Fuse Classical Music Review: A Far Cry — 17 Strings Strong

There is no shortage in this town of chamber music groups trying to carve out a charismatic niche of their own. This seems to have come naturally to this high energy, highly likable ensemble.

By Susan Miron.

Seventeen strings strong, A Far Cry is that rare kind of musical group that appears to do everything right. As Chamber Orchestra in Residence at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, A Far Cry presented the last concert in the museum’s Tapestry Room on December 20. (For the next few months, concerts will be held at the Pozen Center at MassArt). The place was packed, partly because of the rare appearance of a bandoneón and guitar in Los Cuatros Estaciones Porteñas, a tango lover’s dream.

In their third plus year together, this youthful group has received plenty of praise. Although they appear all over the map, the leaderless and conductor-less group has made itself part of the Jamaica Plain and larger Boston community, donating proceeds from their concerts to homeless shelters and partnering with other non-profits such as the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. The famed Orpheus Ensemble in New York began in much the same leaderless way 30 years ago but without the help of the Internet or YouTube.

There is no shortage in this town of chamber music groups trying to carve out a niche of their own to get media attention and audiences. This seems to have come naturally to this high energy, highly likable ensemble. I certainly don’t recall a group with this many players smiling at the sheer joy of music-making or one with such fervent audience and community support.

The program notes themselves were noteworthy, although I had to resort to the internet to find out they are the work of their “mysterious, elusive musicologist-at-large” Kathryn Bacasmot. They began: “This is your shovel. The music is your earth. Dig in.” It went on, gratefully for only one paragraph, in a heady, New Age monologue about obsession, orbiting, gravitational pull, life pulsing in time to the music of the spheres, and circular orbits. Remarkably, she went on to write excellent program notes for each piece. She should let herself be acknowledged. Her notes contributed to the enjoyment of the afternoon.

Cantus in Memorium Benjamin Britten by the well-known, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) opened the program. Pärt yearned to meet Britten personally after he began to appreciate the purity of Britten’s music, but Britten died before this came to pass. To acknowledge the composer’s grief, Cantus opens and closes with silence, executed exquisitely with the 17 players taking visible breaths in unison. A ringing bell hit by a mallet chimes in at intervals. The piece becomes more intense and darker, with the focus shifting to the three cellists and two bass players. Then, after more luscious string playing and more chimes, silence.

Edward Elgar’s (1857–1934) lovely Serenade for Strings, first heard in 1892 , let the strings show off their impressive control over dynamics. These seventeen Criers (as they refer to themselves) knew exactly how to build a crescendo as if they were a quartet. What strikes a listener is how this group, whose members play standing (except for the cellos) and reseat themselves after each piece so no one person gets to hog the limelight as concertmaster, plays as if they’ve been together far more than three or four years. They play with youthful exuberance and professional panache.

The Criers took J. S. Bach’s (1865–1750) much loved Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, BWV 1048, at a brisk tempo. Joined by harpsichordist Matthew Hall, they gave an energetic performance, which I, at least, enjoyed far more than performances on historically “correct” instruments.

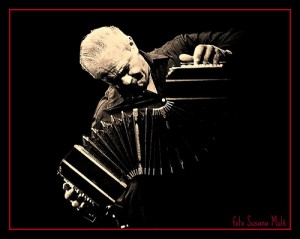

The highlight of the afternoon was Ástor Pantaleón Piazzolla’s (1921–1992) Los Cuatros Estaciones Porteñas, which involved Jason Vieaux, guitar, and Julien Labro playing bandoneón , a smallish, black accordion, which he seemed to be holding on his knee. This was the world premiere of an arrangement for guitar, bandoneón, and strings by the bandoneónist Juilien Labro. Piazzola has had a resurgence of popularity as The Go-To Composer for Tangos (In his tango CD, Yo Yo Ma helped to spread his posthumous fame).

Divided into seasons, starting with summer, Verano Portena: Allegro, these Four Seasons are a workout for all the players, especially Mr. Labro, who was busy hitting his bandoneón , getting all sorts of vibrato out of it, and playing it for all it was worth. The guitar was—and needed to be—miked, and when he finally got some licks, he was very good. Before these sometimes jazzy, sometimes lushly romantic four seasons were done, nearly everyone had had a solo or had done some fun riffs with either the guitar or bandoneón. The Criers handled tempo changes and every other challenge that these pieces presented with flair and a lot of smiling faces. These players clearly love what they do.

The guitar and bandoneón were given an encore piece, “Antonia” from Secret Story by Pat Metheny, which gave Mr. Labro the opportunity to, unexpectedly, blow into his instrument, which sounded like a giant harmonica mixed with a soprano saxophone. It had the atmosphere of a private jam session.

Finally, the slightly exhausted audience was treated to Musica Celestis by Aaron Jay Kernis (b. 1960), a perfect companion piece to the opening Cantus by Pärt. The program notes here get a little spooky—they talk about “the endless interlocking relationships of every key signature by the interval of a 5th, throwing a lasso out into space, catching a little of the infinite within bar lines dotted with notes.” There was great stillness and a hypnotic—yes, scary—atmosphere: the Criers playing very loudly on up-bows and quietly on down-bows, seeming to put their bows down very slowly, then playing a note, another note, until it became a quiet tune.

A Far Cry can play anything and play it really well. They seem to really like each other, and their love of music is palpable. Each of the concertmasters was terrific, moreover they got me to like music I imagined I would heartily dislike.