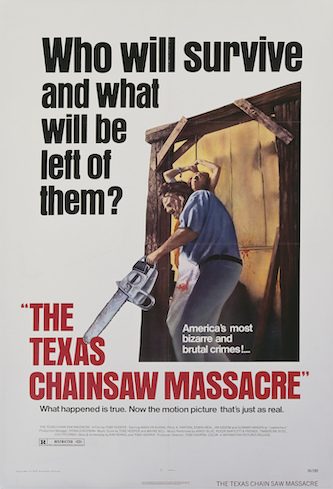

Film Commentary: Looking Sharp, Leatherface! “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” Turns Fifty

By Michael Marano

No 4k DVD, Blu-ray, theatrical digital, or streaming version of the movie improves on the visceral electricity of the original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

It’s iconic: the image of Leatherface, the killer from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, rising to chase that hippie chick played by Marylin Burns through the swampy dawn, chainsaw over his head. It’s on t-shirts, memes, stickers, gew-gaws sold at Spirit Halloween Stores.

But something’s missing from this picture, half a century after that image hit movie screens. Modern iterations of Leatherface are too goddam clear and crisp in this era of 4k restorations and digital clean-ups. Nothing captures the terror Leatherface evoked back in the day than seeing him via a scratched-up print clumsily blown-up to 35mm at a midnight show in a sticky-floored fleapit with shredded seats reeking of cigarette butts. Or, via a second or third generation VHS bootleg of the official Wizard Video or Vestron releases of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre you could nab for four bucks at gas stations next to the “Love Musk” incense and caffeine pills made just south of the DMZ in Korea.

Leatherface pushed the same buttons as would a snuff movie.

Because The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was made with film gear identical to that which showed young people dying as Americans ate dinner while watching Walter Cronkite… back when the tensions of the Generation Gap around the table were as palpable and grating as was the scrape of cutlery through soggy Birds Eye vegetables.

In the ’60s, technical innovations created new possibilities for filmmakers, documentarians, and news crews. Cameras such as the Éclair NPR 16 mm, the Bolex HR 16 camera, the Éclair Cameflex 16/35mm camera (introduced in 1946) and 16mm Eastman Ektachrome filmstock made visual nimbleness and thrift possible. As documentarian Albert Maysles said in the DVD commentary of the 2001 release of Grey Gardens (1975), “All of a sudden, two guys could make a movie.”

Movies made using this gear felt “more real than real”

News footage, documentaries, and low-budget features shot on these formats all shared the same grit and grain, the same shades of black and red. You smelled the pot when you watched concert footage filmed with this gear. Your eyes watered with teargas as you watched reports on campus protests filmed on these formats.

There was a gravitas to these images. You couldn’t question their veracity. Pissant accusations of “Fake News” weren’t conceivable.

A poster for Tobe Hooper’s 1974 horror film ‘The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Photo: Wiki Common

Michael Wadleigh drew on this capacity for verisimilitude to capture the hippie hopefulness of 1969 when he and his fleet of two-person crews shot 120 hours of footage using the Éclair NPR 16 mm for Woodstock. In 1971, also using the Éclair NPR 16 mm, husband and wife filmmakers Alan and Susan Raymond with assistant Tom Goodwin (and under the supervision of producer Craig Gilbert), captured the disintegration of suburban domesticity in the seismically controversial documentary series An American Family. Airing over 12 weeks on PBS in 1973, An American Family told the story of the Loud family of Santa Barbara, detailing t

The flipside of the utopian Woodstock dream was caught months later in another documentary, this one about the Rolling Stones’ 1969 US tour, made by the Maysels’ Brothers’ and Charlotte Zwerin. Gimme Shelter was shot on various types of 16mm Ektachrome. The “more real than real” quality of Gimme Shelter made its climax Zapruder-killshot-shock

Texas Chain Saw Massacre director Hooper and his DP Daniel Pearl shot the violence of Leatherface and his murderous brothers and grandpa on an Éclair NPR using 16-mm film. It evoked “the more real than real.” The film’s violence echoed the carnage seen on daily newscasts via the same type of film, of young people being massacred — in Vietnam, at Kent State, at Altamont, in car accidents, riots, and urban violence. In the ’70s and into the ’80s, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was panic-inducing, with a believability that audiences were programmed to accept as real. Even on those shitty VHS releases of the ’80s, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre exuded a dirty duende — a crudeness the veracity of which could not be denied.

Yes, George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead pushed a lot of the same buttons. But there was a fantastical element to Night of the Living Dead. (But don’t forget Romero cut his teeth editing the exact type of footage we’re talking about for a local Pittsburgh newscast.) As gritty as Night of the Living Dead looks, bodies don’t get up and eat people. Both Night of the Living Dead and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre open in graveyards. But look at the different resonances of their opening scenes. Night of the Living Dead kicks off with a reassuringly unre

It’s not just the use of newsreel film formats and the subversion of the “Horror Movie Opening in a Graveyard” trope that made The Texas Chain Saw Massacre dangerously real to audiences when it was released. Hooper and co-screenwriter Kim Henkel’s use of horoscopes and astrology hit a visceral nerve. In the first two acts of the film, our Scooby Doo-ish van full of teens and early twenty-something protagonists flip through an astrology book and magazine, discussing the Zodiac and destiny and omens. In earlier horror movies, “bad signs” revealed through divinatory magic, like Tarot readings, were a tried-and-true trope. In the era of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the date of your birth truly did determine your likelihood to be blown to shit and left to bleed out in a rice paddy, your death perhaps caught on 16mm, to be seen on Mom and Dad’s 19-inch Zenith.

In 1969 and 1970, the US Selective Service instigated a lottery to determine which young men of military age would be drafted to serve in Vietnam and when. The December 1st, 1969 lottery in particular was based on the cruel randomness of birthdates. As per the ’69 draft, a kid born on September 14 from 1944 to 1950 would be among the very first selected to be shoved head-first into Westmoreland’s Post-Tet meat grinder. Kids born on September 24 from 1944 to 1950, just 10 measly days later, were selected to be the last. Early on in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, one kid reads another’s loaded horoscope: “Travel in the country, long-range plans, and upsetting persons around you could make this a disturbing and unpredictable day. The events in the world are not doing much either to cheer one up.”

Leatherface in action in 1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

A few years after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had been released, mainstream Hollywood came to a reckoning with Vietnam: Coming Home, The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now, Go Tell the Spartans, etc. These were told with professional gloss, real movie stars, clear sound, and pictures. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre had the impact of a television news report, on grainy, goopy film stock, blown up and projected on a giant screen. The editing, the mood, the angles, and the music landed with the cumulative effect of an unending nightmare… one inexplicably shot by a stringer at a news station.

Modern releases of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre — even those transferred to retain the grit and grain of the original prints — can’t capture the medulla-punching effect of the original release. The original mono sound mix of the movie, especially as heard through blown-out movie theater speakers, klanged on the same auditory nerves as did TV news reports. The ’80s VHS releases looked as crappy as segments from The Faces of Death series. Blu-ray, 4k DVD, theatrical digital, and streaming versions of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre dilute and dim the visceral electricity of the original.The image of Leatherface — chainsaw over his head — is diminished to cartoon shorthand.

The more Leatherface is seen with clarity, without grain, without the baggage of the real deaths of young people affixed to it, the more the image of Leatherface as an icon becomes meaningless.

Horror writer, novelist, writing instructor and personal trainer Michael Marano ( www.BluePencilMike.com ) as a teen heard urban legends about pranksters causing stampedes in theaters when they revved up actual chainsaws smuggled in during midnight showings of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. He once had a nice chat and a drink with the late Gunnar Hansen, who originally played Leatherface, and who was a real gent and a hell of a Renaissance Man.