Fuse Commentary: Papercut and the Past and Future of the Zine

Papercut’s mission is to collect, catalog, and make available to the public the widest possible collection of contemporary ‘zines.

At Papercut -- A Zine on Glass

By Dylan Rose

I’m new at this reporting bit and, in an early conversation with my editor about the particular goals and restrictions of the genre, I blundered: I happened to refer to Arts Fuse as a “ zine.” I was at this time made to understand that the term “zine”—a small, self-published magazine about a particular subject—is now somewhat passe. “A zine,?” he asked, “Who’s making zines anymore?”

Ordinarily I would have simply apologized for the blunder—to peeve an editor is, as I understand it, a journalistic high crime—but I could not in this case have made the apology sincerely. Although I believe his question was intended to be rhetorical and instructional, it does have a definite answer. The answer is that the zine is in fact still a vital form and, as I have been recently made to understand, it shares a great deal in common with projects like The Arts Fuse.

The Zine

Self-publishing is a practice that extends as far back as the original printing press, but true modern zines are generally held to have first emerged in the middle of the last century, when the increasing success of magazines like Popular Mechanics created a demand for DIY and kit-based home-improvement projects for interested amateurs. The development of the zine as a distinct publishing form quickly accelerated, growing to encompass a wider range of artistic, religious, and technical topics.

Adopted first by the hippies of the middle ‘60s and later by the punk and grunge music cultures of the 70s, 80s and early 90s, the zines’ comparatively low publishing cost and relative ease of distribution supported the counter-cultural and frequently anti-consumerist creeds of these groups. DIY instructions for sewing one’s own clothing, tips and techniques for recording and marketing one’s music, and spiritual advice for interested seekers could in this form be quickly and easily distributed without recourse to commercial publishing houses. Zines also became a tool for exposing interested communities to one’s creative work: many modern, privately printed literary magazines still operate on the production and distribution template set down by earlier literary zines.

Although many individuals continue to edit and publish zines, like television and the podcast quickly eclipsed radio, so too has the internet and the blog brought the axe to many zine enterprises. The simple fact of the matter is that a zine, no matter how cheap, does cost some money to produce.

Even if one hires professionals to design and maintain a personal blog, this expense—even over time—in no way compares with that of the necessary costs for sending out requests for content, paying for editing or layout software, and printing and binding one’s zine. Many zine creators see the expense of their production as a sign of their love and dedication to their fields or as a form of opposition to oppressive consumer economics, but the intersection of the large required time-commitment and their low (read: zero) rate of return means that only the most popular zines could hope to break even.

Papercut

That said, the Papercut Zine Library (once a Harvard institution, now relocated to Somerville, MA) is proof that zine creators will find a way to keep their tradition alive. Occupying a single crowded room on the third floor of an renovated art-space (no elevator, either), Papercut’s mission is to collect, catalog, and make available to the public the widest possible collection of contemporary zines.

Operating largely through donations of both cash and material, Papercut is still a lively enterprise. New material is brought in regularly enough that the old and decaying is soon relegated to the library’s archives. In spite of the occasional purges, the library’s shelves are nearly always stuffed to capacity; zines spill out of their place and are reshelved crazily, quickly lost or forgotten. This gives the place the same kind of home-built, quirky character that the zines themselves possess.

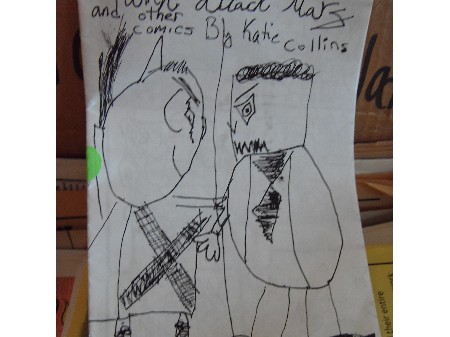

Zines for all ages

Although this vibe is mostly charming, it can’t be denied that some of the zines that end up here embody this aesthetic a little too thoroughly. After grabbing a random handful from the shelves, I soon discover the great flaw and weakness of the zine “production by photocopy” method: a print item, too often reproduced, soon becomes illegible. The images on the covers of these misfires are muddles of black ink; whatever their titles were once intended to convey has been lost to history.

Often enough these works become the victims of other distortions: poor grammar and spelling, editorial laxity, or an apparent taste for Dada renders others frankly unintelligible. In pulling one from the shelves, I discover that cost-saving measures in binding and paper selection remain, at the last, only corners cut: poorly inserted staples come loose, pages flutter, and I am left holding the emptied and not fixable shell of someone’s creative labors.

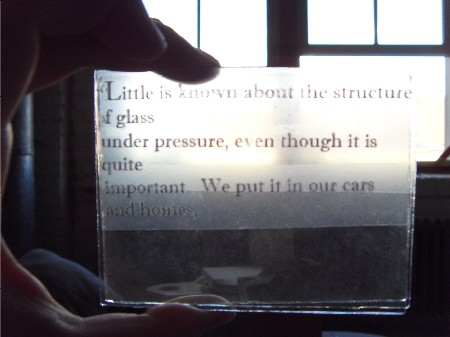

This was certainly not the case for most of what I saw at Papercut, however. Some of the zines I found there were crafted lovingly, even beautifully. One zine I was directed to had been printed directly onto glass by some obscure photographic technique. Another came in a small, intricate, origami-like package with a mini-cd of music and a folio of photographic prints. Others were bound with ribbon or lace on paper that was smooth and cool and shone in your hand like gold-leaf.

Most marvelous of all was the tiny, aluminum pill tin I discovered on one of the shelves, which contained a tiny scroll of paper on which a list of 30 or 40 items that “could fit into this tin.” The zine here also lived up to its reputation as catering to the tiniest of niche interests: pamphlets on cybernetic theory jockeyed for space on the shelves next to raw-food, diet instruction manuals and tracts on magical theory and practice. I laughed aloud at the small, absurdist comic strips and one-liners, which were crammed into the margins of others.

Binding it Together

Reeling from the shock of discovering so many artful and interesting publications stuffed into so little space, I turned to face a newly chimeric assignment: by what conceivable standard could all of the paper and glass and lace and tin in this room be bound together by a single name? Certainly it was not a single theme or subject of content. And it is true that not just anything qualifies as a zine: a small percentage of the total material that ends up at Papercut every month is turned away or filed as “miscellaneous.” So where is the line? What separates the zine from the non-zine, the zine from (drum-roll please) a blog like The Arts-Fuse? Is there something that these publishing forms share, and can they be placed in fruitful dialogue?

I thought I might get a toe-hold on these problems by talking with a friend of mine, Ms. Mary Lechner of Olympia, Washington, whose own zine,This is Madness, This is Sense, has just released its second issue. She suggested that the appeal of both blogs and zines is that they “both give people the freedom to create and express, without the limitations of more formal publishing frameworks.” This was a pretty common thread in most of what I read and talked about with people at Papercut: self-publishing is basically hassle-free. Where the two publishing forms divide, ultimately, is in the choice of medium.

Zine as a small, intricate, origami-like package with a mini-cd of music and a folio of photographic prints.

Ms. Lechner expressed a preference for the zine over the blog “because I really believe there’s something powerful about holding the work in your own hands—it creates a more visceral, holistic experience.” There really is something special to be said for the experience of holding these works in your hands. Reaching into a random stack of zines feels a little bit like putting one’s hand into a candy jar: the sight, the feel, and anticipated taste of what is therein contained produces a sensually rich experience.

That said, the blog is often more cost effective and has a broader potential range and depth of coverage. Blog creators also have a much more powerful set of tools at their disposal for dispersing their work: social-networking has enabled instant cross-referencing of information with a nearly limitless “blogosphere.” While Papercut relies on heavily on word-of-mouth and an active arts presence within the community—they host regular acoustic shows and art-openings—it seems hard to argue with the fact that content that is posted directly to a person’s blog can be shared in similar communities around the globe. If I wish to browse Papercut’s library, I have to trek out to Somerville; one need travel only as far as one’s laptop to see what has been posted to The Arts Fuse today.

It would be cheesy to conclude by suggesting that these differences are ultimately superficial, and that both forms of publishing are “special and unique in their own way.” I’ll therefore side-step the cliche and say only that differences between what a blog like The Arts Fuse does and what the creators of zines do really are two entirely separate things. The one raises a standard in favor of ease of distribution and technological relevance; the other a battle-cry for “process over results!” What these two enterprises do share, something which delights me in both cases, is that they both play marvelously with the scale of our attention.

To spend an afternoon at Papercut is to stumble upon endless, miniature marvels of art; it is a feast for the senses that, unlike many other such feasts, requires our careful and minute attention. The same could be said of what The Arts Fuse does. “Support local authors!”, it exclaims, “Put down your remote-control and spend an evening at a local theater!” These are the facets of modern, urban life, which, if we are not carefully and minutely attentive of them, are easily lost to louder and flashier diversions.

Tagged: Dylan Rose, Paper-Cut, Somerville, magazines, online publications

I’m sure those dedicated to traditional zines will resist this, but in the future I see a large market and appetite for magazines, whether backed by a reputable publisher or not. One need only to look at something like the iPad or other tablet PCs to see that the devices of tomorrow will be perfect for full-color and well-designed editorial content. As a magazine journalism major I may be biased, but I hope that zines will be for the iPads what podcasts were for iPods – an unexpected use of technology that leads to a reinvention of a dying field (as podcasts were for radio, digital zines would be for magazines).