Visual Arts Commentary: America’s Historical Monuments — Under Reconsideration

By Mark Favermann

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial is the latest product of our heated social/political/cultural debates about America’s memorials and their vision of the country’s past, present, and future.

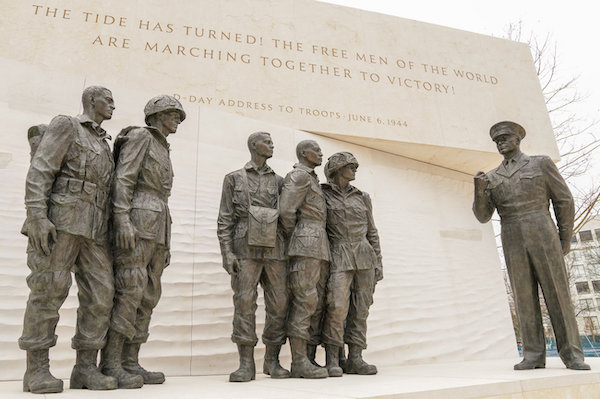

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, DC. (Courtesy Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial Commission.)

At a time when America’s memorials are in crisis, our country’s newest national memorial officially opened in Washington, DC, on September 17, 2020. The Dwight David Eisenhower Memorial opened after almost two decades of dispute: bureaucratic snafus, funding fights, and design and planning conflicts were accompanied by various feuds among members of Congress, the Eisenhower immediate family, and the work’s designer, world-renowned Canadian-born architect Frank Gehry. The piece honors Eisenhower’s legacy as supreme Allied Commander in Europe during World War II as well as his achievements as the 34th President of the United States. The four-acre memorial is located just off the National Mall.

A detailed description of the ins and outs, fits and starts, histrionics and bad antics would be worthy of a multipart HBO miniseries. The army of self-interested players includes segments of governmental agencies, combatants in various congressional playgrounds, family members extolling past-perfect remembrances of their patriarch, and the creative arrogance of a master architect/artist.

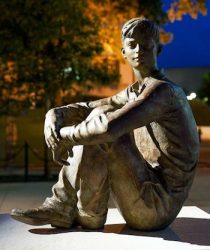

The concept of the memorial was first approved by Congress in 1999. Its eventual cost was $145 million. It was supposed to open in May, but, to the surprise of no one, the ribbon-cutting was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two rather conventional bronze statue vignettes depict scenes from Eisenhower’s WWII military experiences and his presidential career. As a sort of a visual exclamation point, there is also a bronze statue of Eisenhower as a boy sitting with his knees folded to his chest looking lost in thought.

Eisenhower as Kansas Farm Youth. Bronze Sculpture by Sergey Eylanbekov

Somewhat reminiscent of the cliffs of the beaches of Normandy, an imposing 450-foot-wide and 60-foot-tall stainless steel “tapestry” creates an impressionistic background, suggesting what American soldiers might have faced during the 1944 D-Day invasion. The spectacular image is an interpretation of a drawing by Gehry. Though quite abstract during the day, the “tapestry” becomes clearer, and more visually stunning, when it is lit at night.

Though architect Gehry designed the memorial, he collaborated with several artists. Traditional figurative sculptor Sergey Eylanbekov sculpted the rather mundane narrative bronze statues of Eisenhower and his colleagues in various settings. The memorial’s tapestry artist was Tomas Osinski; its inscription artist was Nicholas Waite Benson.

Though the struggles over the Eisenhower Memorial were not laced with charges of racism or misogyny, the rancor and acrimony generated by its design and construction and the continual starts and stops reflects today’s heated social/political/cultural debates about America’s memorials and their vision of our past, present, and future. In the best of circumstances, creating an appropriate memorial is damn hard. Second thoughts, by way of the justification or destruction of memorials and monuments, date back to at least Ancient Egyptian times.

Hatshepsut, daughter of King Thutmose I, assumed the full powers of a pharaoh, becoming ruler of Egypt around 1470 BCE. Among her impressive accomplishments was the exquisite Temple of Hatshepsut. Her stepson Thutmose III followed her and ruled for the next 30 years. Late in his reign, he decreed that all evidence of Hatshepsut’s rule — including the images, statues, and reliefs of her as “king” on the temples and monuments be eradicated. He set out to erase her legacy as a powerful female ruler.

King George III Statue torn down at Bowling Green 1776. Oil painting by William Walcutt. Source: Lafayette College Art Collection.

Greek and later Roman rulers were notorious for destroying or removing statues and monuments dedicated to their rivals or disliked predecessors. Martin Luther and other Protestants were eager to destroy Catholic Church statuary and figurative art during the Reformation. This rebellious movement, in which adherents called for the removal of statues of saints, resonates with today’s antimemorial turbulence. Of course, the toppling of the equestrian King George III statue in the Bowling Green section of New York City in 1776 remains an iconic image of the triumph of the American Revolution and its vision for freedom.

Immediately after the American Civil War, in an effort to reunify the country, venerated Confederate General Robert E. Lee stated publicly (several times) that monuments to the Confederacy’s political leaders and soldiers should not be erected. Yet, during the period of the “Jim Crow Laws” (1880s-1920s) these statues and monuments proliferated throughout the South as a means for whites to consolidate political power by shaping historical memory.

The tearing down of Mussolini and Hitler statues after WWII was a natural response to the lifting of Fascist oppression. Similarly, the destruction of many likenesses and monuments to Lenin, Stalin, Nicolae Ceausescu, et al., as well as other Communist leaders that followed the democratizing of former Communist Eastern Europe and the fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany made sense as inspiring expressions of collective freedom and personal self-worth.

And this practice of demolishing monuments leads us to today and Black Lives Matter, particularly its efforts to erase public homages to Confederate military and political leaders, as well as other notable historical figures, who are judged by their attitudes and actions in regard to racism, slavery, and misogyny. Should we let them be or remove them? Or should we be emphasizing addition rather than subtraction?

For example, women have, ignobly, not often been recognized as heroic figures fit for monuments. Commemorations have usually taken the form of symbols — Blind Justice, Venus, the Little Mermaid, etc. For decades, New York City’s Central Park had only two female monuments: one to Mother Goose, the other to Alice in Wonderland. Now a correction of sorts has come about.

“The Tapestry,” Stainless steel and LED Lights, fabricated by Tomas Osinski

Created by artist Meredith Bergmann, a monument to suffrage pioneers Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton was recently unveiled in Central Park. It was the first statue of nonfictional women ever erected there. The unveiling marked the 100th anniversary of women winning the right to vote in the US in 1920. The piece was initially rejected by the NYC Parks Commission, which insisted “no new statues in Central Park.” Minds changed and kept changing: the initial concept of the monument was attacked by feminist critics as not representing Black women’s contribution to suffrage. There was also outrage expressed at the racist attitudes of both Anthony and Stanton. Eventually, the figure of Sojourner Truth was added to the others. Some feel the addition is artificial, an attempt to curry political favor. Others deem it an appropriate exercise in artistic symbolism.

A useful piece of wisdom to keep in mind as the battles over monuments wage, with no end in sight:

History fades into fable, fact becomes clouded with doubt and controversy; the inscription molders from the tablet: the statue falls from the pedestal. Columns, arches, pyramids, what are they but big heaps of sand; and their epitaphs, but characters written in the dust. — Washington Irving c. 1850

Despite the spell cast by the demands of popular imagination, a monument is not a testament to historical certitude. It should be considered more of a time capsule that reflects the enthusiasms — and limitations — of its makers.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.