Film Interview: “Secundaria” — Learning the Art of Ballet in Cuba

UPDATE: Secundaria will screen this Friday as part of Boston University’s Cinematheque series. Friday, September 13, 7 p.m. at Boston University, COM, Room 101, 640 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA.

Ballet program administrators in Cuba will be happy I’m telling the true story in Secundaria, the one they’re not allowed to tell themselves.

Secondaria. Directed by Mary Jane Doherty. Screening at the Independent Film Festival of Boston at the Somerville Theater, Somerville, MA, April 27, 1 p.m.

By Bill Marx

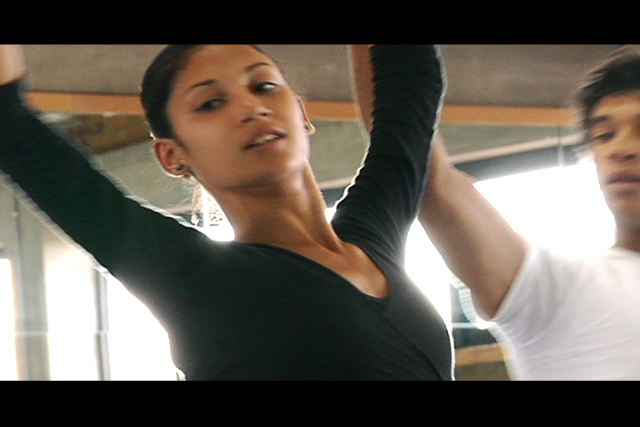

The documentary Secundaria, receiving its world premiere at the Independent Film Festival of Boston, focuses on the trials and tribulations of Cuban high school students attending their country’s renowned National Ballet School. The film chronicles the artistic and social challenges for the pupils and the institution, moving from a sensitive examination of the physical and creative demands of dance to a more dramatic study in political repression and personal choice. One of the young dancers, Mayara, makes a momentous decision about her future, defecting to the United States while the troupe is on an international tour. Secundaria records the shockwaves sent among the girl’s family, friends, and teachers.

Since 1990, Secundaria director Mary Jane Doherty has been an Associate Professor of Film at Boston University. She helped develop B.U.’s Narrative Documentary Program, an approach to non-fiction storytelling that uses the building blocks of fiction film. I spoke to her about the obstacles raised by filming in Cuba, whether she assisted Mayara’s defection, and the significance of the documentary’s title.

Arts Fuse: Talk about the impulse behind the making of Secundaria. What attracted you to telling this story?

Mary Jane Doherty: Back in 2006, I read a short clip in the NY Times, something about “Fourteen Cuban Ballerinas defecting.” It struck me in a flash: Whoa! Beautiful bodies, Latin rhythms, decaying pastel plastered walls—the sound and visuals are in place already! The movie will walk itself into my lens. Indeed, that’s sort of what happened. . .

I was extra-raw from working on a cerebral, non-visual film, if there is such a thing, so I was particularly adamant about finding a story with sensual elements at its base.

AF: How much knowledge about dance does this film ask of the viewer?

Doherty: This film asks for little knowledge of ballet but requires a strong sensibility for music and sound in general. I think of the viewer as someone like me, a naive and romantic first time visitor to Cuba with a vague sense of the importance of classical ballet. The idea—the engine of the movie in fact—is that we, the audience and I, go on a journey together and eventually supplant our romanticism with the gritty truth. We end up loving the place and the people but now our love is based on something rich and deep.

AF: There is a minimum amount of social and political context in this film, though from time to time you raise issues of poverty and lack of resources, and issues of race and class are mentioned in the epilogue. Why did you decide on this approach?

Doherty: From the very beginning I had only one goal—to focus on those visual and aural moments that could not be told in words. I wanted to convey what it feels like, on a visceral level, to be out there on the dance floor. So, when filming, I turned my head off, then fell in love with my characters by looking and listening to them through the viewfinder; the composition in the frame followed. That’s it. I am not promoting this approach over others, just identifying my one skill (besides parallel parking).

The idea is that social and political issues percolate up through the seams of the film, and through the characters’ point of view. The politics are there but not evident until two or three days after watching the film.

AF: How do you see this film as contributing to American/Cuban relations?

Doherty: On an immediate level, Secundaria makes little contribution to American/Cuban relations.

I know the ballet program administrators in Cuba will be happy I’m telling the true story, the one they’re not allowed to tell themselves.

But, this movie is by no means The Thin Blue Line or Inside Job. It was never to be. There’s a large audience of journalists and Very Smart People who may see this as a missed opportunity to tackle the politics head on and provoke real and immediate change. The catch is that I didn’t shoot that film. However, I will write a book.

AF: What were the challenges of filming Secundaria in and out of Cuba?

Doherty: Even though I traveled legally to Cuba, it was still a challenge getting in and then getting back out—with my nerves and equipment all in one piece. It’s Cuba; you never know what’s going to happen. Each time I went through customs, one more protective veil of naiveté dropped away until, as I got to the 21st trip—the last and most crucial trip—I sent such strong fear pheromones that the customs agent pulled my passport and camera. The agent stared at me, his eyes ice cold, “You are not a tourist.” (It was a trick to get my gear and passport back. Long story. I do need to write that book.)

AF: How surprised were you by Mayara’s decision to defect to the US? Did you help her in some way?

Doherty: I was so shocked I could barely hold the camera upright. There I am at the airport, glommed on to the image through the viewfinder as usual, filming “my” dancers parade through the airport arrivals door. Then arrivals door shuts. I look up and realize suddenly—Mayara’s not here. I had one of those classic full body blood draining sensations. But, somehow, kept it together enough to continue filming.

Which, answers the second part of your question.

AF: What is your main concern with how the audience will receive your film?

Doherty: Through several rounds of critique sessions, I’ve had people question whether I set any scenes up. Most “competition” films are shot backwards; the filmmakers film “the winners” and then film interviews after the fact and weave that material into the set up section of the movie. This is legitimate and, in a practical sense, almost the only way to film these kinds of stories.

And, yet, with Secundaria, I happened to pick the one dancer in the very beginning who made the boldest move. Sheer accident! So, I want the audience to TRUST the journey we go on together since it’s essentially the engine of the story.

AF: Why do you call your movie Secundaria?

Doherty: As it turns out, I shot footage for two films while down there. This year I will finish editing the other film, about three, eight-year-old dancers working their way through the system. This film will be called Primaria. There’s a pleasing symmetry to the titles.

Also, Secundaria, which means “High School,” is a quiet homage to Frederick Wiseman’s famous film although, it’s true, our approaches to film storytelling are not quite the same. And, finally, it’s a pretty word.