Book Review: Denise Levertov — More Than a Famous Antiwar Poet

This meticulous biography of Anglo-American poet Denise Levertov is the labor of many years and of deep reflection and care.

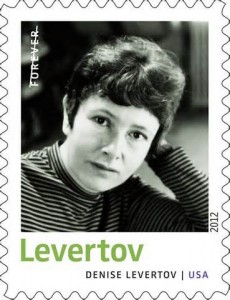

A Poet’s Revolution: The Life of Denise Levertov by Donna Krolik Hollenberg. University of California Press, 515 pp., Illustrated, $44.95.

By David Mehegan

It is a fit subject for a biography, the life of this extraordinarily prolific, Anglo-American poet. Born in England to a Welsh mother and a Russian-born Hasidic Jew who converted to Christianity and became a scholarly minister of the Church of England, this exotic bird ended her formal schooling at age 12, resolved early to be a poet, at age 24 married an American, and spent most of her life in this country. She was encouraged by T. S. Eliot, H. D., and Kenneth Rexroth, became a follower and friend of William Carlos Williams, and seemed to connect with every great and small poet of the post-World War II era, including the beats, Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, Adrienne Rich, W. S. Merwin, Louis Simpson, Muriel Rukeyser, Robert Bly, Galway Kinnell, Marge Piercy, Robert Creeley, LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), and many others.

Her style—lines of variable length with surprising stairstep enjambments, unadorned diction, intense feeling—strongly resembles that of William Carlos Williams, to whom she was devoted. Rilke was one of her aesthetic gods, both in his verse and in his philosophy about the work and high calling of the poet. Not many of her poems lack passion, though many are more rueful than despairing. There was never a hint of the vulgar in subject or sentiment, rather a certain fineness and elevation:

WEDDING-RING

My wedding-ring lies in a basket

as if at the bottom of a well.

Nothing will come to fish it back up

and onto my finger again.

It lies

among keys to abandoned houses,

nails waiting to be needed and hammered

into some wall,

telephone numbers with no names attached,

idle paperclips.

It can’t be given away

for fear of bringing ill-luck.

It can’t be sold

for the marriage was good in its own

time, though that time is gone.

Could some artificer

beat it into bright stones, transform it

into a dazzling circlet no one could take

for solemn betrothal or to make promises

living will not let them keep? Change it

into a simple gift I could give in friendship?

—Life in the Forest (New York: New Directions, 1978), 99.

She had one son and in 1974 was divorced from Mitch Goodman after 27 years, after which she lived a life that was both lonely and dense with activity, friends, and lovers. Though it ran aground, the marriage had given her access to the literary world and language of America, where she became more famous and successful than she might have been had she stayed in England. Most of her American life (she became a citizen in 1956) was spent in New York, Maine, Somerville, Mass., and Seattle, but she was peripatetic—traveling back and forth across the Atlantic to various European settings and all around North America, teaching at Tufts, Brandeis, Stanford, and seemingly dozens of other colleges and literary colonies and festivals. Though she never learned to drive, she seems to have been almost constantly on airplanes to somewhere, giving readings and appearing on panels.

In the 1960s and ’70s, she became active in the anti-Vietnam War movement, appearing at demonstrations and teach-ins. In 1972, she went to Hanoi with Muriel Rukeyser in solidarity, as she saw it, with the Vietnamese people. When her friends discovered that she had brought back to Boston some kind of small bomb (as a souvenir!) in her baggage, one of them persuaded her to let him pitch it off the B.U. Bridge. Presumably it is still in the river. Her political activism found its way into her poetry, and she is perhaps remembered disproportionately as a famous antiwar poet. But that, if true, is unfortunate, since this is a person for whom virtually every sort of intense moment, experience, or relationship might become a poem. In 1990, she was received into the Roman Catholic Church, and while that relationship, like all others, did not prove to be without doubt or difficulty, she never recanted. She died of lymphoma in 1997, age 74.

Donna Krolik Hollenberg, professor of English at the University of Connecticut, studied with Levertov and served as her teaching assistant at Tufts in the 1970s. She quotes extensively from her subject’s 1992 lecture, “Biography and the Poet,” at Ohio University: “The relationship between biographer and subject should be guided by the exercise of courtesy and consideration, she thought. There should be ‘frankness’ but not ‘public gluttony.’ Although she had sent her personal papers to Stanford with a future biography of herself in mind, Levertov feared one that might focus on the most scandalous of her personal peculiarities instead of making her work central. . . . Quoting Origo, Levertov commented on the good biographer’s ‘enthusiasm and veracity’ and warned against his or her ‘insidious temptations . . . to suppress, to invent, or to sit in judgment.’”

It is clear that Hollenberg tried carefully to follow these strictures. She does not invent or speculate. She does not directly criticize, does not judge, and does not, so far as we know, leave out any “scandalous peculiarities” (I noticed none that fit that adjective). Her admiring and affectionate view toward Levertov is clear; she almost always calls her Denise. She has read the poems and nonfiction lectures and essays closely. As the poet would have wished, she provides fairly close readings of many poems, relating them to their occasions and provocations in Levertov’s life. The poet kept extensive diaries, and they, along with letters and the testimonies of others, allow Hollenberg to track and report almost every place her subject went and with whom, what she saw and did, and most of all, how she felt about her life and experiences. It’s almost a month-by-month biography. Little escapes the biographer’s attention, or ours.

It was therefore a nagging fact to this reviewer that notwithstanding all the detail of life and textual analysis, Denise Levertov remains for much of the book an elusive figure, as a character if not as a poet. Partly this is because Hollenberg reveals her subject by unpacking the knowable facts,but also because she holds back, until quite late, from venturing into deeply examining her personality. Levertov was clearly a person of huge intelligence and artistic talent, with an immense capacity for literary output (she published about 30 books of poems, essays, and translations). Yet it appears that Hollenberg is so loath to “sit in judgment” that we left to infer that Levertov had a mean streak, a way of quarreling with people, losing old friends and even family members, and that she was inclined to be arrogant and self-centered. She was estranged from her only sister and even from her son for years. Hollenberg would not venture to say, “She could be hell on wheels,” although she gives enough examples for us to guess as much. In 1978, Levertov resigned a full-time, tenured position at Tufts in a snit over her intractable opposition to the hiring of a candidate for professor of poetry. A similar battle took place at Stanford a few years later. One wonders how she gained the nickname at Tufts (not in the book) of “Disease Levertov,” but a 1978 scene that Hollenberg witnessed, where she cruelly berated a student and told her—in front of others—that she didn’t belong in graduate school, gives us an idea.

Only late in the book, on page 356, does Hollenberg turn directly to these traits, notably Levertov’s “formidability to the point of intransigence.” Even here, she has Levertov reveal the details. The poet “recognized this quality in herself, and as she grew older, she regretted deeply the ‘pride and hardheartedness’ that too often over the years had driven people away. The result was profound loneliness. As she wrote in her diary in 1984, Mitch had made her feel cherished in the beginning, as had her mother before him, but before long criticism became the prevailing tone of their marriage.”

She was also somewhat snobbish, which would have put off some people; almost everyone in her life is an artist or intellectual. Even her interest in politics is on an elevated policy plane. She speaks and writes poems for peace and justice, but one can’t imagine her making phone calls, stuffing envelopes, or holding a sign for a reformist local politician. That would be too gritty; probably no poetry in it. Again, we suspect this, but Hollenberg allows Levertov to articulate it: “When she thought about [Archbishop Oscar] Romero’s exemplary love of the poor, she had to admit that she didn’t truly share it. With characteristic integrity, she wrote, ‘I really am an intellectual snob, I guess, and I like to be with people of refined manners and developed minds.’”

In the late years of her life, as part of as a process of spiritual conversion, Levertov tried to remake her usual treatment of some (not all) other people. She faced up in sorrow to all that she had given up in trying to be a figure of greatness who expected others to meet her high standards and emotional needs. Yet here too there was a certain lack of proportion. The year before Levertov died, she wrote an essay of regret that she had once berated Jean Rankin Parker, a childhood friend, when they were about 10 years old, sundering their friendship for years. She faxed the text to Rankin, who was on her deathbed, hoping to be forgiven. To her relief, she was.

This biography is the labor of many years and of deep reflection and care. Most of my quibbles are not worth mentioning, except for one: The artwork is poor; Some of it is gratuitous, while surely, given her very public career, there are more extant late images of Levertov than are reproduced here. One of the blurbs calls the book “long-awaited,” which sometimes means the publisher was almost in despair at getting the manuscript. For lovers of Levertov and students of her poetic era and its vast crowd of characters, it will be worth the wait. The person at the center, even with all her brilliance and gifts and achievements, never ceases to be at her core a poignant, lonely, insecure little girl. But the edifice of beauty that she built is secure indeed.

David Mehegan is a contributing writer.

Tagged: A Poet's Revolution: The Life of Denise Levertov, American, Denise Levertov, Donna Krolik Hollenberg

A pleasure and an education to read.