Book Review: Director Edgar G. Ulmer — Hollywood’s Master of the Eclectic Led a Doozy of a Life

In recounting the filmmaker’s amazing career, Isenberg moves easily between describing the drama going on behind the scenes and analyzing the provocative work that Ulmer put on screen. This is an invaluable volume that can and should be read in conjunction with one’s own Ulmer movie marathon.

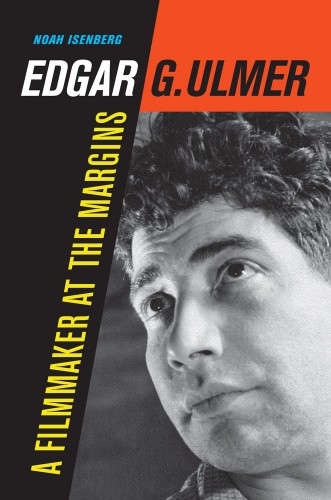

Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins, by Noah Isenberg. University of California Press, 384 pages, $34.95.

By Betsy Sherman

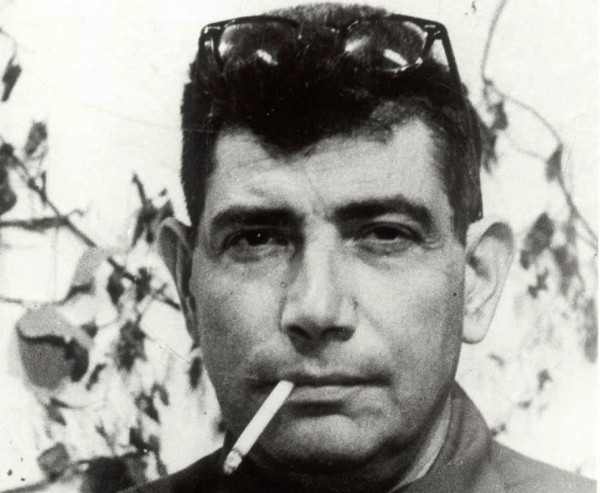

Once upon a time, fans of director Edgar G. Ulmer (1904-1972) had to be happy with crumbs. There weren’t many resources about the man behind the eclectic group of films that, in a weird and wonderful way, mixed a highbrow European sensibility in with the lowdown charms of the Hollywood genre picture. In English (of course Ulmer was appreciated in France), there was chiefly the marathon interview conducted in 1970 by Peter Bogdanovich, which has been published in various incarnations. In Bogdanovich’s 1997 Who the Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors, Ulmer’s fantastical tale of performing alchemy with rock-bottom budgets, schedules measured in days rather than months, and actors that weren’t box-office draws is sandwiched between interviews with big-studio big shots Hitchcock and Preminger. It eventually came to light that some of Ulmer’s claims about having been part of many of the seminal events in the history of cinema were, um, exaggerated, but even so, it was a doozy of a life.

In the past few years, however, there’s been considerable activity on the Ulmer front. Besides the release on DVD of several (but not enough!) of his nearly forty features, there have been collections of essays about his films, the documentary Edgar G. Ulmer: The Man Off-Screen (which contains audio clips from, and affectionately debunks aspects of, the Bogdanovich interview), and Stefan Grissemann’s Mann im Schatten: Der Filmemacher Edgar G. Ulmer (which I bought just in case, you know, I ever learn German). Now, finally, comes the publication of Noah Isenberg’s decade-in-the-making biography Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins (University of California Press). With sober intrepidness, Isenberg tethers down to earth some of the more wild claims made by and about his subject. In recounting the filmmaker’s amazing career, he moves easily between describing the drama going on behind the scenes and analyzing the provocative work that Ulmer put on screen. This is an invaluable volume that can and should be read in conjunction with one’s own Ulmer movie marathon.

Ulmer’s career is initially noteworthy because of its breadth: ranging in time from the late ’20s to the early ’60s, taking place in various geographical locations around North America and Europe, and spanning storylines to include the genres of horror, melodrama, science fiction, film noir and semi-documentary. There’s depth here as well: the director’s best work stands up to multiple viewings. His signature piece is Detour (1945), a harbinger of post-war films noirs to come, in which a piano player relates in voice-over, with increasing desperation, the sequence of twisted events that unfolded as he hitchhiked from New York to California to rejoin his fiancée (Isenberg wrote a monograph on Detour for the British Film Institute’s Film Classics series). The movie is compact, potent, and strangely moving — words that can be used to describe all my Ulmer favorites, such as the Karloff-Lugosi pairing The Black Cat (1934), the contemporary dramas Tomorrow We Live (1942) and Ruthless (1948), the historical thriller Bluebeard (1944), the science fiction tale The Man from Planet X (1951), the Western The Naked Dawn (1955) and the ensemble parable The Cavern (1964). Hell, I’d even use those words for Ulmer’s 1933 educational film about syphilis, Damaged Lives.

Isenberg places Ulmer’s back-story in its historical and cultural context. The Ulmers, a family of secular, assimilated Jews, moved to Vienna not long after Edgar’s birth in the Moravian town of Olmutz (now part of the Czech Republic). For the rest of his life, Ulmer would romanticize the Vienna of his youth. Tragedy struck when Edgar’s father died in World War I, as part of the Austro-Hungarian army (the most obvious of several instances of father-deprived children in Ulmer’s work comes in Strange Illusion, his modern adaptation of Hamlet). Towards the end of the war, Edgar and his sister were sent to live in Sweden (exile is another overarching theme in his films). Details about Ulmer’s education are sketchy, but he developed a passion for theater, and moved to Berlin to study with the world-famous Max Reinhardt. In 1924, at age 19, he traveled with Reinhardt’s company to New York to help mount the production of The Miracle.

During next five years Ulmer made a thrilling entry into the motion picture field, first in the art department at Universal in Hollywood (founder and fellow émigré Carl Laemmle was in the practice of hiring promising young landesmen like Ulmer and William Wyler), then as a protégé of the great F.W. Murnau, working in Germany on The Last Laugh and returning to California for Sunrise. Back in Germany, Ulmer co-created the legendary Menschen am Sonntag/People on Sunday (1930), a naturalistic day-in-the-life look at young Berliners, featuring a cast of non-professionals. Ulmer co-directed with Robert Siodmak from a script by Billy Wilder, with camera work by Fred Zinnemann.

Four years later, Ulmer was poised to direct his first American feature at Universal. The Black Cat, the darkest and arguably richest entry in the studio’s early ’30s horror cycle, could have been its director’s entry into the big time, except for what transpired behind the camera. Ulmer incurred the wrath of the entire Laemmle family: he fell in love with Shirley Kassler Alexander, wife of Carl’s favorite nephew. They divorced their respective spouses and married, and were effectively blacklisted by the close-knit Hollywood film industry.

Consequently, the story of Ulmer’s career is also the story of a couple, with script supervisor Shirley a crucial collaborator on Edgar’s film shoots (since Shirley’s death in 2000, the family’s keeper of the flame is daughter Arianné Ulmer Cipes, who runs the Edgar G. Ulmer Preservation Corporation). They resettled in Shirley’s hometown, New York. In the chapter “Songs of Exile,” Isenberg illuminates the director’s work in the late ’30s, when he specialized in films aimed at ethnic minority markets. He made two Ukrainian-language musicals, four superb Yiddish-language features using talent from New York’s Yiddish stage (these films have been restored by the National Center for Jewish Film), and Moon Over Harlem, a drama with an all-black cast.

During World War II, the Ulmers returned to the West Coast and commenced the “King of the B’s” period with which Edgar would become most often identified. Under contract at the low-rent Producers Releasing Corporation, he had creative freedom that he wouldn’t have had at the major studios, but had to get by with the “Poverty Row” studio’s inferior technical resources and lesser marketing clout. His fellow alchemists at PRC included Hungarian composer Leo Erdody, who shared Ulmer’s passion for classical music, and German cinematographer Eugen Schufftan. The latter was, writes Isenberg, “known … for a deeply refined, painterly approach to shadow and light.” The quickie films they made together rose above the ordinary, to say the least.

The chapter “Independence Days” charts Ulmer’s postwar work as a freelancer, during which he crossed the Atlantic countless times, making films in Italy, Spain (where he made the flop comedy Babes in Bagdad, featuring Gypsy Rose Lee), Germany, New York (where he realized his pet project, Carnegie Hall), Texas, Mexico, and Los Angeles. This is the period for which Isenberg had a wealth of correspondence upon which to draw, not only among Ulmer, his wife and his daughter, but also between Ulmer and his agent Ilse Lahn. The letters show the sometimes hot-tempered artist repeatedly embarking on projects with high hopes, only to end up venting about the compromises he’s been forced to make. Ulmer’s last film, The Cavern, was shot in Yugoslavia. He suffered a series of strokes that prevented him from following through on his many dream projects.

A by-product of the director’s versatility is that Ulmer scholarship has tended towards a blind-men-and-the-elephant scenario: genre specialists will become excited about those films closest to their reach, be they science fiction, hard-boiled pulp, or even the nudie movie (Ulmer dabbled with The Naked Venus). I have some quibbles with Isenberg about his treatment of individual films — for example, I wish he hadn’t merely passed over The Perjurer (1956), a movie Ulmer produced in Germany that has thematic links with his directorial canon. But this is minor in comparison to the importance of having a comprehensive work, written in an accessible style, that pulls together previous resources and relates them to Ulmer’s personal life and business struggles. Ulmer was perhaps the ultimate iconoclast, but he also craved acceptance, and would like to have worked among the best in his field. “An inveterate dreamer,” Isenberg writes, “Ulmer never gave up on the idea of making movies in Southern California’s factories — he simply adjusted.” This fascinating biography gives us the chance to weigh the many frustrations in Ulmer’s career against the joy he found in the act of creation.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.