Book Review: Jane Austen’s “Emma” — Aptly Annotated

Editor Bharat Tandon guides us expertly through “Emma,” stopping along the way to augment the text by clarifying usages, concepts, and references that may stump the 21st-century reader.

Emma: An Annotated Edition, by Jane Austen. Edited by Bharat Tandon. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 576 pages, 119 color ills., $35

By Evelyn Rosenthal

How can you love a novel about a heroine so spoiled, oblivious, and self-deluded that one of the best films based on it describes her, perfectly, as Clueless?

Simple, if the novel is by Jane Austen: you just revel in the brilliance of the characterizations, the witty dialogue and satirical observations, and the pleasures of a plot fueled by gossip, misunderstanding, mystery, and romance.

Of course, I’m talking about Emma. In the famous opening paragraph of the 1816 novel Austen describes her heroine and sets up the story in the pithiest of nutshells: “Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her.” Instantly we learn who she is, that things aren’t what they seem, and that Emma’s about to become acquainted with trouble. By the end of the first chapter, we surmise that the trouble will be of her own making, as everybody’s favorite Regency-period yenta embarks on a series of misguided matchmaking adventures. By the end of the book, we applaud the rueful, more self-aware Emma her troubles have created.

According to Bharat Tandon, editor of Belknap Press’s sumptuous new annotated edition of the novel, Emma is “a story about the world, individuals’ interpretations of it, and the perpetual difficulty of distinguishing between them.” And if the novel’s characters have a hard time making sense of the world and their skewed views of it, modern readers can be even more puzzled, observing that world at a remove of two centuries. While it’s true that generations have read and enjoyed Austen’s novels without the aid of notes, the in-depth annotations and delightful illustrations of Harvard’s annotated Austen series draw the reader even more intensely into the world of the characters and their creator. As Robert Morrison did so splendidly in the recent Persuasion: An Annotated Edition (see my Fuse review), Bharat Tandon guides us expertly through Emma, stopping along the way to augment the text by clarifying usages, concepts, and references that may stump the 21st-century reader.

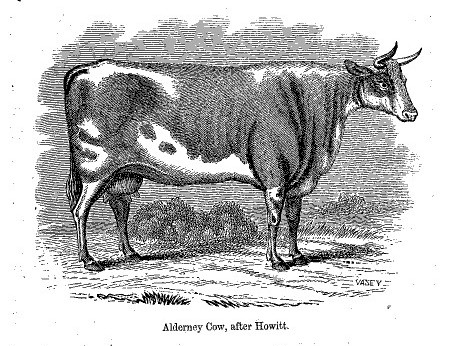

The Alderney cow, a breed popular in Austen’s time. From George Vassey, A MONOGRAPH OF THE GENUS BOS (London, 1857).

The story unfolds in and around the rural village of Highbury—a fictional site in Surrey, Tandon points out, that stands in for no real place, as its various distances from locations mentioned in the novel conflict with one another. Emma lives with her hypochondriacal father—fond of gruel, terrified of drafts—at Hartfield, a small estate dwarfed by nearby Donwell Abbey, whose owner is the forthright family friend and in-law Mr. Knightley, brother of John Knightley, the barrister husband of Emma’s sister Isabella. When her governess and close friend Miss Taylor marries another gentlemanly neighbor and becomes Mrs. Weston, Emma decides to amuse herself by finding a wife for Mr. Elton, the handsome young vicar. She fixes on Harriet Smith, a pretty but naïve young boarder at Mrs. Goddard’s school, the “natural” (meaning “illegitimate”) daughter of an unknown benefactor. Emma, fancying that Harriet’s father might well be a gentleman, befriends her and proceeds to “form her opinions and her manners,” talking her out of a marriage proposal from the sensible, honorable farmer Robert Martin, and into falling in love with Elton. Needless to say, all does not go well.

Tandon’s excellent introductory essay and enlightening notes, observations, and weavings in of pertinent Austen scholarship enrich and deepen the story. The Oxford English Dictionary makes numerous appearances, as does the dictionary of Samuel Johnson, one of Austen’s favorite authors. Tandon includes contemporary recipes for everything from Mr. Woodhouse’s favorite watery gruel to gingerbread, baked apples, and spruce beer (a kind of root beer). When Harriet chatters on about her idyllic summer with the Martin family and their “eight cows, two of them Alderneys,” Tandon notes the breed’s popularity at the time “both for its decorative qualities and for its high yield of rich milk,” cites appearances in Smollett’s Humphrey Clinker and in a letter from Austen’s mother about the family’s own Alderneys, and gives us a charming engraving. Lovely illustrations by James Sowerby and George Brookshaw depict the varieties of strawberries Mrs. Elton mentions during one of Austen’s great humorous set pieces, where, through snippets of speech, we see her go from near-hysterical delight to crabby exhaustion during a summer strawberry-picking excursion.

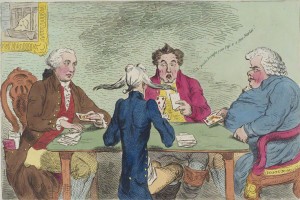

Paying attention to such details is not just entertaining; it also lets us in on what Tandon calls “Austen’s subtle intimations of social relations through objects.” The Blue Stilton and North Wiltshire cheeses served by Elton’s friend Cole mark the younger Highbury residents as “part of a more modern economy of commodity consumption,” where improvements in transportation have allowed well-heeled buyers to obtain products from all over England. The games people play—backgammon, riddles, charades, cards—likewise add nuance to characterizations: Mr. Woodhouse and his friends favor quadrille, a card game out of fashion by 1814, while the younger members of Highbury’s whist club, such as Elton, are “in touch with the latest metropolitan activities.”

As is inevitable when annotating an Austen novel, where reading itself is a subject and characters are defined by what they read (or, as Mr. Knightley says of Emma, what they “mean to” read), Tandon comments on authors—Shakespeare, Thomas Gray, Walter Scott, Oliver Goldsmith—cited (and sometimes recited) by the novel’s characters and referred to in Austen’s personal writings. Here the book’s illustration program, which included images of the author of each passing reference, seemed a bit overeager. I really wouldn’t have missed the photo of a Wedgwood bust of Seneca supplementing a note on his possibly having coined the maxim “virtue is its own reward.” But illustrating Emma must have been harder, I suspect, than it was for Persuasion, both because it’s much longer, and because the action pretty much stays put in fictional Highbury and doesn’t wander off to the picturesque, historical settings of Lyme Regis and Bath, where much of Persuasion takes place. There are some wonderful finds, though: a facsimile of an Austen family letter showing “crossing,” where the writer fills a page, then turns it and continues writing at right angles, to save paper, and thus postage; and a page of music manuscript in Austen’s hand from Chawton Cottage, her final home, now a house museum.

James Sowerby, FRAGRARIA ELIATOR: HAUTBOY STRAWBERRY, one of the varieties Mrs. Elton mentions during the strawberry-picking excursion. From AN ENGLISH BOTANY (London, 1790–1814).

If the subjects of the annotations in Emma are more quotidian than those in Persuasion, that’s because the novel itself stays in the realm of daily life in the close-knit rural community. The characters and setting of Persuasion require delving into the history and politics of the Napoleonic era and the British navy; in Emma we get only an oblique reference to the slave trade, when the narrator describes Elton’s fiancée Miss Hawkins as the daughter “of a Bristol—merchant, of course, he must be called.” In an extensive note, Tandon argues that while Austen’s novels have been accused of ignoring contemporary politics, she relied on the “shared body of background knowledge” of her contemporary readers to convey political meaning without spelling it out. The “typographical flinch of the long dash” before naming Miss Hawkins’s father’s profession hints that “something isn’t being said”; that something turns out to be an association between the southwestern seaport Bristol and the slave trade—a link so close the city’s name would have signaled the connection. Tandon goes on to discuss the debate in Austen scholarship about the presence of slavery in the novels—maybe not a major concern for the legions of Austen lovers that have made her a rock star of English literature, but a legitimate academic question, and the kind of intriguing observation that this Emma and the other entries in the Harvard annotated Austen series do so well.

While Emma herself is not my favorite Austen heroine, her evolution from charming but self-deluded to charming but chastened and thoughtful has always made for an entertaining and satisfying comic journey. Reading her story in this annotated version that spotlights the meanings and materials of her—and Austen’s—world makes this great novel even more appealing.

Tagged: Bharat Tandon, Emma, Emma: An Annotated Edition, Harvard University Press