Fuse Book Review: Why Do American Critics Fear Being Critical?

A symptom of our times: two books by self-described critics that aren’t particularly critical. Informed, lucid, thoughtful, and explanatory, yes—strongly evaluative, no.

Beautiful & Pointless: A Guide to Modern Poetry by David Orr. HarperCollins, 200 pages, $25.99.

Except When I Write: Reflections of a Recovering Critic by Arthur Krystal. Oxford University Press, 193 pages, $24.95.

By Bill Marx.

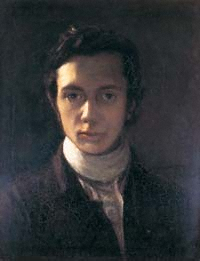

A symptom of our cultural times: two books by self-described critics that aren’t particularly critical. Informed, lucid, thoughtful, and explanatory, yes—strongly evaluative, no. Orr is the poetry columnist for The New York Times Book Review; Krystal is a loose cannon who publishes in Harpers, The New Yorker, and other tony publications. In Beautiful & Pointless, Orr offers readers a demystifying glimpse into the hothouse world of professional American poetry. He argues that a self-defeating vision of difficulty and idealization—often generated by the poets themselves—turns casual readers away from taking a look at contemporary verse. Krystal’s smorgasbord of his recent essay-reviews features an invigorating piece on a recent biography of 19th-century, English critical firebrand William Hazlitt. Too bad neither Orr or Krystal have that kind of fire in their bellies.

To be fair, Orr is nothing if not dryly feisty, sardonically aware of the PR problem that besets contemporary poetry. In a culture dedicated to ease of access, verse is saddled with a reputation for being demanding: “If you’re a casual reader, then, it’s easy to feel that your response to the art is somehow wrong, that you’re either insufficiently smart or insufficiently soulful.” Readers need to relax, he submits, readjust their exceptions and simply accept what pleasure and illumination comes with reading a poem. Approach reading contemporary poetry, he suggests, as if you are going on vacation to a country you hadn’t visited before, such as Belgium, “all you need is a little patience and the motivation to book your tickets.” Orr plays the down-to-earth, preparatory tour guide, giving us the lay of the American verse-land, reporting on what the natives are chatting and arguing about, warning us not to take the knife fights, prophetic airs, and political grandstanding too seriously.

Because Orr picks the genially civilized Belgium you know TNYBR is sponsoring the tour. Countries with mountains to climb or trouble spots to negotiate would suggest too much effort. It is gentility in defense of common sense that mitigates against critical bite in Beautiful & Pointless. Not that Orr doesn’t score points in his overview of endangered planet poetry. In such chapters as “The Personal,” “The Political,” “Ambition,” and “The Fishbowl,” he amusingly notes the conflicts of interest, the preening, the mania for ambition, and the swamp of poetry criticism that ladles out unctuous puff and/or arcane academic blather. Along the way, he makes some revealing points about a damaging set-up geared to isolate poetry from the broader culture: perceptions of marginalization fuel a hyperbolic rhetoric of significance that salves the defensive egos of poets but frightens off causal readers who just want to enjoy what they read.

Orr charts some of the problems in the system, but he doesn’t offer any suggestions to reform it. He tells us that poets should be part of academia but not a part of it at the same time—how does a poet pull that off? Most versifiers are content to be cogs rolling toward tenure in the diploma mill. As for the flexibility of modern poetic form, Orr posits the interesting concept of “Resemblance”: “A form isn’t a schematic, but a practice—and in this sense, form can be compared to a game . . .” What this seems to mean is that Orr approves of what Robert Frost disparagingly opined about free verse—it is like playing tennis without a net. For Orr, a resemblance to the age-old rules is enough. An intriguing approach, but he doesn’t deal with the possibility of the abuse of freedom—Is it water polo without a pool? Baseball without any bases?

For me, there is a chapter missing—“Criticism.” Poets often talk about reviews (both of their own books or notices of their competitors) or the lack of them. Orr points out that poet August Kleinzahler is disliked by the poetry community for his attacks on versifiers who embrace the comforts of academe, but a tough poetry critic such as William Logan earns considerable homicidal contempt as well. Orr is careful not to deal with the issue of mediocre verse, so when late in the book he admits that contemporary poetry is “often not very good at all,” the judgment comes as a surprise. We hadn’t heard about the time wasters. Don’t guide books tell us, even in a land as civilized as Belgium, what areas to stay away from (at least after midnight) and why?

The key passage in Beautiful & Pointless comes when Orr explains what turned him on to poetry. He “grew up thinking of poetry as something to be endured in school with the polite determination we typically reserve for tuba recitals and conversations with very old people.” One day he picks up a volume of Philip Larkin’s The Whitsum Weddings and he falls in love with the poems. Orr doesn’t admit it, but one of the reasons he became hooked was that the poetry was good, in contrast to the verse that had left him cold. His appetite for more literary value, and a curiosity about understanding how this quality was achieved, drove him to read more of Larkin’s poetry and then to study up on the poet.

Orr’s adoration is inevitably mixed with the urge to evaluate, to compare and contrast, to pursue his interest about what separates the sheep from the goats. It is the intellectual component of his affection for poetry, perhaps because it means having to work for the sake of increasing pleasure (which is anathema to America consumers, who like their literary leisure time activities to sound hard but come easy), that he represses.

Criticism is a primal appetite, and when it comes to the arts we all become critics once we become passionate about our desires. The question is whether we ever develop the chops of our inner reviewer or stick to flinging our thumbs up or down. To his credit, Orr wants us to fall in love with poetry: “It needs to have been read, and thought about, and excessively praised, and excessively scorned, and quoted in melodramatic fashion, and misremembered at dinner parties.” But that kind of fervor, resembling the knowledgeable and compulsive mania of the sports fan, comes when you believe the game is far more than just beautiful and pointless.

On the other hand, Except When I Write reflects the varied cultural interests of an intellectual son-of-a-gun. Krystal’s essays and reviews are unfailingly lucid and balanced-to-a-T, as is customary for this writer (I would highly recommend this and his other two essay collections). This time around his subjects range from the dearth of contemporary aphorisms and a warm portrait of quirky omni-thinker Jacques Barzun to a generous and judicious calibration of F Scott Fitzgerald’s lackadaisical career in Hollywood (“Fitzgerald’s scripts were hobbled by the same quality that lifted his fiction above the superficial: the complicated nature of his mind”).

Yet the volume’s sub-title is a puzzler: “Reflections of a Recovering Critic.” What kind of picky condition is he attempting to get over? Few of the pieces contain much judgmental kick — the closest is when Krystal thinks the author of a book exploring the night “doesn’t know when to hold back.” Krystal knows how to do that easily, perhaps too easily. In fact, there’s an air of chumminess rather than heady confrontation in a number of these pieces: a highly admiring review of Morris Dickstein’s Feasting with Panthers is matched by a blurb from Dickstein extolling Krystal’s earlier volume Agitations: Essays on Life and Literature. Jacques Barzun supplies a magisterial effusion of praise for another Krystal volume.

And when the essayist tries to play the curmudgeon it comes off as rusty. At one point, Krystal attempts to dismiss Edmund Wilson as an out-of-touch intellectual who rejoiced at the crash during the 1930’s. He cites this quotation from Wilson: “One couldn’t help but be exhilarated at the sudden unexpected collapse of that stupid gigantic fraud. It gave us a new sense of freedom; and it gave us a new sense of power to find ourselves carrying on while the bankers, for a change, were taking a beating.” This perspective takes on considerable ironic resonance at a time when young people, seeing no jobs in their future, march on Wall Street. Aside from that, Wilson covered worker agitation and strikes for The New Republic and other publications. (Check out “Frank Feeney’s Coal Diggers” in The American Earthquake.) Let’s see Krystal hit the barricades before he dismisses a writer articulating the excitement of the jobless when they see the high and mighty feel some pain.

You can’t help but wince at the fainthearted fare of Except When I Write in the light of a critic Krystal admires, William Hazlitt, a red hot volcano of cultural contention. Praising Duncan Wu’s recent biography of Hazlitt, Krystal notes the writer’s transformation from a thinker into something more: “the pedant gave way to the polemicist, the Critic to the critic-reviewer, and culture became a topic of public discussion –- and dissension. In fact, literary journalism, in its first incarnation, was probably as intense as it would ever become.” True — interesting that another great hell hound literary critic from the 19th century, Edgar Allan Poe, makes an appearance in the book only via an interesting piece on how he fathered the detective story.

Krystal is praised by some as “making a vigorous case for the virtues of old-fashioned literary criticism.” At times I am not quite sure what kind of ‘old-fashioned’ criticism he is fighting for. Krystal knows better than most that the history of criticism isn’t just made up of genteel writers, albeit informative and lucid, who wouldn’t rile your Aunt Minnie with their ideas or prose. Others carried on the blazing torch of dissension lit by Hazlitt and Poe — H. L. Mencken and Dwight Macdonald among them. It is that tradition of intellectual intensity that needs to be recovered, not recovered from.

Tagged: Arthur Krystal, Beautiful & Pointless, David Orr, Except When I Write, criticism