The Arts on Stamps of the World — December 12

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

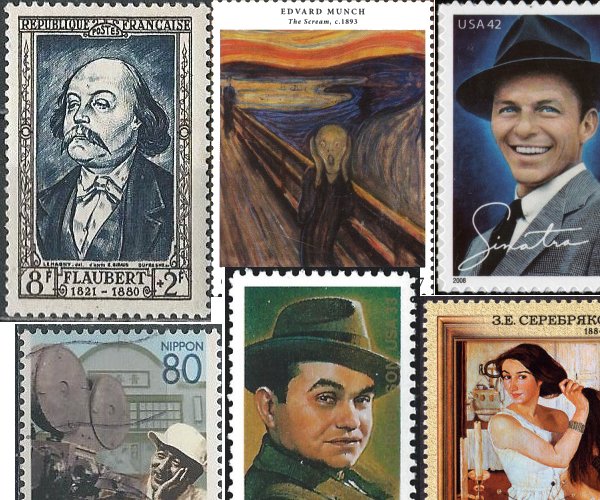

The top names for December 12th are Gustave Flaubert, Edvard Munch, Yasujiro Ozu, Edward G. Robinson, and Frank Sinatra.

The great French writer Gustave Flaubert (1821 – 8 May 1880) is an artist with the rare quality of being almost universally admired. This is due partly to his penchant for agonizing over every comma, and partly due to his unerring instinct to come up with exactly the right comma. Madame Bovary, of course, was initially condemned for portraying as the central character a woman who commits both adultery and suicide, but even sanctimonious critics mostly came around to the realization that the novel was a work of genius. Flaubert never married and never had children, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. Apparently he suffered from one STD or another through much of his life. Wikipedia lists four operas based on his work, the most famous being Massenet’s Hérodiade (1881). In 1863 Mussorgsky had worked on an opera after Salammbô, but left it unfinished (what a shame!), and the masterpiece Madame Bovary was made into an opera by Emmanuel Bondeville (1898–1987) in 1951. I am aware of only a single stamp for the great novelist.

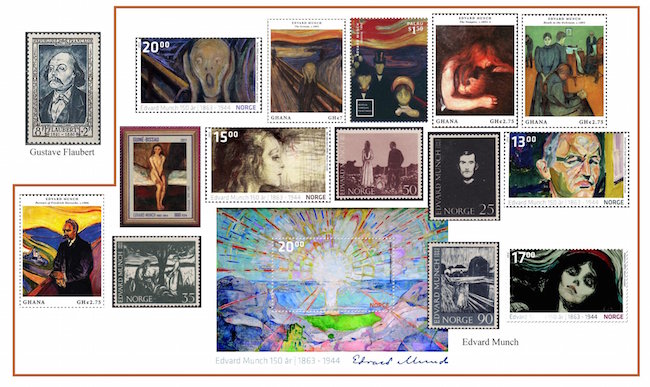

If there is one painting that seems to epitomize the terrifying 20th century, it is The Scream by Edvard Munch (12 December 1863 – 23 January 1944). The essence of the epitome is the focus of the recent Norwegian stamp, one from a set commemorating Munch’s sesquicentennial in 2013, whereas the stamp from Ghana presents (nearly) the complete painting*. Almost as harrowing is a painting that actually bears the title Angst (Anxiety, 1894), seen on a stamp from Palau; and Vampire (1895), on another Ghanaian stamp, is hardly soothing. How pleasant, then, to pass from these states of tension to the relative calm of Death in the Sickroom (version of c1895)! The nude girl in Puberty (1894-95) looks a tad ill at ease, but there are brighter hopes in store with Loneliness (1899) and The Sick Child (1896). (Compare versions of 1885-86 and 1907 if you’re of a mind to visit the sick today.) From the same centennial set of 1963 we have a self-portrait of 1895, but the stamp playfully refrains from giving us the full picture, called Self Portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895). A much later Self-Portrait in Front of the House Wall (1926) is detailed in the more recent Norwegian set. It seems carefree enough, relatively. But then there’s the rather moody 1906 portrait of that jolly harlequin of bonhomie, Friedrich Nietzsche. Two more stamps from the 1963 set give us Fertility (1898) and The Girls on the Bridge (1903). Between them, at last, comes the explosion of rapture, splendor, and warmth of The Sun (1910-11), unless you prefer to see it as an icy and comfortless sun, in which case enjoy the blissful serenity (if that’s what it is) in the face of Madonna (1894).

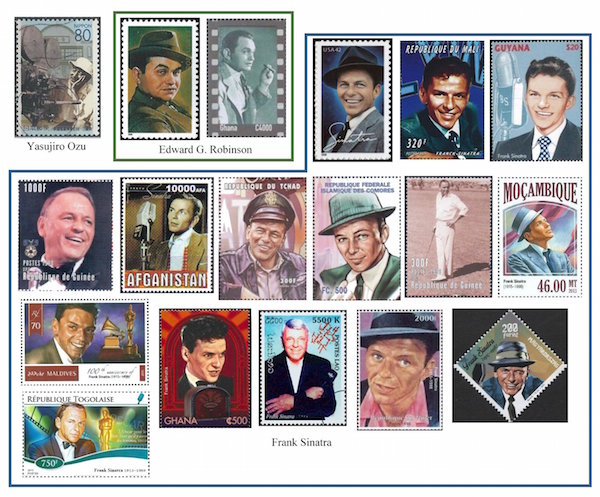

About the great Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu (12 December 1903 – 12 December 1963) Roger Ebert wrote, “From time to time I return to Ozu feeling a need to be calmed and restored.” Perhaps we could use a dose of that after the unsettling canvases of Munch. In childhood Ozu played the truant so that he could watch movies. He decided at thirteen that he wanted to be a director, and at nineteen he was working as an assistant cinematographer. His first film at the helm, a work now lost, was made in 1927. He directed a number of silents, many of them comedies, until his first talkie in 1936. The next year he was drafted and served with the Japanese army in China until 1939. In 1943 he was drafted again, this time to work in film. As a (shirking) functionary of the propaganda machine, Ozu was allowed to observe American movies and was particularly struck by Citizen Kane. After the war he embarked on his series of filmic masterpieces Late Spring (1949), Tokyo Story (1953), and Floating Weeds (1959). His last film, An Autumn Afternoon (1962), contains a line that always stays with me. The “elderly” father is being cared for by his young, selfless daughter, and he urges her to start thinking about her own life. “After all,” he says, “I’m 56. I won’t be around that much longer…”

In the USPS’s series of stamps honoring the top American movie stars, both Edward G. Robinson (in 2000) and Frank Sinatra (in 2008) have been remembered. I also chose a Robinson stamp from a Ghanaian sheet. Sinatra, as you can see, has stamps from many other countries. Edward G. (December 12, 1893 – January 26, 1973) was born Emanuel Goldenberg in Bucharest, Romania. An anti-semitic attack on one of Emanuel’s brothers decided the family to come to America. His stage career began in Yiddish theater and within two years (1915) he was on Broadway. He made only three movies before 1930 but 98 more afterward, coming to fame early on in Little Caesar (1931). A vociferous anti-fascist, Robinson gave over $250,000 to many relief organizations before and during World War II. He was the first movie star to go to Normandy with the USO.

As for Francis Albert Sinatra (December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998), believe it or not, I knew him in my childhood. In the 60s my sister Ellen was a model in Boston and New York, and her roommate knew a lot of people in the entertainment industry. One summer during school vacation when I was visiting with Ellen in her New York apartment, she received a phone call and asked me, “How’d you like to go to California?” We were the guests of Mr. Sinatra at his Palm Springs home, Rancho Mirage, for several days. He was very patient with me. Most of the stamps come from African nations, one notable exception being the Hungarian one, which was issued for the bicentenary year of 2015.

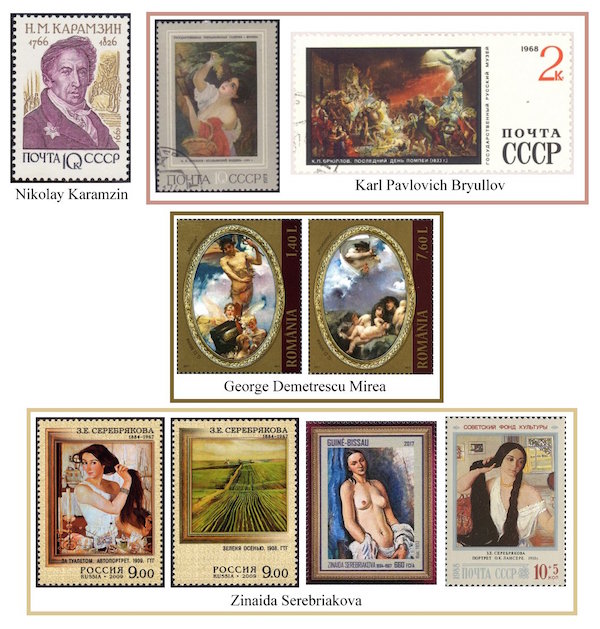

Nikolay Karamzin (12 December [O.S. 1 December] 1766 – 3 June [O.S. 22 May] 1826) was primarily an historian, the author of a twelve-volume History of the Russian State, but he was also a poet, fiction writer, and critic. Karamzin came of the nobility and wrote volumes of his European travels as well as making numerous translations of essays and stories. His style was admired by both Pushkin in the 19th century and Nabokov in the 20th.

We remain in Russia for painter Karl Pavlovich Bryullov (12 December 1799 – 11 June 1852), whose work also found an advocate in Pushkin. Bryullov came of a family of artists of French Huguenot origin. The name was originally Brulleau. Three generations of painting Brulleaus preceded Karl and his brother Alexander, who was just a year older. The brothers went off to Europe on a stipend. While in Italy, Karl painted Italian Midday (1827) and his most famous picture, The Last Day of Pompeii (1833). He returned to Russia to teach at the Imperial Academy in Saint Petersburg from 1836 to 1848, but he ended his days in his beloved Italy.

Born in the year of Bryullov’s death was another Eastern European painter, the Romanian George Demetrescu Mirea (1852 – 12 December 1934). He studied both art and medicine. It was on the recommendation of his teacher in the latter discipline that he took part in the Russo-Turkish War, but he found himself assigned to paint military scenes. The artist Nicolae Grigorescu helped him gain admission to the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. Mirea returned to Romania in 1884 and worked on a number of murals. Soon he took up teaching and eventually was named director of his old alma mater at Bucharest. His pieces Mercury and Prometheus rather look like murals, but are actually framed paintings now housed in the National Bank of Romania.

I absolutely love Zinaida Serebriakova’s Self-Portrait (the leftmost of the four stamps), which looks to me more as if it came from 2009 than 1909, certainly not on account of any “modernist” qualities; it simply seems to me to have a decidedly contemporary “feel”. The artist (12 December [O.S. 30 November] 1884 – 19 September 1967) was born Zinaida Lanceray and like Bryullov came of a prominent family of artists, her grandfather Nicholas Benois an architect, her father Yevgeny Lanceray a sculptor, and her uncle Alexandre Benois one of the founders of the Mir iskusstva art group (and a great-uncle of Peter Ustinov). Her brothers were artists, too. She studied under the great Ilya Repin, in Italy, and in Paris. She married her cousin Boris Serebriakov in 1905 and four years later that enchanting self-portrait, At the Dressing-Table, won the young artist her first public plaudits. The Revolution brought hardship as her husband died of typhus while imprisoned by the Bolsheviks in 1919, and Serebriakova and her four children faced hunger and the possible loss of their home. Her painting House of Cards (1919) poignantly reflects a mother’s anxieties. She was permitted to travel to Paris for a commission in 1924 but was unable or unwilling to return, and in the next four years she could arrange to bring only her two younger children to live with her. She didn’t see the others for decades. Serebriakova became a French citizen in 1947. It was only in 1966 that the Soviet Union allowed her works to be exhibited. The three other stamps show her The Shoots of Autumn Crops (1908), Nude (1932), and Portrait of Olga Konstantinovna Lanceray (Lansere, 1910).

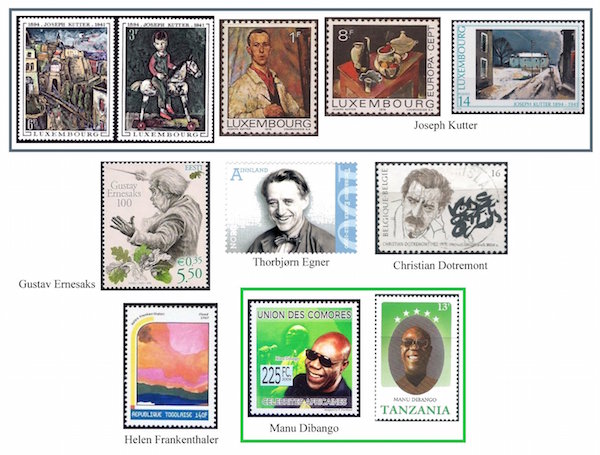

Ten years Serebriakova’s junior, Luxembourgian painter Joseph Kutter (12 December 1894 – 1941) was born to one of the capital city’s first professional photographers. Kutter studied art there and in Strasbourg and Munich. Though he spent much of his life in Germany he was more influenced by French and Belgian Impressionists until finding his own Expressionist style. Even after returning from Munich to Luxembourg in 1924, local negative reaction to his nudes caused him to continue to exhibit in Germany until he was declared “degenerate” in 1933. A few years later Kutter began to experience pain that his doctors couldn’t diagnose. Whatever it was, the illness caused him much suffering and ended his life at age 46. Luxembourg has honored this favorite son with at least five stamps: The Wooden Horse (1937), View of Luxembourg (1937), Self-Portrait (1919), Still Life (1930), and Snow-Covered Landscape.

Estonian composer and choir conductor Gustav Ernesaks (12 December 1908 – 24 January 1993) was an important figure in the Estonian Song Festival tradition. He wrote hundreds of choral songs, but his output is not limited to that genre: there are also five operas, a Symphonic Suite, a Festive Overture for winds, and music for film. One of his songs was the Anthem of the Estonian SSR from 1945 to 1990.

Norwegian children’s author and songwriter Thorbjørn Egner (12 December 1912 – 24 December 1990) is worlds apart from his countryman Edvard Munch. Egner not only wrote songs for children but also plays, he broadcast a children’s radio program in the 1950s, and he illustrated his own books, two of which were made into successful musicals. Perhaps the best known of his books is Karius and Bactus (1949), the story of two “tooth trolls”who live between a little boy’s teeth, a cautionary tale on dental hygiene.

The parents of Belgian painter and poet Christian Dotremont (12 December 1922 – 20 August 1979) were both writers. Dotremont wrote stories from an early age and turned to painting in his later teens, associating with the Surrealists. He married a woman from China and became interested in the art and culture of that country; in later years this influence would be plainly seen in his logograms, one of which is reproduced on the postage stamp. After the war Dotremont split with the Surrealists and co-founded a counter-Surrealist organization, very soon thereafter (1948) joining Asger Jorn in the establishment of the CoBrA (Copenhagen, Brussels, Amsterdam) group.

American abstract expressionist Helen Frankenthaler (December 12, 1928 – December 27, 2011), an important artist in her own right, was married to Robert Motherwell from 1958 to 1971. Ever exploring her art, she turned to printmaking in the early 60s and woodcuts in 1976. Her most celebrated painting is probably Mountains and Sea (1952), but it is Flood (1967) that shows up on the stamp from Togo. A good number of Frankenthaler’s pieces can be seen at the MFA.

Finally today we salute Manu Dibango (born 12 December 1933), a Cameroonian musician in a style combining jazz, funk, and the traditional music of his homeland. Born Emmanuel N’Djoké Dibango, he plays saxophone and vibraphone and is a composer who has released dozens of albums since his first in 1968. He was named a UNESCO Artist for Peace in 2004.

*Apart from the lithographs, there are actually four versions of this iconic canvas, two pastels from 1893 and 1895 and two paintings from 1893 and 1910. Both the paintings were stolen (1994 and 2004) and recovered.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.

Yowza! What a day! And “that jolly harlequin of bonhomie” was icing on the proverbial cake. GOOD one!

🙂