what is fun. How can we celebrate intimacy and sex and the goofiness of kink? I love kink. Kink is funny. Everything about it, I’m laughing the whole time! I’m having a great time. There’s joy.That was more my intention than anything political. Let’s remember that things are kind of goofy and kinky and fun. That’s actually what kink is.I like the banality of it too. There’s something really funny about the banality of like, “Oh yeah, we can pee on this guy and then later if you want we can get our nails done.”

AP and Danni (Sadie Scott) share a drink at the strip club. Photo: Trashtown Pictures)

AF: You curated a list of films that inspired Fucktoys. Some of the films about sex work are older B-movies, like Angel and Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion. What’s the value of these films in their depictions of sex work as opposed to more dramatic films that are realistic depictions of lived experience?

Sriram: So are some of these eighties movies I have a fetish for. Angel is a perfect example. Like her socks and her heels and her little outfits. There’s something about the younger version of myself seeing [Angel] and loving the whole aesthetic. They’re all shot on film. The color palettes are really exciting. This sexy eighties thriller speaks more to my fetish side. This is why I love Crimes of Passion. I love Lair of the White Worm because I feel like we’re actually getting a taste of the things [Ken Russell] has a fetish for. Things that are just pleasing to the eye. It’s like that strip club, Deja Vu, that I grew up with. There’s something about that. There’s something about Angel. There’s something about Crimes of Passion. Sweet Charity is another example, where I’m seeing this retro-analog creation that aligns with something that feeds my fetish.

This is a really interesting conversation because I think that porn lives very closely in the way that horniness and excitement in your emotional barometer are really close together. Porn and cinema are very close together. The French director Catherine Breillat, who did Fat Girl, Sex is Comedy, Last Summer, when I think about her movies, there’s something about them that’s like kind of hot and it’s fucked up. And I’m into it, you know? Directors get to explore and express these hidden desires, these fetishes. That’s what Sean Baker’s doing. He’s getting to show, “These are the things that I fantasize about. This is how I see it in my fantasy.” I think that that’s connected. It’s maybe just that as a woman, it’s not expected that looking at an eighties sex worker would trigger something in my brain that’s my fetish? But like, it kind of does. I don’t know how to explain it, but that’s part of where my style or my taste comes from.

I can also recognize that [Angel] is more of a B-thriller movie, this isn’t supposed to be depicting a realistic take on this world. I can separate that and that’s okay, I’m happy that they exist. As girls, we’re growing up with all this symbolism and storytelling. How do we make sense of it as adult women? We can celebrate it. We can style things to it. We can make our own versions, which is what Fucktoys is. But in my film, I get to drill down a little bit more into male archetypes and the experience of being a woman with different types of men. These are my experiences that other women might feel are universal.

AP soaks in the sun with The Mechanic (François Arnaud). Photo: Trashtown Pictures

AF: What were some rules and guiding stylistic references you had for Fucktoys?

Sriram: I decided that everything would be pre-millenium, pre-2000. We’re not gonna go into Y2K, we need to set a boundary. I wanted to keep it ’50s to ’90s. It was more drawing on my nostalgia and childhood.I have a lot of French New Wave references and these seventies motorcycle girl references. A really big reference that I didn’t understand until recently is Grease 2 because I grew up with that movie on VHS. I didn’t grow up with Grease on VHS, just Grease 2 for some reason. My mom must have bought it in a bin at a grocery store. Grease 2 is like, “Oh! That’s my aesthetic!” when I watch it.

I wanted to keep my aesthetic timeless and classic so that as the movie aged it wouldn’t become dated. I pulled the color palette from the Rider–Wait [tarot] deck. Looking at that color palette, it really matches a lot of movies from the sixties and seventies: baby blue and red, baby pink and yellow, green. Floral patterns. It was all really aligned with movies like Diva, this 1980s French film. The color palette of Diva is my wet dream. It’s primary colors. I really love it. I don’t love orange or purple. Those are two colors I try not to use. Or even cyan. I tried to keep our blue honest to blue-blue, not cyan-magenta.

I was also really obsessed with all these movies that had all this aesthetic and nostalgia, like Liquid Sky and Jubilee, but lacked narrative sense. So I went through [Fucktoys] scene by scene to have different homages to different films, but then also drawing from this Southern wasteland. In [the film’s lookbook], some of the photos are real photos I took on our scouting, but tying in this sort of whimsy like Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. You watch that movie and it’s like a moving cartoon. That was the thing I really wanted to capture. How can we have this sense of beauty and wonder and whimsy in this dark place of America and capitalism? Things that were inspiring [like] Spun, The Decline of Western Civilization, Gummo, Wild at Heart, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. I have Crimes of Passion in my little strip club. “Hey, Big Spender” from Sweet Charity for color blocking stuff. How can I take my favorite pieces of aesthetics from cinema, of childhood and Americana decay, and mash it up and earn it in the story? That was the thing with a lot of crazy aesthetic movies. They didn’t really have a storyline. So we had to be able to justify why we get to be here.

[The Kenneth Anger-style dream sequence] was very hard for us to do in nailing the layering of color and the color passage of people. I think he must have shot it all on film. Ours did not turn out as beautiful or as crispy as his did. We also shot them on VHS to make it feel like it was part of a movie. So the VHS greenscreen shots were actually much harder to play around with. I was also going off the way that these scenes and these movies feel to me. We get into some Belly and Michael Mann at the end. That was the dream, I guess you can say. My director’s lookbook was the thing I built that was the Bible for the look of [Fucktoys]. This mix of trash and homage.

AF: My last question is more of a marketing suggestion. You should do Odorama cards a’la John Waters’ Polyester.

Sriram: We’ve thought about that! It’s like: dumpster fire, sewage.

AF: Cheap perfume, bad hotel smell, donuts.

Siram: Donuts! Goat manure. Baby goat.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and her podcast on Twitter @MarvelousDeath.