Classical Music Feature: Listening to a Legend

Alfred Brendel was the first pianist to record all of Beethoven’s piano music in the 1960s and made many world tours with the 32 sonatas, which seemed like old, close friends. At times he would simply play a snippet here and there to illustrate a point, yet never long enough to satisfy this listener. I would have been happy to just hear him continue playing.

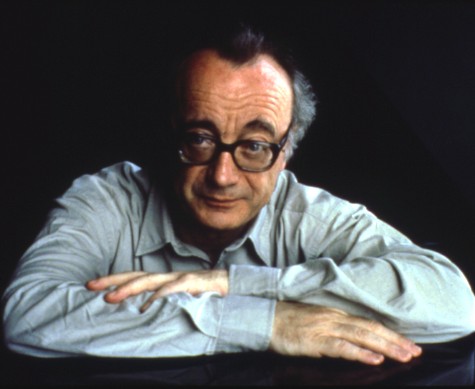

Writer, poet, pianist, and painter Alfred Brendel—he has the precious ability to understand musical humor.

By Susan Miron.

A line of many hundreds of ticket holders—all the free tickets were gone weeks ago—stood patiently in line, snaked around Harvard University’s Paine Hall Thursday afternoon (October 13) awaiting musical illumination from revered, recently retired pianist Alfred Brendel. The master’s lecture demonstration, entitled “Musical Character in Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas” attracted a distinguished audience of several generations of prominent musicians and music lovers. All had a sense of occasion. There was little coughing; everyone was too busy hanging on his every word and note.

Dressed casually, Mr. Brendel was introduced by Harvard’s own very distinguished pianist and scholar Robert Levin, one not given to fawning over anyone short of Mozart. Mr. Levin recalled listening at an early age to Brendel recordings and heaped praise on Mr. Brendel, a quintessentially Viennese “apostle of musical probity,” who had devoted a career to Mozart, Beethoven, Haydn, and Schubert, who made such a strong case for Franz Liszt that musicians had to “revisit” his music. Perhaps most importantly to very serious Mr. Levin, Mr. Brendel had the ability to understand musical humor.

Brendel devoted most of the hour and a quarter lecture demonstration to talking and then providing musical examples from all periods of the Beethoven sonatas. Mr. Brendel was the first pianist to record all of Beethoven’s piano music in the 1960s and made many world tours with the 32 sonatas, which seemed like old, close friends. At times he would simply play a snippet here and there to illustrate a point, yet never long enough to satisfy this listener. I would have been happy to just hear him continue playing.

Brendel retired when he was still at the top of his game; he certainly sounded as great as ever on Thursday. His piano playing reflects a tremendous musical intelligence, of knowing what repertoire speaks to him and sticking with it throughout a lifetime. His lecture was aimed at a musically educated audience and might have been quite confusing —if not dry—to those who, at the very least, didn’t know Beethoven’s piano sonatas. He spoke to the huge audience as if he were giving a private piano lesson. His voice was quiet as he read from a script held on a music stand near the piano. The drama was saved for the playing.

He pointed out that everything is introduced in the first few measures in many sonatas. Each Beethoven sonata, he explained, is a landscape unfolding before the musical eye. Each has its tempo determined by the music’s character. Each has its own mood and perspective.

Brendel is also a poet and painter whose essays appear in The New York Review of Books. Although his manner and voice was professorial, he would casually drop the most poetic descriptions of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. There was the “transparent opalescence” of the Waldstein, the middle section of the Pastorale Sonata “wholly untouched by melancholy,” fugues embedded “like the eye of a cyclone.” Of the late, great Opus 109, he mentioned how the first movement “hovers a few inches about the ground,” while the second movement “scrapes into the earth.” “It helps to be alert to the nuances of language,” he insisted, as if this were something one doesn’t spend a lifetime trying to do.

I suspect this lecture might end up, like much of Brendel’s writing, in print. But without his beautiful musical illustrations, it will lack the sense of occasion and of musical magic enjoyed by those lucky enough to get seats Thursday afternoon.

Tagged: Alfred Brendel, Beethoven, Classical Music, Sonatas, piano