Book Interview: Literary Crusaders of The Gilded Age —Tackling the Great American Railroad

The Great American Railroad War reminds us of an inspired journalistic reaction to the crimes of an earlier age of robber barons.

By Bill Marx

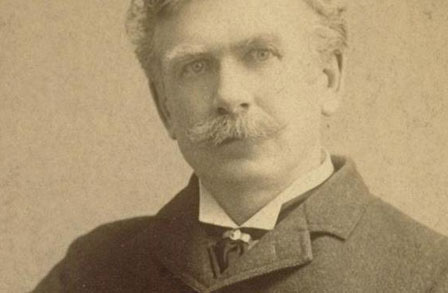

I have been on a bit of an Ambrose Bierce binge over the past few months, beginning with the recent publication of a Library of American volume dedicated to his writing, which contains a generous helping of his short stories, The Devil’s Dictionary, and memoir material, much of the latter focused on his experiences as a combatant in the Civil War. Based on that reading, I highly recommend an immersion in Bierce, if only as a refreshing dip into a polemical strain of contra-American optimism that links the critical iconoclasm of Edgar Allan Poe and H. L. Mencken.

I was writing my essay on Bierce for the Columbia Journalism Review when I received a galley of a book that explores Bierce’s impressive talents as a journalist, which are not as represented as well as they should be in the Library of America collection. Bierce’s deserved reputation as a master of vituperation, which made him a celebrated and reviled newspaper columnist on the West Coast in the late nineteenth century, has overshadowed an occasion when his genius for vituperation was put to unusually important use: to drive a newspaper’s investigative expose of the crimes of a big business giant. Bierce created some of the finest American journalism of the century when he put his savage venom at the service of a successful campaign to reveal corporate and government corruption.

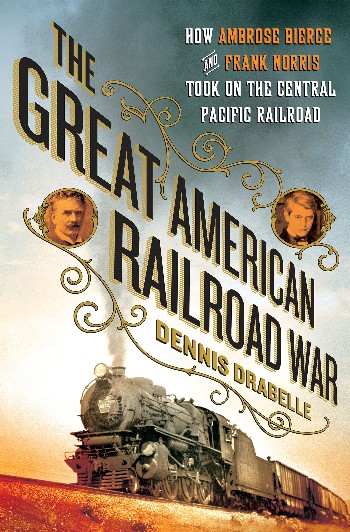

I ended up reviewing The Great American Railroad War: How Ambrose Bierce and Frank Norris Took on the Notorious Central Pacific Railroad (St.Martin’s Press, 306 pages, $26.99) for the Columbia Journalism Review. The volume highlights the galvanic highpoint of Bierce’s career as a muckraker—he was dispatched with a team of reporters by publisher William Randolph Hearst to Washington D.C. in 1896 to stop the efforts of the monopolistic, congressman-bribing Central Pacific Railroad to renege on federal government loans (which were used to subsidize construction) that totaled around $75 million. Bierce wrote over 60 articles for the San Francisco Examiner—their blend of deft, satiric humor and dead-on revelation of skulduggery bore fruit, at least to the point that the Central Pacific Railroad backed off from its attempts to duck its obligations. Novelist Frank Norris was also memorably animated by the perfidy of the Central Pacific Railroad in his 1901 novel The Octopus, which remains a touchstone of compelling fiction that crusades against corporate misdeeds.

Drabelle provides hunks of Bierce’s columns, and they are a delight to read today, such as this description of the nefarious railroad mogul C. P. Huntington testifying before Congress: “Mr. Huntington is not altogether bad. Though severe, he is merciful. He tempers invective with falsehood. He says ugly things of his enemy, but he has the tenderness to be careful that they are mostly lies. So Mayor Sutro may reasonably hope to survive Mr. Huntington, though Mr. Huntington’s rancor blown about in space as a pestilential vapor will outlive all things that be. It is his immortal part.” If nothing else, The Great American Railroad War reminds us of an inspired journalistic reaction to the crimes of an earlier age of robber barons, a welcome contrast to the bloviation that predominates in today’s all-talk news media. Perhaps it is time for citizens, intrigued by the ingenious initiative of Hearst, to fund first-rate writers and reporters to do the investigative work that is rapidly disappearing in a self-reflexive “news” media that is vaporizing itself and us in gas clouds of yak.

I sent the book’s author, Dennis Drabelle, a contributing editor and mysteries editor for The Washington Post Book World, some questions via e-mail about the relevance of the campaigns waged by Bierce and Norris. Here are his responses.

Arts Fuse: Why did you become interested in the campaign that Ambrose Bierce and Frank Norris waged against the Central Pacific railroad?

Dennis Drabelle: I’ve been a fan of Bierce ever since freshman year of high school, when we read his great story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” for English class, and the mystery of his disappearance at the end of his life only made him more interesting. On reading a biography of him, I noticed that he came to Washington to fight the railroad, and I thought this would make a good article for a local magazine. The article never materialized, but when I found out that Frank Norris had not only gone after the railroad in his own way—in his novel The Octopus—but had also reacquainted himself with Bierce’s anti-railroad articles before doing so, I saw the outlines of a book.

AF: Why should contemporary readers care about an attack on big business that took place over a hundred years ago?

Drabelle: I’m far from the first person to note that the current political climate is eerily reminiscent of the robber baron era. Many of us today are dismayed by the outsized influence of big money on politics and elections just as people were in the 1890s and the early years of the twentieth century.

AF: Is this a neglected episode in the history of American letters? If so, why?

Drabelle: Not entirely neglected. Every biography of Bierce—and there have been about half-a-dozen—mentions the episode, but none of them goes into much detail about it. What I’ve done is to flesh out what takes up a few paragraphs in those books into a blow-by-blow account of the campaign, which falls into several movements. It’s fun and instructive, I think, to watch a masterful stylist like Bierce take advantage of mistakes made by the railroad lobbyists while putting into service his great flair for irony and invective. The gossip columns and sardonic word-definitions he spent so much time writing out West are Bierce-Lite, but this is the real thing.

AF: A good portion of the book deals with Bierce, who was sent to Washington on behest of publisher William Randolph Hearst and his newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner. Bierce is a controversial figure in the history of American journalism—admired and reviled as a master of vituperation. Does this episode in his career help or hinder the reputation?

Drabelle: There are times in Bierce’s career when he seems to be simply excoriating his fellow human beings because he can. He himself said, late in his employment by Hearst, that he was tired of being “a chained bulldog.” But when he came to Washington in 1896, he had a foe worthy of him, and instead of merely hurling stylish insults, Bierce bore down, mastered the complexities of the legislative process, and delivered analysis laced with invective, rather than invective with a few pinches of analysis. (For example, one laughs at the dismissive label Bierce pinned on the Spanish-American war: “the Yanko Spanko War.” But one admires the protracted artfulness of his campaign against the CP.) So I think the episode adds a measure of seriousness and focus to his reputation.

AF: Why, after the success of Norris’s novel The Octopus, did so few American writers follow in his footsteps and write so directly—with reportorial verve—about the malfeasance of American corporations?

Drabelle: Probably because not enough people wanted to read such novels—for the most part, they are tendentious and dreary. Norris managed to avoid the great pitfall of writing political novels: creating wooden characters who act out fantasies by being either owner-ogres or pure battlers for improved conditions. Norris had the sense to talk to people who pointed out that not all Central Valley growers were spotless paragons, and he wangled an interview with Collis Huntington, the Central Pacific’s robber baron in chief, who impressed him with the complexity of the issues he was about to work into his fiction. Norris, in other words, found the negative capability by which a writer identifies with both sides of his story, whereas it has eluded so many other writers who wanted to follow in his footsteps.

Ambrose Bierce — his fusillade of irony and invective against the Central Pacific Railroad was the real thing.

AF: What resonance does the book’s conflict have between writers and a corporation have for us today? You suggest that Bierce and Norris acted at the wrong time to make a real difference in curtailing the growing influence of big business on government.

Drabelle: The resonance I see is how important it is to have an independent press—whether in the form of newspapers (printed or online) or books—to act as a countervailing force in our public life. I wouldn’t say that Bierce and Norris acted at the wrong time, exactly. Bierce had been taking potshots at the CP all along, and Norris probably couldn’t have written a book like The Octopus until he had passed through the Zola phase of his literary development. Yet it is true that the CP had its way in California throughout the 1870s and 1880s, souring voters on the form of government they had inherited and leading to the creation of the initiative, referendum, and recall—tools that, ironically, have been captured by big money themselves. If somehow the controversy that sent Bierce to Washington had occurred a decade sooner, perhaps the railroad would have been brought to heel by means of the normal legislative process, implemented by impartial regulatory bodies, and the state of California wouldn’t be in the mess it is in today.

AF: Investigative journalism is expensive and rare. In my CJR review of your book, I suggest that perhaps Hearst’s idea of sending Bierce with a team of professional journalists to the nation’s capital could be duplicated today. Why not start up Kickstarter campaigns aimed at sending teams and talented writers to Washington to uncover corruption?

Drabelle: Why not, indeed? Especially at a time when newspapers are cutting back on or closing their Washington bureaus altogether. Even if a newspaper does only what the Examiner did, send a “SWAT team” to Washington to report in detail on an issue of particular interest to the folks at home, that’s a good step. Multiply that several times to cover issues of importance to various regions, states, and cities, and you would have a lot of scrutiny of government, which of course is a healthy and necessary thing.

Tagged: Ambrose Bierce, Central Pacific Railroad, Dennis Drabelle, Frank Norris