Visual Arts Review: Ansel Adams — Water as Motion and Time

By using water as a lens to explore Ansel Adams’s artistry, this exhibition makes his fascination with motion and time crystal clear.

Ansel Adams: At Water’s Edge. At The Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA, through October 8.

By Yumi Araki

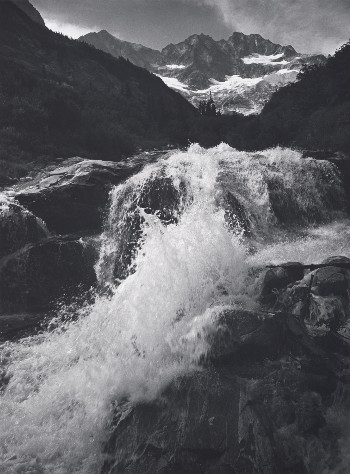

Waterfall, Northern Cascades, Washington, 1960 Photograph by Ansel Adams Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona; The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Mention Ansel Adams and monochrome landscapes of the vast American wild comes to mind.

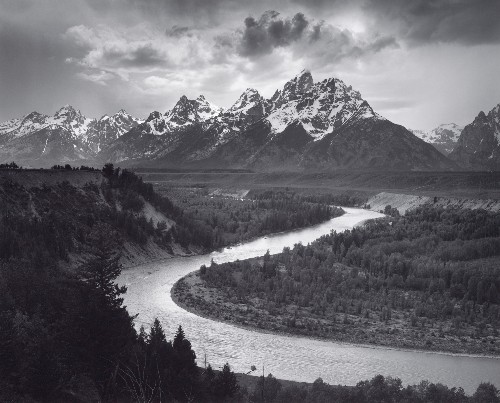

My first encounter with Adams’s work wasn’t until a few years ago, when I was browsing through a bookshop in search of a gift. There lay a subdued image of a black-and-white mountain range behind a winding river on the cover of a book simply titled Our National Parks. It could have been from any national park -— Yellowstone, Acadia, or even Glacier Bay -— there was nothing distinctive about the photograph or its presentation. Yet the book’s inside flap pronounced Adams as one of the most celebrated photographers in America, and I’d heard somewhere that his works are displayed in the Department of the Interior. What made him so revered? What is it about these landscapes that were so distinctively American?

The Peabody Essex Museum’s newest installation, Ansel Adams: At Water’s Edge, presents ample evidence of Adams’s majestic command of photography as an art form. His craft lies not necessarily in the subject matter of his photos, but in his technique and the experience it evokes so powerfully. The focus of the exhibition, water, strays from Adams’s signature mountains or arboreal habitats. Still, by using water as a lens to explore Adams’s artistry, the exhibition makes his fascination with motion and time crystal clear.

The exhibition is divided into the four junctures in Adams’s career: His early works, experiments capturing time and motion, establishing the F/64 School, and his later photography, which centers on the spectacular. Adams had been surrounded by water from his early childhood years in San Francisco, including his stint visiting Cape Cod when he was working for Polaroid in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Legend has it that Adams’s direction as an artist had been profoundly influenced by his childhood trip to Yosemite Park. But the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, where Adams broke his nose falling to the ground near the Golden Gate Bridge -— near the bay –arguably left a bigger, more visceral impression for an artist to mull over.

Taken when he was 14, one of Adams’s first photos depicts a snapshot of a gazebo-like structure along a river at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, where her father encouraged the budding photographer to engage in summer learning. The photo, a snapshot of San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts with its edges blurred and abstract composition, evokes a Renaissance painting landscape along the Arno or the Seine. Back then, photos weren’t considered art unless they indulged in a “picturesque” quality. Later, as if to rebel against this stricture, Adams begins cultivating a style that reverses the demand that photographs merely replicate what’s in front of the lens.

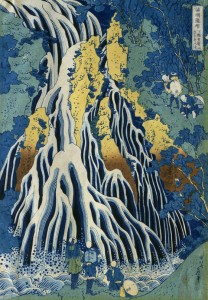

Some of the collection’s most dynamic pieces come from Adams’s compilation of waterfalls. Gushing over a peak of rocks in what otherwise looks like an unassuming creek, Fern Spring, Dusk, Yosemite Valley (cir. 1961), captures the silent roaring of falling water. The water’s blurred appearance captures movement over time and space with an energy that recalls Hokusai’s famous Cascade at Kirifuri Waterfall. Pieces such as Fern Spring underscore Adams’s contemplative inquiry into photography’s artistic potential.

In the 1920s and 30s, Adams formed a group with artists Willard Van Dyke and Edward Weston who share a common dissatisfaction for traditional interpretations of photography. The group’s name, “F/64,” was named for the highest aperture setting available on cameras during that era. The higher the aperture, the more vivid the subjects in the photos become. The clarity is articulated in works like Siesta Lake in Yosemite Park (1958), where the slit of bark nearest the lens, the dead tree in the background, and its reflection in the middle of the photo are caught via pristine resolution. This is what photo buffs call a deep depth of field, which isn’t the preferred camera setting because it doesn’t discriminate between what’s important and what isn’t in the picture. Our eyes naturally prefer shallow depths of fields: Those who are nearsighted will understand how our eyes — when focusing on thing — blurs out irrelevant peripheral stimuli.

But Adams and the F/64-ers defied this standard by producing photographs with hyper-real qualities. In Ocean, near Bolinas, the cliff, the ocean, and the edges appear to pop out from the canvas. His most famous photograph, The Grand Tetons and the Snake River, 1942 (one of the photographs from the Department of the Interior), features a spectacular view of a mountain, ominous clouds seeming to nestle at its top.

The Tetons and the Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1942

Photograph by Ansel Adams Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona; ©2011 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

It is this very ‘your are there’ sensation, the sense that one can almost feel or experience the scene of the photograph, that Adams explores in his later years. Spanning the entire height of the exhibition wall, two grandiose photographs of another unassuming, yet majestic national park landscape draw those who pass by with their magnanimity. Both of the portraits of national park forests draw viewers in with the almost life-size ratio of branches, mountain summits, and magnificent trees. On the wall, Alfred Stieglitz is alluded to as Adams’s inspiration for the collection, which he dubs “Equivalents.” Borrowing from Stieglitz’s proclamation, Adams came up with his own interpretation of ‘equivalency,’ suggesting that the photo should be an equivalent to the actual experience of beholding the scenery.

At the exit of the exhibition, a small guest book contained several pages of visitors’ feedback. As I flipped to the third page, a small sentence wedged between the last few lines and the page number struck me. Just as Adams was a man of brevity (“A good photograph is knowing where to stand”), this visitor’s comment captured the essence both of the exhibition and of Adams’s spirit: “Always appreciated Ansel Adams’s photography, but I didn’t know why until today.”

Brilliant bit of writing about this terrific photographers images. I can’t wait to view the exhibit which I would have missed if it wasn’t for this critique.

Thank you.