Book Review: Catching Up with Minor White’s Off-Beat Journal

By Trevor Fairbrother

Minor White’s autobiographical undertaking lacks diaristic narrative. There’s too much neurotic navel-gazing too much of the time. Yet it is very appealing as a twisted personal miscellany whose contents range from summaries of sex dreams to snarky letters that were never sent.

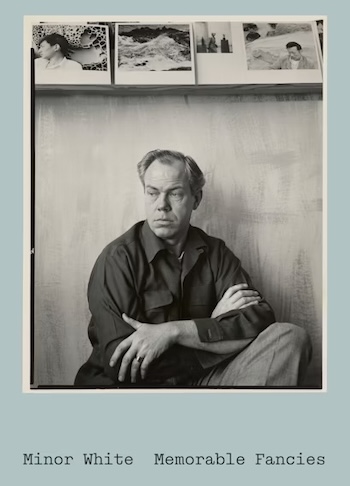

Minor White, Memorable Fancies, edited by Todd Cronan and Peter C. Bunnell; introduction by Todd Cronan; annotations by Andrew Kensett. Published by Princeton University Art Museum, 544 pages, $35.

Minor White (1908-1976) was a vanguard American artist, teacher, and writer. In 1946 he visited artist-photographer Alfred Stieglitz, the high-minded Gilded Age camera guru, and steadily assumed the role of his successor. In 1952, White co-founded Aperture, a magazine to commend and promote photography’s achievements in the realm of fine art. His work explored many subjects: landscapes, architecture, portraits, street scenes, nudes, and abstractions aesthetically crafted as emotional responses to the external realm.

White held academic appointments at the California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco, Rochester Institute of Technology, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in addition to hosting innumerable private workshops. In 1969, as the editor of Aperture Inc., he oversaw the publication of Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations, a grand publication and the only volume devoted to his art in his lifetime. The cover presented Moon and Wall Encrustations, Pultneyville, New York, 1964, a visionary landscape that was likely a detail of the cracks and accretions on a concrete surface.

Princeton University Art Museum acquired White’s archive, personal papers, and photography collection as a bequest in 1976. The donation included the extensive manuscript of Memorable Fancies, an autobiographical undertaking that feels more ad hoc than a methodical operation. Almost 50 years later, the museum has published the off-beat journal “in its entirety for the first time.”

In a prefatory note in the manuscript, White describes Memorable Fancies as a “someday publication.” He took his title from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), the manifesto by the English poet and artist William Blake. Princeton University Press has published White’s text as a handsome 544-page paperback with 100 illustrations of very good quality. The decision to duplicate the unorthodox lay-out of many of the manuscript’s typed pages and handwritten notes underscores the book’s value as a window on White’s individualistic persona. Todd Cronan, a professor of art history at Emory University, contributes a 69-page introductory essay titled “From Expression to Creation: Minor White’s Memorable Fancies.”

While it is conveniently pigeonholed as a personal journal, few are likely to read Memorable Fancies straight out. It lacks diaristic narrative and there’s too much neurotic navel-gazing too much of the time. Yet it is very appealing as a twisted personal miscellany whose contents range from summaries of sex dreams to snarky letters that were never sent. Cronan encapsulates the multifarious complications streaming through the book in one sentence:

No doubt one of the primary attractions (or frustrations) of the book is the sheer diversity of material covered under the banner of photography: from botany to poetry, to psychology, to photographic theory, to letters to friends, to personal encounters with friends and lovers, to itineraries of photographic journeys, to notes for workshops, and, most centrally, to a sustained spiritual journey from Catholicism to Zen Buddhism, to Freudian and Jungian psychology, to Gestalt theory, to Sufism, to Gurdjieffian mysticism.

Equally impactful, as Cronan notes, was White’s predicament as a closeted homosexual. In 1958 the artist inserted the following statement in the early part of his manuscript, alluding to traumatic experiences when he was 18: “I discovered my homo leanings and discovered that the family read my diary in which these discoveries were written. Realizing I would have to live a lie for the rest of my life was a great burden.”

Minor White, Moon and Wall Encrustations, Pultneyville, New York, 1964. Photo: MutualArt

Cronan’s essay for Memorable Fancies examines White’s pattern of taking concepts developed for other creative realms and adapting them as his own for theorizing about photography. He pays particular attention to White’s enthusiasm for Richard Boleslavsky’s 1933 book Acting: The First Six Lessons. The theater director urged his students to develop the craft and discipline needed to steer the emotional response of the audience. This inspired White’s credo: the “final product” of a successful creative photograph is the emotion it arouses in the viewer. (Cronan’s essay abounds in critical theory; for a more lucid image-centered explanation of these arguments I recommend his 2018 lecture “From Expression to Creation: Minor White’s Theater,” available for viewing online.

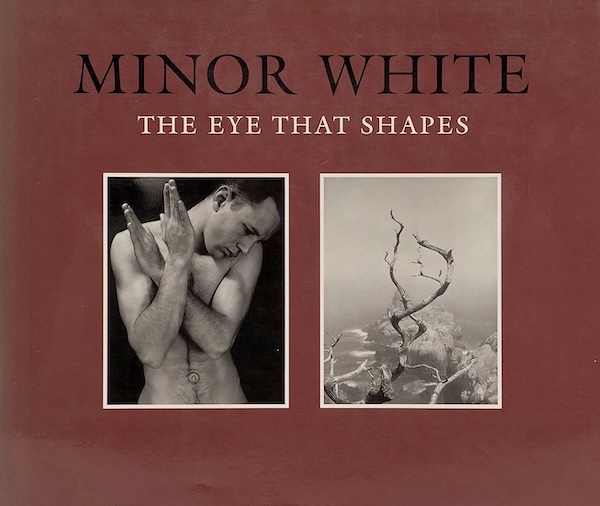

Princeton’s edition of Memorable Fancies fails in one respect: it denies readers a substantive overview of White’s life and career. A biographical timeline would have made the book infinitely more reader-friendly. Cronan alludes to this limitation in an endnote: “For those interested in the biographical dimensions of White’s life I recommend Peter C. Bunnell’s ‘Biographical Chronology’ … in Minor White: The Eye That Shapes.” Bunnell was arguably White’s foremost protégé: his student at RIT then as an early member of the staff at Aperture. He was appointed the director of the Princeton University Art Museum in 1973. The chronology that Bunnell wrote for The Eye That Shapes in 1989 ran over 8,000 words, but it could easily be edited by a quarter: such a text would have been a boon to the current publication.

Let me suggest the problem of glossing over a chronicle of the artist’s career. What was White’s path to photography? He received his first camera as a boy: it was a gift from his grandfather at roughly the time his parents began the first of many separations. He learned more specialized photographic processes as an undergraduate when a class required him to take pictures of algae with a microscope. For a few years White pursued a career as a botanist; then, as it was stalling, he made a determined effort to be a poet. In 1937, a decade after entering college, he opted for photography. After purchasing an Argus C3 35mm camera he moved from Minnesota to Portland, Oregon. He soon found professional work when the Oregon Art Project hired him to photograph historic buildings slated to be demolished. I wish such nuggets of information were easily accessible to readers who find themselves in need of background information as they navigate White’s Memorable Fancies. (Princeton has a website devoted to its Minor White Archive; it includes a biography and a search engine that provides access to thousands of items.)

The cover of Peter C. Bunnell’s 1989 monograph.

White favored secrecy about his sexuality. As a result, he rose to professional prominence and privately paid the price of his discontent and submerged conflicts. The 1976 obituaries published in the Boston Globe and the New York Times evaded this topic by saying White “left no survivors.” Princeton University Art Museum was predictably awkward and tardy about acknowledging White’s sexuality. By the time it did, the AIDS pandemic was ravaging the world. The belated denouement was yoked to Peter C. Bunnell’s landmark exhibition, Minor White: The Eye That Shapes, which debuted at MoMA in April 1989. The cover of the accompanying catalogue pointedly juxtaposed two very different pictures: a view of spiraling wind-sculpted tree branches overlooking the ocean and a half-length study of Tom Murphy posing naked. (In his lifetime White published scarcely any male nudes, and that tender image of Murphy, his student, was unparalleled among them.)

In the 1989 catalogue’s introduction Bunnell stated, “White’s sexuality underlies the whole of the autobiographical statement contained in his work. … His homosexuality caused him to live outside of those kinds of family relationships that usually provide the central focus to one’s life.” When the New York Times reviewed the exhibition at MoMA it commended the curator for acknowledging “the extent of White’s lifelong interest in the male subject.” The critic for the Los Angeles Times, on the other hand, accused the project of “suave curatorial flimflam” that imposed biographical interpretations of White’s private life on his art: “The entire exhibition is anchored on heretofore unshown images of homoerotic nudes whose penises, navels, and shadowed behinds are then linked to progressively more abstract images that resemble them, often vaguely.”

Fast forward to the current decade. 2021 marked the death of Peter C. Bunnell, who, according to the New York Times, “left no immediate survivors.” Malcolm Daniel, an eminent photography curator who took classes with Bunnell, made this observation a year later when Phillips presented four auctions drawn from the estate: “A lot of the literature that [Peter] had in his home had to do with memoirs or fiction dealing with gay subjects. … [He] wanted to see how other people dealt with something that was difficult, particularly for someone of Peter’s generation.” Now, finally, we can congratulate Princeton for doing right by White’s journals. But it is sad, nonetheless, to learn from Cronan’s preface that the museum had a complete transcript in hand by the late ’80s. Bittersweet or not, 2025 is the year when the cat in the orange and black hat coughed up its worrisome hairball. The hairball is big, weird and unpretty, and no two people will see it the same way. I hope the professional biographer who will one day write the first substantive book on White’s life is a person blessed with the wisdom, sophistication, and art historical knowledge to make good use of Memorable Fancies.

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and writer. Last year he reviewed Lisa Volpe’s book America and Other Myths: Photographs by Robert Frank and Todd Webb, 1955 for The Arts Fuse. © 2025