Book Review: The Fascinating Dribs and Drabs of Tennessee Williams’ Genius

This volume of one-act plays may gather up the whiffs and dregs of Tennessee Williams’ achievement, but their flashes of brilliance are valuable reminders of an artist who kept at his craft, come hell and high water, critical as well as popular.

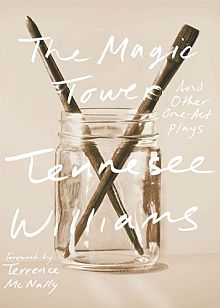

The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays by Tennessee Williams. Foreword by Terrence McNally. New Directions, 286 pages, $16.95.

By Bill Marx

More 100th birthday homages to Tennessee Williams on The Arts Fuse: Joann Green Breuer and Davis Robinson.

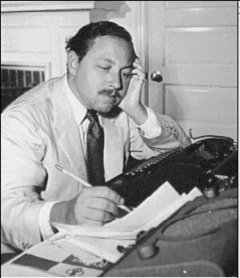

Last month marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of the American playwright Tennessee Williams. The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays, a volume of 15 of his short scripts (many of them previously unpublished), range over his long career as a dramatist, from juvenilia to the late plays whose experimental techniques convinced the critical establishment Williams was a burnt-out case after the 1960s. There are no revelations here, but these pieces—many embarrassing, others fascinating—offer fresh testament to a restless imagination that challenged dramatic business as usual—an alternative that still needs to be defended today.

In other words, despite a full scale reevaluation of Williams going on around the country, myopia remains. In his recent tome entitled Theatre, David Mamet places A Streetcar Named Desire on his list of Great American plays of the twentieth century. So far so good. But he then argues it is the weakest entry on his line-up, which excludes any plays by Eugene O’Neill but includes Boys in the Band and The Women (!), because Streetcar doesn’t offer “a structure of incidents, each of which is an attempt of the hero to advance himself closer to this goal.” It is just that sort of pop-Aristotelian mechanics that Williams rebels against in play after play. His dramas are driven by his sympathy for the battle between two realms of the unheroic: the weak and lost dreamers versus those trapped in uninspiring reality.

This concern with the benighted serves as the through-line for the plays in this volume, an empathy that, in his early texts, comes off as ham-fisted and clumsy. In the pseudo-O’Neill exercise Moony’s Kid Don’t Cry (1936), a working class family flounders on the husband’s childish dream of escaping to another land. Curtains for the Gentlemen (1936), a silly rip-off of Warner Brothers gangster films, offers a smidgen more sympathy than Hollywood to the potential victim of a gang rub-out. In Our Profession (c.1938) attempts a cynical/comic view of contemporary romance, while Every Twenty Minutes (c.1938) is a thin sketch about America’s madness: “We’re all of us inmates of a vast asylum …”

When Williams turns left wing pacifist, the result becomes even more cartoonish: Me, Vashyra (1937) centers on a corrupt international munitions mogul who is destroyed by his guilt-ridden wife and the ghosts of those he helped to kill. Honor the Living (1937) also deals in a heavy-handed fashion with America’s betrayal of its World War I veterans. (“Tell us to get down on our knees and lick your bloody boots, that’s the honor you give us!”) In his excellent notes to the volume, Thomas Keith suggests that the latter text was influenced by a popular anti-war play by Irwin Shaw, but I also see the fingerprint of another Shaw, George Bernard and Major Barbara, in Me, Vashyra’s story of an amoral weapons manufacturer who refuses to take responsibility for his fatal product.

Some of the earlier pieces are more substantial. The Magic Tower (1936) portrays two innocent and poor artistic dreamers (actress and struggling painter) whose idyllic marriage neatly breaks apart after their illusions of love and accomplishment are challenged. That sketch and At Liberty (c. 1939), a terse exchange between a penniless and ill wanna-be actress and her sharply disapproving mother, draw on themes that Williams will explore in later and greater plays, such as The Glass Menagerie.

Speaking of the latter masterpiece, one of the most interesting playets in the volume is The Pretty Trap (c.1944), a shortened version of The Glass Menagerie that uses the Laura and Gentleman Caller meeting for laughs. Interior: Panic (1946) proffers A Streetcar Named Desire in intriguingly skeletal one-act form. In these plays, as well as The Dark Room (c.1939) and The Case of the Crushed Petunias (1941) (Written for Helen Hayes and set in “Primanproper, MA,” the plot focuses on a lonely woman whose repressed iconoclasm is fired up by a fugitive figure of life), we see Williams testing and teasing his primal dramatic situations, experimenting with various tones, structural byways, and verbal colors.

In his astute foreword to the volume, Terrence McNally sees that the later plays are the most promising in terms of future productions, partly because they build on the need to experiment seen in the earlier one-acts. Williams takes up, sometimes with risky abandon, meta-theatrical devices. Kingdom of Earth (1967) is a bruising apocalyptic allegory, with flood waters rising while Southern figures of Thanos and Eros seduce each other. A longer version, entitled The Seven Descents of Myrtle, ran for a short time on Broadway in 1968.

In 2001 I saw a two-act version of Kingdom of Earth at Yale Repertory Theatre. I found its vision to be stylistically strange (an overheated mash-up of Biblical and Gothic) but tantalizing. It would merit a staging, as well as I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark on Sundays (1973) and Some Problems for the Moose Lodge (1980), each of these texts trotting out customary Williams situations but self-consciously manipulating them in surprisingly dreamlike, tragicomic ways.

The late plays also provide proof that Williams accepted his professional plight with sardonic aplomb: . . . Dark on Sundays ends with the nameless Playwright tumbling into the orchestra pit. He climbs out delivering the script’s final line—“”Old cats know how to fall …”

Some of the pieces contained in The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays (The Magic Tower, Every Twenty Minutes, The Pretty Trap, Interior: Panic), received their world premieres a month ago (March 23rd) at the Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival’s centennial tribute to the playwright. So far New England’s homage to Williams at 100 has been pretty disappointing, though the announcement that Beau Jest Moving Theatre will be take on Ten Blocks on Camino Real for its next production is reassuring collaboration that Williams’ unknown plays are worth another look.

Provincetown’s Tennessee Williams Theater Festival will serve up some off-the-beaten path plays in September, including Now the Cats with Jewelled Claws, which I saw staged at Hartford Stage in 2003 as part of the excellent 8 by Tenn.

This volume may gather up the whiffs and dregs of Williams’ achievement, but their flashes of brilliance are valuable reminders of an artist who kept at his craft, come hell and high water, critical as well as popular.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American Plays, David Mamet, Terrence McNally, The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays, tennessee-Williams

Excellent review, Bill.

“It would merit a staging, as well as I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark on Sundays…”

Bill, you might be interested to know that I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark On Sundays was performed as the first of two Tennessee Williams’ world premieres (the second being A Cavalier For Milady) to mark his 100th birthday at The Cock Tavern Theatre in London, March 1-26 this year. (Shelley Lang played “Jane”, Lewis Hayes played “Tye”, Hamish Macdougall directed.) This exclusive production was very successful, featuring on 2 national news programmes, earning a national Critics’ Choice and seven 4-star reviews, and will transfer to London’s West End in September. As the only one of two theatres in the UK commemmorating TW’s 100th birthday, it was a honour to premiere I Never Get Dressed… to such enthusiastic audiences, and we hope to hear of productions in the US very soon.

Nathan Godkin

Press Officer

The Cock Tavern Theatre / King’s Head Theatre

HI Nathan,

I should have checked around more thoroughly. I do hope there’s an American production of this play — The Independent review is quite intriguing. I am also glad to hear about the success of your theater’s recent Edward Bond season … another powerful playwright who has fallen out of critical favor, at least in England. Bond never made much of an impact here, though The American Repertory Theatre staged a terrific production of Olly’s Prison, one of the Bond plays you produced.