Movie Review: Through the Eyes of Children

Two superb new films, Moonrise Kingdom and Beasts of the Southern Wild, revolve around children and the power of love.

Moonrise Kingdom and Beasts of the Southern Wild. At various New England cinemas.

By Tim Jackson.

Willa Cather believed that “a child’s attitude toward everything is an artist’s attitude.” In film, the unaffected presence of children revives buried emotions, ideas of identity, experiences of physical and moral courage, first love, and family bonds. We see the world with a fresh perspective, the baggage of propriety and socialization stripped away.

I recommend the French films Tomboy and Kid with a Bike and the Japanese film I Wish for remarkable performances by first-time, pre-teenage performers. Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom and Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, currently in theaters, are notable for both their gifted young actors and for how each sees the world through a child’s romantic imagination.

There is always something off-kilter about director Anderson’s view of the world, whether coping with the quirkiness of family as in The Royal Tenenbaums, the spiritual quest of three brothers in Darjeeling Limited, the absurdist Jacques Cousteau riff of The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, or animated forest animals with real world problems in The Fantastic Mr. Fox. I have learned to let go of traditional ideas about story and just give myself over to the world he has created.

But Moonrise Kingdom is something new for Anderson. It is dense with detail but wonderfully clear in its rambling storyline. It is told from a child’s vantage point, but this time children are the central characters in the plot as well. The narrative has plenty of forward motion despite its constellation of characters and side yarns.

On the surface, the film is about the struggle for love between two pre-teen pen pals, Sam Shakusky (Jared Gilman) and Suzy Bishop (Kara Hayward). Sam is a “Khaki Scout” at a camp run by Scout Master Ward (Edward Norton). He is an orphan while she lives with her parents, Walt (Bill Murray) and Laura (Frances McDormand), both attorneys. It is set on a small, mythical, New England island, more like Vinalhaven, Maine than Martha’s Vineyard but closer still to Never Never Land. Her parents oppose the relationship, so they run away together. We are clearly in the province of a children’s fable further enhanced by the colorful and imaginative hyper-reality of the film’s visual design. Every shot is chock full of little details. The camera is patient and shots are often static with action moving in and out of frame or panning laterally as details are revealed. It is tempting to compare it to Maurice Sendak or Chris Van Allsburg, but it is uniquely Wes Anderson.

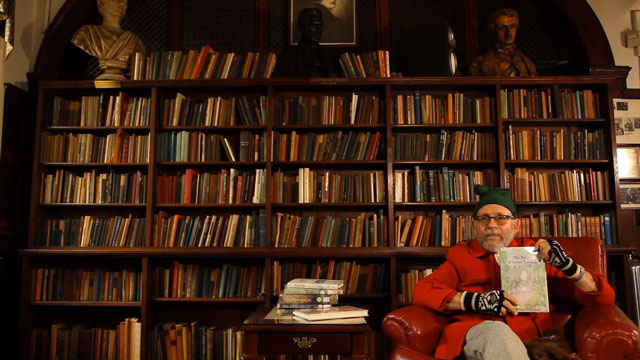

MOONRISE KINGDOM’s Library: Bob Balaban introduces animated sequences depicting fictional kids’ books, as read by young co-star Kara Hayward.

In one remarkable sequence, Sam and Suzy read letters to one another off-screen as we watch a series of scenarios so artfully composed they look like works of video art (the letters were actually composed by the young actors). Other sets look like children’s book dioramas. In the remarkable opening sequence, the camera prowls from room to room, peeking in on the action as we watch Suzy’s brothers listening to a Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 by Benjamin Britten. We hear the record’s child narrator say,

In order to show you how a big symphony orchestra is put together, Benjamin Britten has written a big piece of music that is made up of smaller pieces that show you all the parts of the orchestra. These smaller pieces are called variations, which means different ways of playing the same tune.

It strikes me that this is Anderson’s method. The “big piece of music” is love and faith and their triumph. His fantasy variations on the theme go from enchanting to way over the top. One of the more affecting scenes has Sam, in his underpants, standing with Suzy by the moonlit water in their makeshift camp, which they call Moonrise Kingdom, dancing, cooking, telling stories, and innocently learning to how to French kiss. At the other end of the emotional scale is a giant storm we know is coming because we have been directly introduced to the history of the island—called New Penzance—by an on-camera narrator (Bob Balaban in a red jacket and green beanie) who has warned that a big storm will be coming.

An earlier flashback foreshadowed the possibility of a miraculous and epic struggle: the previous summer the children had met at a performance of Noye’s Fludde (Noah’s Flood). Enchanted by Suzy’s performance as a raven at the play’s climax, the bespectacled, young Sam had marched backstage after the show and, ignoring everyone around, enthusiastically asked her what kind of bird she was portraying. She’s charmed by his boldness and an unlikely romance was born.

It took a lot of auditioning to find young actors as brave and intelligent as Kara Hayward (from Andover, MA) and Jared Gilman. Neither had acted before, except in school plays. They rehearsed for weeks and then jumped in. What they are able to show us is that the emotional and intellectual life of a child is as valid and deep as any adult. And this seems central to Anderson’s philosophy. These young actors convince us that the characters are both cunning and tender without resorting to being cute or cloying.

Gilman:

I had to take canoeing lessons and cooking over an open fire lessons. I had to learn how to flip a fish. I also had to do physical training. Wes had me watch Escape from Alcatraz because Clint Eastwood’s character in the film was similar to Sam, in the sense that they are both resourceful and capable.

Hayward:

You have to do what your character wants to do. Our characters wanted to kiss. You can’t argue with your character . . . I think young love is a thing adults can relate to. I think they will remember how it felt when they were young and love felt like it could take over their whole lives.

Anderson has outdone himself in casting and guiding his other actors, as well. These also include a muted and brilliant Bruce Willis as Captain Sharp, a nearly unrecognizable Harvey Keitel as Head Scout Commander Pierce, a deliciously officious Tilda Swinton as “Social Services,” and a brilliant cast of children. He has designed exquisite set pieces and miniatures and has scored exclusively with music from Benjamin Britten, Hank Williams, and French composer Alexandre Desplat. Anderson’s shooting is objective and formal, clean and precise.

The upshot is that he brings us back to a kind of Eden. It is the kids who bring life, passion, and power to this formal design as we drift into a surprisingly pure vision of innocence and longing for peace, love, and understanding.

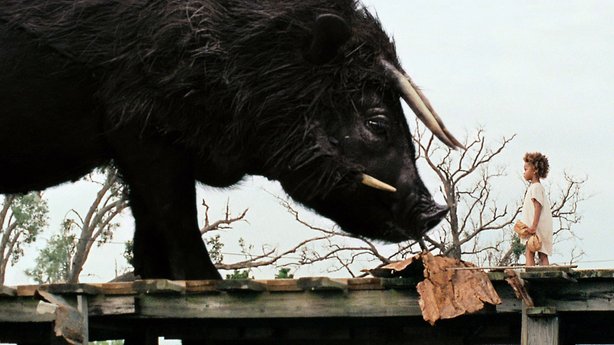

Where Moonrise Kingdom is a meticulously rendered poem of innocence and coming of age in mythical New England, Beasts of the Southern Wild is a sprawling, unstable, mytho-poetic story of Southern lives on the edge of survival. It is an amazing first feature for Benh Zeitlin who has created a world that is either completely mythological or exists somewhere in the dreams of a child whose world is so close to disaster that she imagines another reality. In this world, the ice caps are melting, and Beasts, released from the frozen ice, ravage the watery landscape.

This unstable tale is narrated by Hushpuppy, a six-year-old child played by Quvenzhané Wallis who obviously hasn’t had the time or experience to approach the role intellectually, but she fully inhabits the part. Her performance could win her an Academy Award—it’s that good. Hushpuppy narrates the film. The little actresses’ focus is so grounded, her face so earnest, that you believe in this surreal place. Even as you’re watching the film, it’s hard to know precisely where you are or what’s going on and where the story is headed.

Ostensibly, Hushpuppy is searching for her long-lost mother after her father falls ill. Her tough-love daddy, Wink (Dwight Henry), is preparing her for the day when he can no longer look after her. They live in a ramshackle, Southern town called the Bathtub, which is designed to feel like either post-Katrina New Orleans landscape or a post-apocalyptic landscape. The place is beset with natural and mythological disaster.

Ingenuity, community, and survivalism sustain the film’s scrappy group of characters. Despite the squalor and lack of civilization, this colorful community made up of black, white, and Cajun people, young and old, men and women, is full of music and laughter, and fed on luscious feasts of crayfish, crabs, seafood, and meat. Food as a communal ritual is central to the film: Wink teaches Hushpuppy how to feed herself and other people. It is of interest to note that Dwight Henry, who plays Wink, is a baker and chef who owns the Buttermilk Drop Bakery & Cafe. He turned the part down three times. It’s hard to believe he is a non-professional.

According to the Tulsa World, Henry said, “I knew the filmmakers because there’s a casting agency across the street from the bakery, and they used to come over in the mornings to get breakfast and doughnuts and things, and they put fliers in the bakery asking people to audition for an upcoming movie.” The producers eventually had to hunt him down.

“I wanted to take it, but I just refused to walk away from the business that I had worked so hard and so long to build,” Henry said. “But I thought about things, and they saw some things in me that I didn’t see in myself. They just had so much belief in me. I finally worked things out with my two partners, and I was able to leave and go do the movie, and everything since then has just been wonderful, wonderful.”

The screenplay is based on a stage play by Lucy Alibar called Juicy and Delicious, a bluegrass musical about sex and Southern food at the end of the world. Alibar explains,

Hushpuppy’s searching for the common denominator of all living beings. Every animal has a heart, every animal has parents, every animal has a bigger animal that wants to eat them . . . so much of eating animals today is a bigger conversation about industrialization, corporate ownership of food sources, etc. But Hushpuppy and her Dad live close to the land, grow their own food, and eat their own chickens. Hushpuppy’s examining how she’s part of the food chain when she’s eating animals. Like Miss Bathsheba says, “We’re all meat.”

The play, whose author is an old friend of Zeitlin, inspired the film, which very much reflects the imagination of the director. Sets were designed and decorated from found materials. These include a makeshift boat constructed of an old car and used tires and interiors constructed with the randomness of folk art and beauty of an Edward Kienholz installation. It looks like Mad Max and plays like a great folk tale. Take a look Zeitlin’s previous short film Glory at Sea to see the prototype for his design of the film.

Born and raised on Long Island, Zeitlin is the son of folklorists Steve Zeitlin and Amanda Dargan, which helps explain his unique sensibility. Before starting the film, he lived for some time in the South and became obsessed with its people and textures. He brings a knowing sense of folklore and vernacular culture to the film, eschewing predictability and cliché in search of an authentic Southern feel.

The acting and shooting feel uncertain and improvised. The plot seems to meander. Often it seems as if it’s being made up on the spot—until suddenly gargantuan, mythological Beasts make a startling appearance.

And then we have the amazing Quvenzhané Wallis. It’s hard to imagine how the film would work without her at the center. Her eyes challenge and hold the film steady. Her primal screech brings the world to attention. Her tears are real, they will break your heart and remind you of how deeply children feel, yet how tenaciously they grapple with the world. As Hushpupy says, “The entire universe depended on everything fitting together just right.” She makes sure that happens.

As with the children of Moonrise Kingdom, in the end it is all about the power of love.

Tagged: Beasts of the Southern Wild, Benh Zeitlin, Jared Gilman, Kara Hayward, Moonrise Kingdom, Quvenzhané Wallis

I’d rather see a flawed film by Wes Anderson (a fellow Texan) than a “perfect” film by anybody else.