Book Review: Israeli Novelist A.B. Yehoshua’s Fascinating “Retrospective”

This fascinating book ends, leaving the reader with all sorts of questions — but that is exactly what really good fiction always does. Opening our minds, etching characters in our imaginations, and generating all sorts of possibilities.

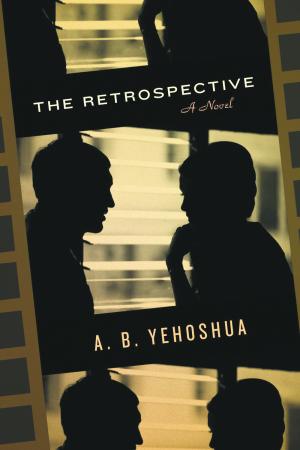

The Retrospective by A. B. Yehoshua. Translated by Stuart Schoffman. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 336 pages, $26.

By Roberta Silman

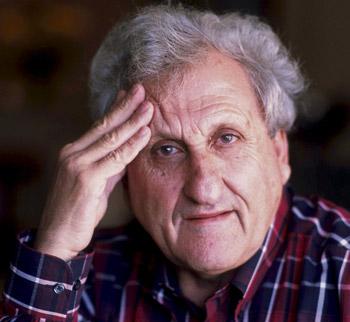

An Israeli, now in his late 70s, and from a Sephardic Jewish family, A. B. Yehoshua is one of the greatest fiction writers in the world today, and his newest book is one of his best. Some of my favorites among his writings are The Late Divorce, Mr. Mani, The Liberated Bride, and Five Seasons. What Yehoshua does magnificently is to fix his uncannily observant eye on a small situation and explore it thoroughly, thus giving it universal value. It is also why he is sometimes dismissed as a writer of “domestic” novels, which could be another way of saying he understands families and relationships all too well and is not afraid to write about them.

In this he resembles his compatriot, the great poet Yehuda Amichai who died several years ago. Another similarity between these two is their ability to write exquisite Hebrew. Because they are so gifted, and because they have both been lucky in their translators, their books in English have a surprising, almost miraculous, tenderness.

The Retrospective, whose Hebrew title Hesed Sefaradi means Sephardic or Spanish Compassion, begins with Yair Moses, whom everyone calls Moses, arriving with his muse, sometime lover, and dear friend, Ruth, at Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain for a retrospective of the films he has directed and in which Ruth has starred. Moses is divorced and although he and Ruth have never married, they are very close, and Moses is convinced that she is sick. His concern for her is one of the things that propels the narrative, finally pushing it into an unlikely place towards the end.

Two surprises await them in Santiago: 1) that the retrospective has been organized by a priest who is also host of the film archive, thus bringing in questions of religion and history, which of course involve the long and painful struggle of the Jews in Spain and 2) that over the large, but only, bed in their room is a painting called Caritas Romana, which depicts a young woman nursing a shackled, old man who may be a beggar, a prisoner, her father — no one is quite sure — or all three.

The painting triggers memories of Moses’s former screenwriter, Trigano, who was Ruth’s lover and his best friend until he and Moses parted angrily over the scene in an early movie that owed its conception to this very painting. If this sounds complicated, it is, and you have to pay close attention while reading this novel because although it takes place mostly in Moses’s head, everything has a purpose. The more you read, the more you realize that there are a lot more things on Yehoshua’s mind than an old man reviewing his early, and, some think, best work. You get a hint of what’s to come when he and his host, de Viola, have a conversation about the priest’s mother:

“And your mother,” says the director . . . “your mother also lives here in Santiago?”

No, his mother lives in Madrid, She is ninety-four, sharp of mind, though her body is infirm. She knows about the Moses retrospective and is one of its financial backers, and if she feels up to it, she will attend the prize ceremony on the third day. She is even familiar with a few of Moses’ films and believes in his future.

“My future?” Moses blushes. “At my age?”

“When the future is short,” the son quotes his mother, “it becomes more concentrated and interesting.”

The first half of the book goes into a lot of detail, some of it admittedly tedious, about the films being shown and both Moses’s and Ruth’s reactions. (For film buffs here’s a warning: all these movies exist only in Yehoshua’s head and in this book.) With mounting excitement, they watch the old films they made with the screenwriter Trigano, who grew up with Ruth, and the cameraman, Toledano, who died a gruesome death because of his love for Ruth. They hear questions, conversations, judgments; seeing the films leads to more memories and more questions, which they attempt to resolve as they make their way through an exhausting couple of days during which we become saturated with the smells and sounds in the heady atmosphere that is northern Spain.

As Moses works through the past, usually late at night — he has chronic insomnia — we learn his back story, not only professionally, but personally. Questions about his behavior, his need for control, his detachment crop up; there are also interesting ruminations and discussions about the creative process. And as Moses becomes aware that this retrospective is really the brain-child of his enemy, Trigano, who was here a year ago, he and Ruth become more honest, even ruthless, in their conversations. When Ruth, who now teaches young children in acting workshops, mentions a teenager hired to play her as a child, things begin to spiral out of control:

“ . . Because in those days I thought . . . and now too, really . . . I know that we—Trigano, Toledano, the lot of us — would always somehow stay a bit in the margins, so I was happy you gave me a little sister, so to speak, a twin who could strengthen me.” [Ruth says.]

“Again you?” [Moses says.]

“Me in the film.”

“What is this, the movie gets mixed up with reality for you?”

“Sometimes. And not for you?”

“Never. The boundary between reality and imagination is always there for me.”

“Because you never dare to stand in front of a camera, only behind it, because only from there can you be the one giving the orders.”

All celebrations, even small ones, come to an end, and the second half of this novel begins back in Tel Aviv and is more plot driven. The stakes seem to rise as Moses confronts his ex-wife, his daughter, Ruth, Toledano’s son, and his erstwhile friend, Shaul Trigano, all against the political uneasiness that is endemic to his homeland. In this section, the writing becomes increasingly urgent because we see so many of the themes of the book coalesce and we realize that Moses has other things to settle with himself. As we see different sides of him, he becomes emotionally richer, and we become more invested in him. While he and Ruth are traveling to the place where they once made a film, their conversation turns to the future hinted at in the beginning. But the way forward is not clear:

He gently touches her hair. Since Santiago she is linked in his soul not only with the characters she acted in his early films but also with the bare-breasted young woman nursing her own father. And though he still believes that all shades of her character have been exhausted and that even her remaining fans and followers would be wary of his giving her a new part, he fears that if he doesn’t, he will lose her forever.

And after he and Trigano finally meet — this section is written as if Moses were filming himself and is very powerful in its exploration of how tenuous a friendship can be — Moses knows he must return to Spain, to de Viola and his aged mother in Madrid. Accompanied by Toledano’s son, who is also a cameraman, he participates in a scene of Roman kindness that he once cut from one of his films. Infused with visions of Don Quixote, this fascinating book ends, leaving the reader with all sorts of questions — but that is exactly what really good fiction always does. Opening our minds, etching characters in our imaginations, and generating all sorts of possibilities. In short, The Retrospective, although wonderfully satisfying in many ways, leaves us wondering, and wishing for more.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. Her newest short story “The Sugar Road” can be found in the Digital Edition of The American Scholar. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.