Short Fuse Interview: The Enigma of Vo Nguyen Giap — Military Mastermind, or “Marginalized Hero”?

If we lift the fog hovering over the War in Vietnam what we find a story nearly unknown in the West: far from devising and launching the Tet Offensive, Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap consistently and adamantly opposed it.

By Harvey Blume

So far as Vietnam goes, the fog of war — as Errol Morris called it, in his documentary about former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara — is particularly dense and durable. Far from dissipating over time, it continues to obscure our understanding of the war in Vietnam and of how, and by whom, the vastly outgunned Vietnamese were marshaled to defeat the United States in that terrible conflict.

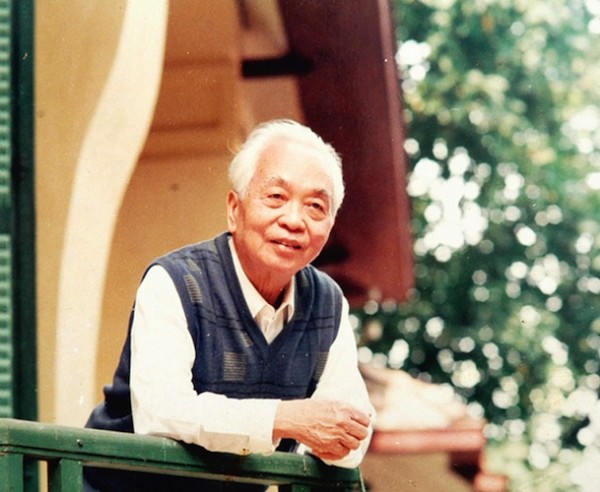

This enduring fogginess becomes apparent in obituaries for General Vo Nguyen Giap, who died in early October at age 102. The headline in the NY Times obit, for example, typical of most, read: “Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, Who Ousted U.S. From Vietnam, Is Dead”. In fact, Giap had little to do with ousting the U.S. from Vietnam. On the contrary, he himself had been ousted from leadership of the Vietnamese Communist Party by then, and along with his followers, faced imprisonment.

The Times goes on to credit Giap with launching the “Tet offensive of 1968, when North Vietnamese regulars and Viet Cong guerrillas attacked scores of military targets and provincial capitals throughout South Vietnam.” The obit recapitulates the prevailing view that the Tet Offensive was, in purely military terms, a disaster for the North Vietnamese but at the same time an incalculable political victory. Tet, as reported in the media and, especially, as seen on television, raised doubts about American involvement, fueled the anti-war movement, and among other things, prompted President Johnson not to seek a second term.

But if we lift the fog hovering over the War in Vietnam what we find is a story nearly unknown in the West: far from devising and launching the Tet Offensive, Vo Nguyen Giap so consistently and adamantly opposed it that he was purged.

Americans didn’t know much about Vietnam when we chose to take up where the French had left off. Do we wish to know more now? And what of other places in the world where we project military might while treating the target culture and history as terra incognita? There is, for example, in the Muslim world, a split between Sunni and Shiite Muslims, that we are only now, however reluctantly, learning about, years after exacerbating this schism with our invasion of Iraq.

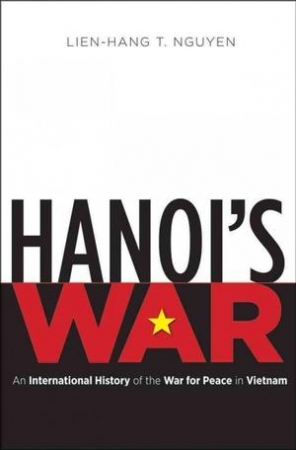

Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, a Vietnamese-American scholar, has written an eye-opening history of the war in Vietnam; it tells a story, from the Vietnamese side, drawing on previously unavailable sources, that lifts much of the fog that continues to obscure the War in Vietnam. I contacted Lien-Hang T. Nguyen to ask how she remembers Vo Nguyen Giap. This is her reply.

***

The death of General Vo Nguyen Giap closes a tragic chapter in the shared history of the United States and Vietnam. America’s Vietnam War and Vietnam’s Anti-American Struggle for Reunification and National Salvation is undeniably one of the most important episodes in both country’s modern history. But the man often found at the center of the twin narratives, General Giap, remains enigmatic. Despite outliving his adversaries and comrades alike, Giap did not have the final word. And now with his death, we may never get the full picture of that war or his role in it.

Growing up in the United States as a Vietnamese American after the war, General Giap was presented to me as a revered villain. The vanquished community of Vietnamese refugees who fled the country in 1975 and after pointed to Giap, and Ho Chi Minh, as the main architects of the communist war. Likewise, post-Vietnam War America identified Giap as the military tactician behind Hanoi’s victory. In both representations, he was the cunning general who outsmarted the French first, and then later Americans and their South Vietnamese allies.

His international reputation was equally impressive. Giap’s writings have been translated into dozens of other languages and studied by revolutionaries worldwide in the post-Vietnam War era. Alongside Mao Zedong and Che Guevara, Giap’s contribution to revolutionary guerrilla strategy inspired national liberation fighters throughout the developing world, including Palestine, Angola, and Nicaragua. His teachings revealed how guerillas could take on and defeat larger, and more powerful, enemies. U.S. style counterinsurgency held many weaknesses, and Giap could point them all out.

In country, though, the story was different. Despised and distrusted by those in power – Le Duan and Le Duc Tho – General Giap could only enjoy his international stature, and not his internal position. The “comrades Le” had identified Giap as a threat to their power during the anti-American struggle, but they had to wait until after the war to remove him from the political scene. In 1980, Giap was no longer minister of defense and in 1982, he lost his seat in the Politburo. By the early 1990s, Giap no longer held any political office. Stripped of key state and Party positions of leadership, Giap was relegated to ceremonial roles.

What most people don’t know is that this marginalization began much earlier than the post-Vietnam War era.

Beginning at the start of Hanoi’s war in 1959-1960, Giap had already begun his downward descent at the hands of Le Duan and Le Duc Tho, the men whose names should be synonymous with the Vietnam War. With the return of Duan to Hanoi, Giap lost control over the drafting of Hanoi’s war resolution to Duan. In 1963-1964 when Duan decided to “go-for-broke” and defeat the Saigon government before the Americans could intervene, Giap was powerless to prevent what he saw as a foolhardy strategy.

In 1967-1968, Giap’s objections to Duan’s risky General Offensive and General Uprising strategy, what would become known as the 1968 Tet Offensive, cost him dearly. Duan and Tho arrested his deputies for treason, in an effort to implicate the general as part of a revisionist plot to overthrow the government. During this period from 1963 to 1967, Giap too was under the scrutiny of Duan’s security forces and the famous hero of Dien Bien Phu even fled abroad to escape the political pressure in Hanoi.

In 1972, after regaining some of his military influence due to his success in Laos, Giap dared to speak out against Duan and Tho’s preferred full-frontal attack across the DMZ during the 1972 Easter Offensive. Once again, his objections fell on deaf ears as North Vietnamese troops on top of Soviet tanks crossed the Seventeenth Parallel. Had they been heeded, Giap’s words of caution throughout Hanoi’s war might have still resulted in Hanoi’s victory but without the staggering costs.

Carefully avoiding the period of the Vietnam War for fear of greater retribution by the acolytes of the “comrades Le,” Giap did not leave memoirs addressing this crucial period. Instead, he let others do the talking. What we know of Duan and Theo’s treatment of Giap is based on accounts by lower level Party officials, post-war interviews with dissidents, and more or less gossip permeating Hanoi that managed to trickle abroad. More recently, a publication by an insider journalist and blogger has revealed more of these state secrets and cast greater light on the internal power struggles taking place in Hanoi.

But nothing from Giap himself, despite living to 102. Now as a Vietnam War scholar who has written about internal Hanoi politics, I can only hope to find an unpublished manuscript by Giap, or at least one sanctioned by Giap, that will address these lacunae in our understanding Hanoi’s war and his role in it. Until then, Giap’s silence has rendered him not as a revered villain, but rather a marginalized hero.

— Lien-Hang T. Nguyen

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: General Vo Nguyen Giap, Hanoi's War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam, Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Short Fuse

I studied the Vietnam War and some of the literature that came out of the conflict (for a semester with H. Bruce Franklin. That course forever altered my understanding of the United States. This is not a period of history that should be buried — quite the opposite. A course such as Franklin’s should be mandatory for all American high school students, who need to understand how — and why — truth and the facts diverged from the cover stories spun by politicians and the media. This is a fascinating post, all the more since it spotlights a Vietnamese point of view. I am deeply gratified to see The Arts Fuse recognize that Vietnam far, far from old news.

Writers always are quick to comment on how General Giap was such a hero. But I think General Westmoreland said it best. General Giap had his troops slaughtered and their lives seemed to matter very little to him. Most writers will also never tell you America never lost a major battle in Vietnam. The final chapter in Vietnam – for those who want the facts — is that after we LEFT in 1973 the South Vietnamese Army held it on its own for almost two years until corruption and poor morale over took the south. The NVA and the Vietcong fought with honor and bravery and should be respected for that. And NO Vietnam Vet ever needs to feel ashamed for his service or duty which they gave for their country.