Food Muse: Happy National Donut Day!

Musings on the history, shapes, and ubiquity of donuts on the occasion of the holiday.

By Sally Levitt Steinberg

National Donut Day (the first friday in June) falls under the sign of Gemini, the sign of divided souls, and so it is not surprising that the donut leads its own divided life. We love ‘em, we hate ‘em, we love to hate ‘em. The donut is beloved and vilified, old and new.

Who invented the donut?

We all did, everyone. All societies since the beginning of time have had a sweeetened, fried cake. They have been found in every culture, from the ancient Near East to China to Italy. Donuts are old, as old at least as the Bible, where they are mentioned as cakes fried in oil and sweetened with honey (Leviticus). Whether they are called ciambelli, Italian for tires, or sufganiyot, the Hebrew word for Chanukah donuts, or olykoeks, the Dutch word for the donuts Washington Irving described on the tables of the Dutch settlers in his fanciful history of New York, they are donuts.

In France one name for them is Pet de Nonne, Nun’s Fart. On a feast day a long time ago, a novice nun was dangling her ball of dough over hot oil when a curious noise like the trembling of an organ issued from beneath her habit. Was it the devil? Mais non! It was the lily white nun, who turned red as a strawberry. An attendant group of tittering angels tried to stifle the noise, but it was too late. The dough dropped into the oil and bloomed and swelled into a miraculous golden globe, a delicious dessert named Pet de Nonne after the hapless novice.

Donuts are war heroes—they saved the morale of soldiers in World War I when it had rained for a month. The Salvation Army “lassies” fried donuts in helmets and cut them with shrapnel, and because of them the soldiers went from glum to happily gluttonous. These donuts became a symbol of the soldiers and of the Salvation Army. They were so popular that airplanes lifted them from trench to trench. This was the origin of National Donut Day, which began in honor of these Salvation Army wartime donuts. Forever after donuts were linked to the Salvation Army as its symbol and to soldiers in wars, often called “doughboys.”

Donuts are matter and anti-matter. Was the donut there first, or was the hole hanging in the air waiting for the donut to make its way around it and define it? The inventor of the hole is thought to be an American whaling captain from New England, Captain Hanson Crockett Gregory, who was caught with a donut in a storm and slammed it on the ship’s wheel to give birth to the hole in the donut in 1847. Defenders of his claim to this brilliant stroke won out in the Great Doughnut Debate of 1941 in New York’s Astor Hotel over the defender of an Indian who shot a hole in a donut with his arrow as a pilgrim maid dropped it into bear fat.

But this is subject to doubt. There’s a 17th-century, Dutch/Spanish painting in the National Gallery, a still life with a donut with a hole.

Juan van der Hamen y León, Still Life with Sweets and Pottery, 1627 Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.75

Donuts are poor and rich. They have been called the Poor Man’s Rich Food. They saved many from starvation during the Depression, when they were handed out in donut lines like the famous bread lines. They saved lives. When they first became popular, they were thought of as healthy, a cake of milk and eggs and flour, until they became unhealthy, as repositories of fat and sugar and other evil demons of dietary incorrectness. They went on to put our waistlines and health at peril as they jumped from home fires to assembly lines. But not before they made it into Dr. Crum’s Famous Donut Reducing Diet, 1941—donuts before each meal.

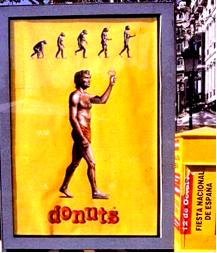

They are the villains constantly used to represent bad American eating habits. When the subject of junk food arises, the donut is its most common image. They made the cover of The New York Times Magazine juxtaposed with an apple, the symbol of health.

But strangely, their numbers never diminish. They keep on “a comin’ and a comin’ and a comin,’” as Homer Price said in the book by Robert McCloskey when his machine wouldn’t stop spewing donuts. People are not going to stop eating them, in spite of all warnings. Americans eat 10 billion a year, and that doesn’t count other countries, where passions run high. The Japanese are nuts about American donuts. Recently New York’s famous Doughnut Plant, a Lower East Side shop specializing in natural/organic donuts with cashews and rose petals, opened a beachhead in Japan, where donuts with yuzu and shiso, a savory leaf, are made. Dunkin’ Donuts and Mister Donut are very successful in Japan—one of the Dunkin’ Donuts shops in Japan sold the greatest number of donuts of any of their shops around the world.

Donuts are also one of our national good will talismans, used for patching quarrels and fostering conciliation, a sine qua non at political rallies and church suppers and school meetings. Even Hillary used them as a campaign enhancer.

Donuts are considered American, but they are not. They originated everywhere, but they are one of our most potent national symbols. Were the first donuts on these shores made by Native Americans, who fried one that was later found petrified in a burial mound out west, or were they brought here by the Pennsylvania Dutch or the pilgrims of New England? The petrified donut proved it a native, and the discovery of the hole off American shores by a whaling captain gave an American identity to the donut with a hole. When Captain Gregory’s donut emerged with the distinctive ring shape, it went on to gain life as an American symbol. This was magnified and multiplied by the invention of the donut machine in America after World War I. Before the machine, donuts were handmade and few in number. The machine manufactured them for the first time and spread them from the frying pan or kettle into the donut shop and supermarket in numbers unimaginable before.

My grandfather, a poor Russian immigrant, an orphan who grew up selling newspapers in brothels in Milwaukee before he knew what brothels were, was working in a bakery in Harlem when the soldiers came back from World War I wanting the donuts the Salvation Army women had made. On a train he met an engineer, and together they worked on 12 or 13 machines and got one that worked. He put it in the window of his bakery and waiting lines grew and grew. He put it in Times Square and it stopped traffic in New York. The donut business was born.

What’s in a donut apart from ingredients? Donuts are circles, the elemental shape in nature and culture. They are the shape of the universe, the torus, which is a donut, and they are also the shape of its smallest particle, the nucleus. They are all over our bodies and all over the animal world—consider the raccoon’s eyes—and all over the sky—Saturn’s rings. It’s their shape that makes them what they are, not just any old sweet. Donuts can morph to become part of science and art and even urban planning—cities are often described as donut-shaped, ring-shaped around a center. Their life as metaphor is ongoing. They are used to describe a health insurance feature, The Doughnut Hole. They are even used to define bagels as “donuts with a Jewish education”.

The circle is symbolic and resonant with meaning, and that’s how donuts got to be symbolic and different from other sweets. Anyone can make a cake, but you can look through or twirl or ruminate upon a circle, or use it as prototype for shapes in the cosmos. Would eating a donut have the same quality, something lifting it above just food consumption, eating, if it was just a cake in any old shape? There is a subconscious element to the eating of a ring-shaped cake. It appeals to our collective unconscious and its associations with circles. A simple idea, a genius application.

Donuts are old, and they are new and ever renewed. Not only are they sold in the billions by state-of-the-art shops and chains—Japanese shops in America even have Japanese donuts in red bean and green tea flavors—but they are now on dessert menus in fancy restaurants. The newest new dessert is a gussied up, fancied up donut. The Boston Cream donut has traveled south to New York, where it is served at Craft restaurant in an elegant incarnation made of brioche dough, with cheesecake ice cream, brittle, and malted milk. Then there’s the Thomas Keller donut, a most beautiful orb Frenchified as Boston Crème, a cream-filled, chocolate-topped donut, decorated with multicolored snap-crackle-pops.

Although it may not have been the first American donut, the Massachusetts state donut is certainly among the best. What is it? The Boston Cream donut, of course.

The fanciest? Could be Chef Mavro’s Hawaiian Lilikoi (passion fruit) donut with guava coulis.

The weirdest? Possibly the cheeseburger donut by Krispy Kreme.

Best in Boston? My vote goes to Ziggy’s in Salem for their amazing, homemade taste and light texture.

The worst anywhere? My pedigree prevents this from being published.

The funniest? Mark Isreal’s Yankee pin-striped donut—sorry, Red Sox.

Most useful financially? Mark Isreal’s gold-iced donut.

Sexiest? Tajikistan’s vagina-shaped donut.

One of the best things about donuts is that they tell stories, unlike other foods that are just food. The donut gives off vibes of America and soldiers and truck stops and the prairie and city streets. When you eat one, even if it is in an elegant eatery, it still carries with it the baggage of its associations and connotations. That makes it better than just some rogue creation by an inventive chef.

Where there’s a donut, there’s a story. Donuts are U. S.

Mmmm donuts, says Homer Simpson.

Where would we be without them?

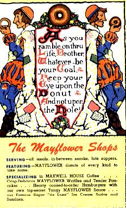

My grandfather’s motto, which he used in his Mayflower Donut shops, and which became famous, was:

As you ramble on through Life, Brother,

Whatever be your Goal,

Keep your Eye upon the Donut

And not upon the Hole.

===========================

Sally Levitt Steinberg is a writer, journalist, and oral/personal historian. She has written several books, including The Donut Book, the world’s definitive book of everything-you-need-to-know about donuts. It was chosen twice as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, it has been featured in all the media, including NPR, the Martha Stewart radio shows, and the film “Donut Crazy” for the Travel Channel, and its materials form The National Donut Collection at the Smithsonian Museum.

She has written a biography, The Book of Joy, as well as several personal histories and a book on interior design. Her essay, “Coffin Couture,” was cited as the best piece in the recent anthology of personal history, My Words Are Gonna Linger. She has written articles for many publications, including The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and The New Yorker. She lives in Boston.

Order The Donut Book through the link below to Amazon and The Arts Fuse receives a (small) percentage of the sale.

Wonderful piece! So I went to Amazon to look at the book, and guess what advertisement came up beside the customer reviews? “Diets Don’t Work. Weight Watchers Does.” Sigh. I favor the chocolate honey-dip and French cruller from Dunkin’, myself, but hard to bring myself to eat them. Fun to read about, though.

Super informative, charming piece of Americana!! Loved it.

Since I write about people who often didn’t know where their next meal was coming from, this happy post (and funny poster) reminded me of how much of life’s joy is…donuts! (food).