Commentary: “Deluge” — How Vermont Survived Tropical Storm Irene

I fully support the themes that Peggy Shinn explores, articulated in Deluge’s subtitle: this one small state did save itself.

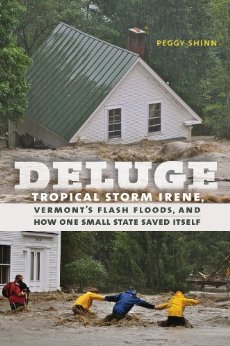

Deluge: Tropical Storm Irene, Vermont’s Flash Floods, and How One Small State Saved Itself by Peggy Shinn. University Press of New England, 232 pp., $27.95, $22.99 ebook.

By Jennie Marx

As a resident of Bethel, one of the Vermont towns hard-hit by tropical storm Irene, there were some things I knew before reading this book. I knew that five neighbors working as a bucket brigade could empty a basement with a foot of standing water in about eight hours (about 5,000 bucketfuls) to the point that the remaining puddles, greasy and rank, could be mopped up. I knew that, in other basements, the White River’s displaced silt created mud so tenacious it would immediately coat whatever implements were used to remove it. Once in pails and ferried outside, the mud, an impossibly thick and foul-smelling dough, had to be cupped out by hand. I knew that a mailbox sitting on its upright post, hovering over the 12-foot chasm that used to be a driveway, is a sight not easily forgotten, even after the ground has been returned to normal.

What I appreciated most about Peggy Shinn’s book was what I learned from its multi-faceted perspective on the event. In the aftermath of Irene, which hit Vermont on August 28, 2011, and in the recovery that is still taking place, I have pretty much concentrated on my own region. A Vermonter living in a flood-ravaged area herself, Shinn has used the intervening years to research and craft the backstory of Irene as a storm, examining its meteorological background and surveying its sociological effects on the entire state and beyond. Shinn provides well-researched detail about the concrete (and asphalt) damages to the state’s infrastructure, particularly the roads, bridges, and historic covered bridges. She delves into the history of floods in Vermont, including the devastating 1927 deluge. She also explores the municipal and federal response to disasters in general and goes into how these efforts affected specific towns, businesses, and individuals.

Shinn has built the book around several compelling stories. A father and son in Rutland, municipal workers, lost their lives attempting to save the city’s water supply. A farmer in Royalton, who suffered severe damage to his property and crops, finds the energy to organize volunteers to gut local, flooded homes before mold takes hold. Competing contractors work together to rebuild a vital road at a breakneck pace, allowing access to towns that had been completely isolated. Thirteen Vermont towns were cut off from outside help for days and had to survive and repair themselves with what they had. (The do-it-yourself, apologize later mentality is a theme throughout the book). She uses mostly first-person interviews and news reports to give voice to the events, and they are harrowing evidence. The book is arranged so that specific accounts are presented in short episodes, interspersed with background and hard data.

As interested as I was in the analytical data, I found myself skipping around to read some of the first-person accounts. This was especially true during Shinn’s discussions of FEMA regulations, which I am well-acquainted with from my work taking minutes at Bethel’s selectboard meetings. FEMA projects are always on the agenda, even now. (Thankfully, the last few bridges are set to be completed by this fall.)

The considerable power of the personal stories made me aware of what a difficult balance Shinn had to maintain in this book. In the two years since Irene, many communities have published or distributed their own books about the event. In my own region, these include the Herald of Randolph’s The Wrath of Irene, which contains the collected newspaper articles about the event. The local school put out a booklet made up of the seventh graders’ recollections of the night of the storm, many of whom had to leave home quickly to avoid the rising waters. It’s called Grab Your Toothbrush and Flashlight! We’re Headed to the Neighbors. Almost everyone you meet around my region in Vermont has a story about Irene, and their recollections make for compelling reading. In taking Deluge to the next level, in crafting a book that could work as a solid introduction to the facts of this event for readers who might not have experienced it, there is the danger that the stories included in Deluge will be treated as objective truth, equal to the scientific and other data that surround them.

Because I have been involved with the ongoing talk of recovery and have seen the shifting of perspectives over time, this is my reservation. There are complex shades within Vermonters’s stories, flickers of dark as well as light. Deluge tends to overlook the variety of responses in an effort to inspire.

I fully support the themes that Shinn explores, articulated in the subtitle of the book: this one small state did save itself. Vermont’s long tradition of community support, hard work, and ingenuity was an immeasurable asset during Irene. I’m glad this story is being told because it is one that I saw with my own eyes. But, in the book’s effort to reach a wider audience, the subtleties of the individual experiences are diminished. When reading accounts of people you are acquainted with personally, you can easily compare what they say with what you know about them outside of the nightmarish event. Other readers don’t have this perspective. I didn’t know these complexities when I was reading people recounting the happenings in other parts of the state. But, when I got to descriptions of my own little town, I saw how much was left out or was overlooked. A Publisher’s Note in Deluge acknowledges that the stories included in the book represent only a small sampling of a mass of individual experiences and directs the reader to a website where they can share their own stories or read others.

As in any catastrophe, Vermonters’ responses were complicated because they were made under extreme duress; what one person would view as a prudent response another might interpret as indifference or worse. Under such pressure, people showed cooperation, selflessness, profound creativity, and sacrifice. But this event also offered revelations of raw, wounded emotions: anger, betrayal, loss, shame. Disaster is a catalyst for change, both good and bad.

By reading this book, I learned some things about the genesis of Irene, what gave her so much power. I count myself very lucky that my family and home were safe and that I had lived my entire life to that point never having seen such destruction. In Deluge I learned about the challenges faced by Vermonters across the state. I learned about what needed to be done to resurrect Vermont’s decimated infrastructure. I felt the deep grief as people described losing their homes and businesses, and my heart soared with pride when reading about what ordinary people did to save others and themselves. I want others to know what happened, but I recognize that doing so means unearthing difficult days for the world to see. I applaud all those who were interviewed for their courage and vulnerability and Shinn for telling the tale. But, more than anything, I look forward to a time when this is history.

Jennie Marx is a freelance writer, editor, and newspaper correspondent living in central Vermont. She has edited books for Inner Traditions International/Bear and Company in Rochester, Vt., and regularly contributes to The Herald of Randolph. She is the niece of Arts Fuse Editor-in-chief Bill Marx.

Tagged: Deluge: Tropical Storm Irene, Jennie Marx, Peggy Shinn, University Press of New England