Author Interview: Talking to Miss Pat about her “Reggae Music Journey”

By Noah Schaffer

Miss Pat, reggae’s Chinese-Jamaican matriarch, reflects on a life in riddim.

Jamaican popular music has evolved considerably since the ska sounds of the early ’60s, but there has been one constant: The Chin family. In 1958 at Kingston’s tiny Randy’s Record Mart, the family began to record the Skatalites, the rocksteady of Alton Ellis, and the dub explorations of Augustus Pablo. In America, they established the Queens-based VP Records empire, which has ruled during the dancehall era.

Jamaican popular music has evolved considerably since the ska sounds of the early ’60s, but there has been one constant: The Chin family. In 1958 at Kingston’s tiny Randy’s Record Mart, the family began to record the Skatalites, the rocksteady of Alton Ellis, and the dub explorations of Augustus Pablo. In America, they established the Queens-based VP Records empire, which has ruled during the dancehall era.

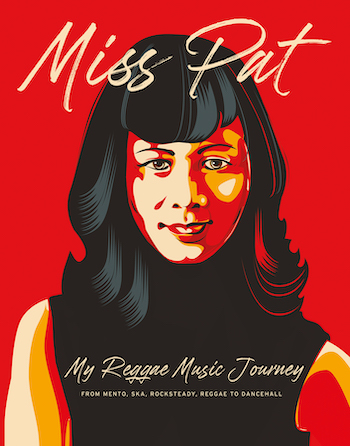

Family matriarch Patricia Chin — known to most as Miss Pat — recently published her memoir, the coffee table-ready Miss Pat: My Reggae Music Journey (VP Records, 212 pages, $55). The volume contains beautifully reproduced photos from reggae’s past and present as well as many warm memories of reggae greats. But Chin also writes unflinchingly about the challenges her family members faced when they began from scratch after they immigrated to America in the late ’70s. The producer talks about her husband Vincent “Randy” Chin’s struggle with the alcoholism that ultimately took his life and how her grandson and VP A&R man Joel Chin was killed in Jamaica.

Recently, Miss Pat spoke with the Arts Fuse about her life in reggae.

Arts Fuse: It’s well-documented how Jamaican music evolved out of the popularity of both R&B and country music on the island. Still, it was surprising to see a photo of your first shop in which records featuring Pat Boone and Rosemary Clooney were on display! Do you remember a song or a moment where you realized that there was a new, more distinctly Jamaican sound arising?

Pat Chin: Yes, that little shop is how we started, when three people came into the store it was full! We used to import a lot of R&B. It was played 24/7 on the radio, because there were just one or two radio stations. Before Jamaican music appeared we used to embrace R&B and jazz and so on. One [major turning point] was when my husband made a record called “Independent, Jamaica” in 1962. We just gotten our independence and there were so many people celebrating. The song was a big hit on the street, so the radio station was forced to play it after a time. Then, in 1964 Jamaica was represented at the World’s Fair in New York: Byron Lee and the Dragonaires brought young Jimmy Cliff, Prince Buster…and the world was given Jamaican music, ska, and rocksteady. And Chris Blackwell recorded “My Boy Lollipop” with Millie Small — in the book there is a photo of her holding up the LP with my husband.

AF: You are of both Chinese and Indian descent. The book mentions that the Chinese-Jamaican community was well represented in the early reggae music industry thanks to your family, Leslie Kong, Justin Yapp, Byron Lee, and several others. Some have compared this presence to the prominence Jews had in the independent R&B record world during the same period. Do you have any thoughts as to what led to the influence of the Jamaican-Chinese community in the Jamaican music industry?

PC: That was a special time and it came about because the Chinese, they put up these little grocery stores, they were called Chiney shops, all around the islands, even in the rural areas where the people were very poor. The Chiney shop owners and the natives became friends: the shops were where people would gather to hear the news, meet their friends, and sell fruit and vegetables. They became community centers. The Chinese children and Black natives become friends. Many of the Chinese people had the money to buy the speaker box [for the sound system or record store]. Quite a few Chinese were musicians, but many of the Jamaicans became record producers, such as Beverley’s and Top Deck. Chin’s Radio Service became the first one to record mento, which came before ska, in the ’50s. But you know all Jamaicans are so gifted when it comes to music. We sing when we’re happy, sad, when we’re working, at funerals…

Miss Pat and Bunny Wailer. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

AF: As a woman in such a male dominated field, did you feel like an outsider? Was working in Jamaica the same as in America?

PC: In Jamaica, there wasn’t a difference between me [at the record store] and the ladies selling on the sidewalks. There was no classification: a woman in a job was no different than a man. But when I came to America in 1977 we did [phone orders] and I remember callers asking me, ‘Can you put a man on the phone? You wouldn’t know what I would want!’ Well, I had already spent 20 years on the counter, both spinning records and talking to musicians, so I knew all the records well. Sometimes we had 15, 20 records come out in a week from different producers. I had to know all the music! Once those callers realized I knew the music, a lot of them were thrown off a lot!

AF: One thing VP Records is really known for is its multi-volume compilations — Strictly the Best, Soca Gold, etc. Can you talk about the first VP compilation and how the concept evolved?

PC: I made the first one in Jamaica in the early ’70s. Every producer had a hit, so I said to myself, ‘why don’t you put all the hits together and we make one LP.’ The name of the first LP in which I put all the producers’ songs on was Hits of the Past” I was able to convince the producers that it would create more success if we combined all the hits together. At first it was difficult to convince them that we should put 10 songs on one LP and share the proceeds — one tenth for everybody. It was a matter of trust; this was a new concept. From there on we went on to do Reggae Gold, then Strictly the Best, then Soca Gold. We have been doing it for decades now: every year we select the songs that were the hits and we put them on one LP.

AF: The book details how you had to adjust during the transition from roots and culture reggae to dancehall. Dancehall lyrics have sparked a lot of debate because of attitudes — slackness, gun lyrics, homophobia. Was there ever a time you were reluctant to release a record because of its content?

PC: Sometimes it bothered me a little. Sometimes, if the lyrics are not pleasant, we do a clean version. So we have two versions, an X-rated one for adults and another one. Sometimes we produce two different CDs, one without the lyrics and one with them. That is how we deal with that problem.. We don’t want to tell the artists they can’t sing what they want. That’s their choice of expression. But we still have to think about kids listening to the songs, so we distribute explicit and clean versions.

Sometimes my granddaughter does the graphics for the CDs and I feel she’s going too far out. Then I say to myself ‘I’m 80 years old, what am I doing telling my 20 year old granddaughter to tone it down?’ It’s the new age, I can’t dictate. [Laughs] It’s a changing time, changing lyrics, changing pictures. I’ve seen discs go from a 78 to a little 45, then came disco, where we had only one side, the other side was blank because we didn’t know what to put on it. Then we decided to add a version where we took out the voice and put riddim on the back. That gave deejays the chance to come in and do their version of the song, do it in different ways. When you take out the voice it means a lot of different things can be done by mixing the music differently. That’s how you got producer Pablo blowing his melodica into the tracks!

Miss Pat and husband Randy Chin at Studio 17 in Jamaica during the early ’60s. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

AF: Yes, the book details far too many artists to discuss, but I’d love to hear your memories of Augustus Pablo.

PC: When I first heard him it was such a beautiful sound. Drum and bass can become so monotonous. His recording of “Java” created a soothing feeling, its Far East sound made for a beautiful combination with drum and bass. It was a change and a beautiful one and it took off, especially in England at first.

AF: To wrap up, the reggae industry is going through another period of change. Some of the bigger stars in recent years, such Chronixx and Koffee, market themselves directly to their fans via social media. In some cases, musicians don’t rely on any label at all. Where do you see reggae going in the future?

PC: Well,the reggae business will continue because every day we have new artists and new producers being born, so reggae will continue whatever way we distribute. And now there are younger people who want to know what happened 50 years ago. Newer artists are always looking backward: maybe they’ll use the same riddim, find a way to couple up with the old music. To assist that I created the Vincent and Pat Foundation, which supports underprivileged younger musicians and preserves the history of Caribbean music through a variety of programs.

Over the past 15 years Noah Schaffer has written about otherwise unheralded musicians from the worlds of gospel, jazz, blues, Latin, African, reggae, Middle Eastern music, klezmer, polka, and far beyond. He has won over 10 awards from the New England Newspaper and Press Association.

Tagged: Miss Pat, My Reggae Music Journey, Noah Schaffer