Book Review: “The Melancholy Art” — Art History and Depression

If I suffered half as much from the thought that most art has been lost as I suffer every day from the recollection of departed family and friends, I would be in a mental hospital. In this sense, I found myself resisting the message of The Melancholy Art, to the point that I felt that the book was laying a guilt trip on me.

The Melancholy Art by Michael Ann Holly. Princeton University Press, 224 pages, $24.95.

By Gary Schwartz

Thirty years ago I found myself searching for conceptual tools to further the historical study of art. Some works of art—a small minority, a point that is often forgotten—have survived from the past, and some of those—a small minority of that small minority—are considered to be the worthwhile kind of object that we put in museums, pay millions for in the market, and single out in textbooks as key monuments. This process—the formation of canons and the privileging of its objects—provides us all with delight; every lover of art is endlessly grateful for that store of masterpieces. However, these same practices have a distorting effect on our historical understanding. They insert present-day judgments into historical reconstruction at a far too high level. When we have placed our chosen objects into their periods and connected the dots, what we get is too much a retrojection into the past of our own aesthetic preferences and art-world hype. In order to practice an art history that respects the value systems of the times and places in which the objects of study were created, we have at least to try to play down our own preferences.

This seemed to me so self-evident that I grew increasingly discontented that the field of art history continued to be run, by and large, on the opposite assumption. One forerunner of the preceding generation who put this standpoint into words was I. Q. van Regteren Altena. In his inaugural lecture as professor of art history at the University of Amsterdam, delivered on October 11, 1937, he said,

As far as history is concerned, I dare say, it differs fundamentally from art history. This is not hard to explain. A so-called historical fact is a priori indeterminate; it takes on form only in the mind. But the manifestations of the world’s drive toward visual art are realities: churches or statues, imagines factae, immutabilities.

How useful, I thought, to have a statement that formulates so clearly the opposite of what I believe. To my mind, “the manifestations of the world’s drive toward visual art,” in their physical history as well in shifts of fashion, are anything but immutable. In terms of immutability, historical facts that can be triangulated through documents, first-person testimonies, and evidence on the ground come closer to it than works of art.

Consider my feelings, then, when I opened Michael Ann Holly’s new book and read the first words of the preface:

Every discipline of the humanities possesses a soul that rests quietly at the heart of its fascination with times gone by. . . . the history of art differs in one distinct way from the other historical ‘sciences’ . . . My argument is that the ‘specialness’ of the history of art resides above all in the material objecthood and presence of its artworks.

Nor could I help comparing two other ideas in these writings. Van Regteren Altena: “Can it be that the insufficiency of the word as a means of expression lies at the root of the artist’s dissatisfaction with art history (kunstwetenschap), which . . . obliges me to ask in what way its practitioners have fallen short of their aim?” Holly: “Writing about art. What is it? Why do we do it?. . . As so many of us discover, it is the process of writing, indeed the very language we use as a means of preserving the past, that comes to be implicated in the loss of original meaning.”

The attitudes articulated by both scholars are not theirs alone. Nor are they really “arguments.” They are statements of allegiance to a particular side in a conflict smoldering under the surface of the field. What van Regteren Altena and Holly share, across the decades, is a distaste for what they see as overintellectualized art history, “a research protocol devoid of sentiment,” art writing that closes itself off from what Holly calls “the experience of visual captivation.” She takes regular jabs at positivists, empiricists, and historicists. Not all of them are fair. She tends to equate these disciplinary choices or temperamental inclinations with soullessness.

In her closing call for more “affective pleas” she writes, “Open wonder about what we cannot know, even what we cannot see, might release writers on art from their weighty chains of professional responsibility and the use of a rhetoric born of traditional scholarship and curatorial initiative.” All of us, I’m sure, would like to read better, low-jargon writing, but this appeal—by the long-time director of a major art-history research center, the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA, no less—poses uncritical “wonder” or “captivation,” reflexes over which we have no control, against “professional responsibility,” and chooses for the former. The question arose that I asked myself quite a lot reading The Melancholy Art: can she really mean that?

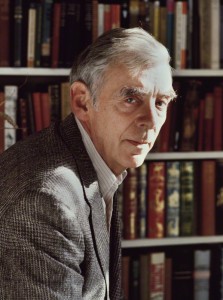

The late Michael Baxandall — his was a fundamentally postmodernist point of view. Photo: Max Whitaker

These issues take on particular relevance in the chapter on the late Michael Baxandall (1933–2008). Holly saw him as a natural ally in her campaign of the latter twentieth century to revolutionize art history through a massive dose of critical theory. “Baxandall’s is a fundamentally postmodernist point of view,” she writes, so that she is disappointed and irked by “the perplexing irony” that he adopts a “very low and simple theoretical stance” and that he felt that “the discipline of art history is destined to remain forever ‘sub-theoretical.’” Personally, I agree with Baxandall, for a reason that is not considered by Holly. That is, once one subverts the pretence of objectivity in scholarship, there is no stopping point between that and sheer Pyrrhonian skepticism. (“Nothing can be known, not even this.”) In philosophical terms, there is probably more to be said in favor of Pyrrhonism than of the scholarly project—or the scientific one, for that matter (Richard Feynman: “We never are right; we can only be sure we’re wrong”). However, in order to get through life, or even through the day, we need the presumption that we are as closely in touch with the truth as circumstances allow. Those circumstances, to most art historians, include the framework of the discipline as they inherited it.

The tension between wonderment and reductionism, between direct experience and the creation of distance, may rest at the heart of Holly’s book, but the great subtheme that carries it along is her diagnosis of art history as a melancholy pursuit.

The compelling visuality of the work of art resists appropriation by either the cleverness of historical accounts or the eloquence of descriptive language. Something remains; something gets left over long after explanations are exhausted. Consequently, I have been arguing, the discipline is constitutionally fated to suffer from a quiet melancholy malaise.

Holly uses the idea of melancholy as a magic wand. Wherever she waves it, everything turns out to be tinged with sadness, loss, unattainability. This goes well beyond the practice of art history. In one of the many touching vignettes in the book, one that the reader in Boston will not want to miss, Holly writes a pocket appreciation of Isabella Stewart Gardner and her museum.

Her life was full of contrasts, but perhaps none more searing than the death of her young son, John Lowell Gardner III (Jackie) in March of 1865, not long before his second birthday . . . By contemporary accounts, Gardner suffered an enervating depression that could only be mitigated by a change of scene. . . . Her first purchase of a work of art took place in Spain, predictably of a mother and child, a Virgin and Baby Christ attributed to Francisco de Zurbarán . . . Nearly two decades ago, I was struck by the preponderance of the subject of the Madonna and infant Christ on view in nearly every room and came softly to savor the sweetness and sadness of the collection as born from the child she had long since lost.

This is a lovely soliloquoy, well-informed and sensitive, of which the reader is treated to many more in The Melancholy Art. Less successful is the segue to that other kind of loss, the infamous robbery in 1990.

. . . When this founding loss at the beginning of the century became compounded by the bold theft at the end of it, it threw into sharp relief this particular museum’s role as a dramatic enactment of melancholy with which physical spaces in any museum can encircle the works of art they wish to keep intact and present.

The multiplicity of loosely joined concepts and associations in this poor sentence shows Holly overextending herself. The relation between “this particular museum” and “any museum” is not thrown into sharp relief but muddled. What is being said about the relation between Jackie’s death and the theft? Is there any meaning at all in the rephrased statement “The physical spaces in any museum can encircle with a dramatic enactment of melancholy the works of art they wish to keep intact and present”? Most of Holly’s prose is elegant and full of surprising, well-written turns; too bad that The Melancholy Art is marred by sentences like the above. Accepting the role of the pedantic critic, I quote one more, as an admonition to the editors of the Princeton University Press series in which this book appears, following Leonard Barkan’s Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures, which also suffered from occasional literary bloating: “The actual physicality of objects that have survived the ravages of time in order to exist in the present so frequently confounds any typical art historian who retroactively sets out to turn them back into past ideas, social realities, documents of personality, but in Stokes’ case, his retroactivity extends as far backward as ‘the action of wind on water.’” I’m not convinced that this is an English sentence, but even if it is, it does no good for a book that takes the author’s colleagues to task for overindulging in rhetoric.

Since The Melancholy Art addresses the reader, especially the art-historian reader, in rather personal terms, let me close by bringing my own feelings into the discussion. The melancholy I have experienced during the past 50 years of my life as an art historian is hardly related to art, let alone art history. If my professional work truly brought with it a psychological condition related to depression, I would not have been able to continue doing it. If I suffered half as much from the thought that most art has been lost as I suffer every day from the recollection of departed family and friends, I would be in a mental hospital. In this sense, I found myself resisting the message of The Melancholy Art, to the point that I felt that the book was laying a guilt trip on me. “Words about images that struggle to offer a powerful cure, as much as they are a regrettable demonstration of inadequacy, are those that make some kinds of art history writing survive, while others quietly fade away.” In my art-historical writing, I have tried to avoid unequal struggles with subjects to which I cannot do justice, nor have I pretended to sell my readers powerful cures. I see nothing wrong with this, and I do not believe that because of those choices I am necessarily on a fast track to oblivion.

Only in one four-word phrase did I feel spoken to in my emotions. It comes in a discussion of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment, in a dense but wonderfully engaging chapter on Jan van Eyck and Vincent van Gogh as well as Jacques Derrida, Martin Heidegger, Meyer Schapiro, and Melanie Klein, among others. In a throwaway line, Holly says that Kant’s Critique can be read as an “’apology’ for what cannot be articulated, namely, the experience of the sublime in nature, the unspeakably beautiful in art.” Now there—in the sublime in nature—I am overcome day by day by melancholy. I experience all of nature as sublime, and to the regret of my wife, the master of a magnificent garden, I suffer attacks whenever I try to muster sufficient appreciation of even the most modest leaf or stem. Looking at those incomparably beautiful forms is incapacitating enough, but when I then add the awareness that they are living things, pumping fluids and current and foodstuff as I watch, filling an ecological niche that takes in my entire physical environment, I go weak in mind and morale as well as in the knees. If Michael Ann Holly or other colleagues are really hit that hard in the museum, they have all my sympathy.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book(2006).

His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly.

In November 2009, Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

He is a member of CODART.

Responses always welcome at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl.

Tagged: Michael Ann Holly, Princeton University Press, Schwartzlist