Theater Symposium: Who Wrote Shakespeare?

By Caldwell Titcomb

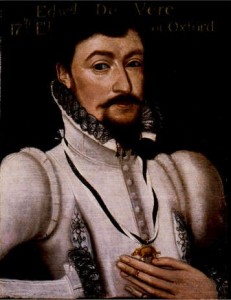

Starting in 1769 serious questions have been raised as to whether William Shakespeare (1564–1616) of Stratford-upon-Avon actually wrote the plays and poems attributed to him. For some years the true author was claimed to be Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626). So far, at least 60 persons have been put forward as the rightful writer. Notable among them are Christopher Marlowe (1564–93); Edward de Vere (1550-1604), 17th Earl of Oxford; William Stanley (1561–1642), 6th Earl of Derby; and Roger Manners (1576-1612), 5th Earl of Rutland. The roster has not been restricted to men: it includes Queen Elizabeth I herself (1533-1603), and—a recent addition—the Jewish poet Aemelia Bassano Lanier (1569-1645).

Edward de Vere—Did He Write Shakespeare's Plays?

The Marlovians must deal with their writer’s widely witnessed mortal brawl at 29; they have to posit a faked death. With many plays in the canon generally assigned to the 1605-1612 period, the Oxfordians have to confront de Vere’s death on June 24, 1604.

A local group, mostly Oxfordians, recently gathered for a two-day event in Watertown, MA (May 29-30). The first day saw a one-man show entitled “Shake-Speare’s Treason,” written and performed by actor-turned-writer Hank Whittemore in collaboration with director Ted Story. This 90-minute dramatized lecture—a work-in-progress given in several cities—is distilled from Whittemore’s huge, 918-page tome The Monument, devoted to the Bard’s 154 sonnets.

It is Whittemore’s theory that Her Majesty was not the “virgin queen” she claimed to be. He maintains that Elizabeth began an affair with Edward de Vere in the late 1560s and, after staying out of public view for six months, bore a son, Henry Wriothesley [pronounced Risly], 3rd Earl of Southampton (1573-1624). Henry would join Robert Devereux (1566-1601), 2nd Earl of Essex, in the so-called Essex Rebellion against the government in 1601. This failed, and Essex was beheaded as a traitor, while Henry was reprieved and imprisoned in the Tower until Elizabeth’s death (the “three winters cold” in Sonnet 104). Henry, as royal issue, could have claimed the throne as King Henry IX, last of the Tudors. The Sonnets are viewed as written by de Vere to his son, the dedication to “Mr. W. H.” reversing the initials to conceal the identity of the addressee.

The second day was devoted to a series of illustrated talks, kicking off with an engrossing consideration of the Stratfordian’s will by Bonner Miller Cutting, president of the Lone Star Shakespeare Roundtable in Houston, Texas. The will, which was discovered in 1747, is, Cutting claims, “not an enigma, but a disaster.” She has examined some 2,000 wills, and is amazed at what is not present in this one: nothing about books, manuscripts, musical instruments, maps, bequests to servants, or forgiveness of debts. She regards the celebrated bequest of “the second best bed and the furniture” to the testator’s wife (who is not named) as intentionally disparaging, whereas his sister Joan (named three times) is well provided for. The text is heavily revised, and two different inks were used, with the redrafted first page written later than pages two and three.

Journalist Mark Anderson addressed two topics in his remarks. He first spoke about the recent excitement in the media around the world concerning the Cobbe family’s portrait asserted by some, including well-known scholars, as a depiction of Shakespeare. Anderson mentioned a Times Literary Supplement article by Katherine Duncan-Jones, co-editor of the “Arden Shakespeare’s Poems” and author of a biography of the Bard. I tracked down the article (March 18 issue), and she persuasively proves that the Cobbe painting is one of several copies of a portrait (ca. 1610) known to be of Sir Thomas Overbury (1581-1613). Much ado about nothing.

Anderson then put on his other hat as the author of “Shakespeare” by Another Name, his 2005 biography of Edward de Vere as “the man who was Shakespeare.” He stated that the plays characterized people from de Vere’s life—which is plausible. Not so convincing was his statement that the author “stopped creating new work in 1604, stopped reading in 1604, stopped reporting in 1604.” He proposed that the standard chronology of the writings is “a polite fiction.”

We were then shown the beginning of Cheryl Eagan-Donovan’s film documentary about de Vere entitled Nothing is Truer Than Truth (an English translation of the de Vere family motto, “Vero Nihil Verius”). This film-in-progress, based on Anderson’s book, will eventually run 60 or 70 minutes and will emphasize de Vere’s visit to Venice in his mid-20s. From the opening 15 minutes, one recognized two interviewees familiar to Boston audiences: Diego Arciniegas, award-winning actor and artistic director of the Publick Theatre; and Robert J. Orchard, executive director of the American Repertory Theater.

After a half-hour Twenty Questions game about Shakespeare and de Vere, we got back to serious business with a presentation by poet Marie Merkel, author of a book on Titus Andronicus. She was struck by a statement in the influential critic Harold Bloom’s essay on The Tempest (“Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human,” p. 673), “Mysteriously, it seems an inaugural work, a different mode of comedy, one that Beckett attempted to rival in ‘Endgame.’” And she cited the 2002 edition of the play by David Lindley, who spoke of the work’s “uniquely experimental nature.”

So Merkel decided to explore fully the specialness of this play. Among the features she found were staccato cadences, heavy enjambment, rhetorical austerity, neoclassic structure, the classical unities, and strong echoes of the masque and commedia dell’arte. She also compiled several dozen words that occur in The Tempest and in Ben Jonson (1572-1637) but nowhere else in the Bard’s plays.

Ben Jonson, claims a critic, wrote The Tempest and kept it a secret.

Her conclusion is that The Tempest was written by Jonson, who, she says, was still obsessed by this play in 1631. She doesn’t explain how Jonson came to provide his lengthy prefatory encomium to “my beloved, The AUTHOR Mr. William Shakespeare” in the 1623 First Folio of the plays, in which The Tempest was printed first. She is preparing a book on Jonson and the play and will doubtless address this question.

The final symposium talk, “Shakespeare and the Succession Crisis of the 1590s,” was given by librarian and longtime Oxfordian Bill Boyle. His remarks were complex and resistant to easy summary. But he spoke of historian Sir John Hayward (ca. 1564-1627), who in 1599 wrote about the deposing of Richard II, the subject of the 1597 First Quarto of the Bard’s wonderful play. Boyle considers the play “a real legal treatise,” and it was by request performed on the eve of the Essex Rebellion. Boyle also talked about the long epic poem “Willobie his Avisa” (1594), which contains the first mention of Shakespeare and in which Avisa might have been a reference to Queen Elizabeth. And he spoke about Francis Meres’ “Palladis Tamia” (1598), which listed a lot of plays and poems and saluted the “mellifluous and hon[e]y-tongued Shakespeare.”

Members of the U.S. Supreme Court have occasionally been corralled to judge moot trials about the authorship controversy—one took place in 1987, with Justice John Paul Stevens participating. Jess Bravin in a recent issue of the Wall Street Journal (April 18) updated the subject in an article distributed to symposium attendees. Justice Stevens now says of the Stratford man, “I think the evidence that he was not the author is beyond a reasonable doubt,” and he sides with the Oxfordians, as does Justice Antonin Scalia. Justices Kennedy and Breyer stick with the Stratfordians. Justices Souter and Ginsburg are unsure, and Justices Roberts, Thomas, and Alito declined to comment.

Those who are new to the controversy or desire further argument should turn to the website DoubtAboutWill.org, which provides a Declaration of Reasonable Doubt and a debate by scholar Stanley Wells with Shakespearean actors Mark Rylance and Sir Derek Jacobi.

Full disclosure obliges me to state that in my youth I was an ardent Oxfordian. [The founder of the Oxford theory (1918) was the somewhat unfortunately surnamed J. Thomas Looney—pronounced, however, to rhyme with Tony.] In the last half century, however, I have—for better or worse—rejoined the orthodox Stratfordian mainstream. But there remain a host of questions that have not been satisfactorily answered by anyone. So the battle will certainly continue for a long time.

Tagged: Aemelia Bassano Lanier, Ben Jonson, Caldwell-Titcomb, Edward de Vere, Shakespeare, The Tempest. Hugh Whittemore

In the century or so it took to establish firmly the immortal reputation of Shakespeare’s poems and plays, all the documents that could conclusively resolve the Shakespeare Question vanished forever. The precious little that has survived about the Bard directly supports the Stratfordian side. All competing positions thus rely on various amounts of wild conspiracy theory, tortured chronology, wishful hunting, and outright fantasy. Hard evidence doesn’t enter into it.

Dear Caldwell Titcomb

Thank you for a comprehensive and balanced review of our symposium. I was surprised to realize we’d covered so much ground! Re: Jonson’s prefatory encomium: Oxfordians have given this poem, and Jonson’s role in the First Folio no small amount of scrutiny, so I will, indeed, be building on this body of research in my book. A brief synopsis of my case will appear in the Shakespeare Oxford Society Newsletter in Sept. ’09.

I look forward to seeing you at our next event.

M.M.

Bravo Dr. Titcomb! As always, you are perceptive, persuasive and enlightening. Your knowledge of the theater is second to none.

J.G.

I agree with Peter Walsh that the preponderance of the evidence, along with common sense and a stroke or two of Occam’s razor, substantiates the Stratfordian side.

The dogged phenomenon of the Stratford deniers is a much more interesting psycho-aesthetic question.

I must admit, as a long-time lover of the plays of Ben Jonson, that the notion that he, not Shakespeare, wrote “The Tempest” tickles me. But why wouldn’t Jonson admit to authorship? He was no shrinking violet when it came to taking credit. It makes no sense, outside of tangled paranoid delusions embracing blackmail, dank conspiracies, and secrets held to the grave.

Bill Marx

The absence of evidence does not logically constitute proof of conspiracy to hide it. But it is often taken that way.

No matter who wrote “Shakespeare”, the Jonsonian elements of The Tempest are hard-wired into the play. Conspiracy not required here: my theory is that Jonson wrote it as a deliberate forgery of his master, paying Shakespeare homage by revisiting his themes even as he slyly put them all through a “sea-change”. Why’d he do it? For the fun of it; because he could; because the audiences wanted “Sweet Shakespeare” instead of what he thought was good for them.

Think of it: if you had the skill to pass off a play as Shakespeare’s – or a painting as Rembrandt’s, an opera as Mozart’s – and you’d gotten away with it once, would you ever want the hoax to end? In 1623, he saw his handiwork pass the ultimate test: canonization. Wow. So when does he step forward and say, “gee, guess what, guys?”

On the other hand, if it had come down to us as “The Tempest, by Ben Jonson”, we’d all be judging the play as more of jealous Ben the Bricklayer, sweating under the anxiety of Shakespeare’s influence. Instead, he got the last laugh. As his host in Scotland, Sir William Drummond remarked, Jonson was “given rather to lose a friend than a jest.”

The problem(s) with Ms. Merkel’s assertion is that, of course, The Tempest is far superior to anything Jonson ever wrote in its plot and imaginative atmosphere, and its tone and poetry are utterly unlike Jonson’s own – plus the play is clearly not a parody but a distillation of the Bard’s own oeuvre. So we’re being asked to ponder a parody that also functions as a valedictory. And let’s be honest – could Jonson, known for his vengeful moral determinism, ever pull off an ode to forgiveness so persuasively? Of course if you willfully ignore all that – or cannot perceive all that yourself yourself – then yeah, sure, maybe The Tempest was written by Ben Jonson.

There’s no general agreement among scholars that Jonsonian elements are “hard-wired” into “The Tempest.” That is your claim. And I don’t see any historical evidence that Jonson accepted Shakespeare as his master – Jonson had a very, very healthy respect for his own and the Bard’s genius.

But even if I accept “The Tempest” as Jonson’s, your theory explaining why he didn’t take credit for a masterpiece makes scant psychological sense.

If, as you suggest, Jonson wrote the script just for “fun” what is the point of the joke? What’s funny about a jape if no one but the jokester knows the punch line? Your Jonson is content to chuckle quietly in his room, chortling that he had penned a play the world accepted as written by Shakespeare. (Why the Bard didn’t point out the deception is puzzling. Was he in on the joke? Were they at least dividing the box office take?)

Your Jonson, in paranoid fashion, prefers to keep the secret of his authorship to his death. In his final years Jonson was physically ill, out of theatrical fashion, and badly in need of cash. Surely proving his authorship of “The Tempest” would have brought in some money, welcome fame, and free meals. But your Jonson is having too much “fun” lying in pain, ignored, congratulating himself that he has fooled the world.

Think of the much more plausible dramatic possibilities: the 1623 texts are published, “The Tempest” canonized. Jonson reveals, with suitable flourish, that he wrote the play to a stunned theater community, a flabbergasted London society. What dramatist could resist proving to doubters and scoffers that he is as brilliant as Shakespeare?

Or how about one of the many boisterous nights of drinking in the pub with the worshipful “Sons of Ben?” A well-lubricated Jonson picks up the 1623 text and, with a roar of triumphant laughter, lets out his secret to cries of incredulity followed by yelps of admiration. Your Jonson, impervious to drink (!), the temptations of his huge ego, and human nature would say and do nothing to spill the beans.

Of course, maybe Jonson did tell others (who, of course, would tell others) or write something down: it would only be natural. That would be big news, which is why your theory depends on his complete silence. Complicated conspiracy theories, beloved of non-Stratfordians but unconvincing to others, would come in. Jonson is ordered to keep mum about “The Tempest” or die. Mysterious hooded figures hand out bribes (alas, none to Jonson) to those in the know, destroy documents, buy off the traitorous Sons of Ben …

Bill Marx

Alas, unless you demand solid documentation, you can “prove” just about anything from context, coincidence, and some creative speculation.

Using the Oxfordian line of reasoning, for example, you can expose William Randolf Hearst as the true author of “Citizen Kane.” After all, whoever put together that screenplay sure knew a whole lot about what it was like to be a rich, egotistic newspaper magnate living in an enormous neo-baroque castle with a wannabe opera star.

And didn’t Hearst hang out with all those Hollywood types, providing plenty of opportunity to cook up a movieland scam? Hearst’s lawsuit against his old drinking buddy, Orson Welles, was just for laughs and publicity, cooked up by his very talented press agents. And “Rosebud” was actually the nickname of an assistant gardener at San Simeon. Could anyone outside the Hearst circle have known that special detail?

Case proved.

The Citizen Kane analogy is doubly appropriate in that the film is rather a more accurate psychological biography of Orson Welles than it is of William Randolph Hearst. Thus even if Edward da Vere served as a model for key Shakespearean characters, he may nevertheless have been merely a device for revealing Shakespeare himself.

Actually, having looked into the matter, I think you can make a much stronger case that William Randolf Hearst wrote “Citizen Kane” for Edward de Vere as author of anything attributed to Shakespeare. Here are a few highly suggestive factoids:

1. The authorship of the “Kane” screenplay has always been disputed. Although veteran writer Herman J. Mankiewicz and the much less experienced Orson Welles shared official credit, and an Oscar, for the script, a furious Mankiewicz later claimed he wrote every line well before filming began. Critics and film historians have debated the question of authorship ever since. The truth remains, though, that no one knows for sure who the true author or authors were. Therefore, can Hearst’s role as author or co-author of the script be positively excluded?

2. Mankiewicz was part of the Hearst circle and a regular visitor to San Simeon. This gave him ample opportunity to work with Hearst, who was obsessed with and deeply involved movie-making and his own fame, in developing the idea of the movie and producing the script. At the time, both Mankiewicz and Hearst had far more experience with movies and screenwriting than did Orson Welles, who was still in his mid-20s. There is ample evidence that the idea for the movie originated at San Simeon, not with Welles. Can there be any doubt that Hearst and Mankiewicz were the true creative forces behind “Citizen Kane?” Isn’t it also highly suspicious that Welles never again reached the standard of “Citizen Kane” during the rest of his long career?

3. Although Hearst at least went through the motions of trying to destroy “Citizen Kane” before it was released, there is no evidence that he ever had a falling out with Mankiewicz over his role in creating the script, despite the fact that Mankiewicz’ role was, in reality, a far greater breach of their friendship than anything Welles did. Doesn’t this indicate that Hearst was, in fact, colluding with Mankiewicz?

3. Hearst’s attempts to “destroy” the movie before it was released seem half-hearted at best. Does anyone really dispute the fact that Hearst, with his enormous power and connections in the national press and in Hollywood, could have prevented the release, if not the original production, if he had truly wanted to? Hearst seems to have been only going through the motions to cover up his own involvement in the film.

4. Heart’s motive in preventing the release of the film was how it portrayed his long-time mistress and companion, the Hollywood star Marion Davies. Yet Hearst had many reasons to be upset with Davies. She is widely believed to have had an affair in the 1920s with Charlie Chaplin, while she was simultaneously living at San Simeon and involved with Hearst. In 1924, it is alleged, Hearst, in a jealous rage tried to shoot someone he thought was Chaplin during a party on Hearst’s yacht. In fact, he shot and killed the film producer Thomas Harper Ince. According to the story, Hearst not only had to go to great lengths and bribery to cover up the murder, he later is said to have learned that the Davies-Chaplin affair continued into the 1930s. Could “Citizen Kane” have been Hearst’s means for getting revenge on Davies without revealing his role in the Ince murder?

5. Mankiewicz was a close friend of child prodigy and screenwriter Charles Davies Lederer, Marion Davies’ favorite nephew, who essentially grew up at San Simeon under Davies and Hearst’s care. Lederer undoubtedly knew all the scandals and gossip surrounding the Hearst Circle. Lederer married Welles’ ex-wife, Virginia Welles, giving him access to all the scandals and gossip about Welles. Yet Welles and Lederer also became close friends. Doesn’t all this suggest a coziness, bordering on conspiracy, between Hearst, Lederer, Mankiewicz, and Welles? Can anyone doubt that Hearst was far too close to the others not to know about the “Citizen Kane” project— or was he, in fact, involved in creating it?

Can anyone doubt, after reading all this evidence, that Hearst wrote “Citizen Kane,” perhaps in collaboration with Mankiewicz and Lederer? Or perhaps coincidences like these are just too tempting to those who want to spin new theories of authorship.

I’m delighted that Caldwell has returned to the Stratfordian fold. For a concise and graceful history of the anti-Stratfordians, see “The Poacher from Stratford” by Frank W. Wadsworth. Even more concisely, Alfred Harbage, in an essay entitled “Shakespeare as Culture Hero” (in Harbage’s book “Conceptions of Shakespeare”) suggests that the real question is the question “not of whether [Shakespeare] wrote his plays, but of why there have been persistent claims that he did not.” Harbage concludes that “The attacks upon Shakespeare’s authorship . . . must be referred, not to the realm of biographical and literary evidence, but to the realm of mythmaking. . . . The impulse accounting for these attacks is the same basic impulse which accounts for the creation of our Siegfrieds and our King Arthurs.”

Robert Benchley answered the “Who wrote Shakespeare’s plays” question with this off hand remark:

Shakespeares plays were written by another man with the same name.

It’s simply not true that questions about the authorship of the plays go as far back as stated here. The anti-Stratford theories started bubbling up in the 1850s, 200 years after Shakespeare was dead. Contested Will by James Shapiro is an excellent and entertaining account of the history of this strange, anti-intellectual, paranoid conspiracy mindset.