Classical Music Review: Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ Resurrected

By Caldwell Titcomb

Conductor Benjamin Zander celebrates the 30th anniversary of the Boston Philharmonic and his 70th birthday.

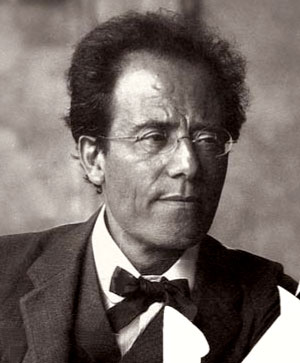

The two greatest post-Brahms symphonists – Gustav Mahler and Jean Sibelius – were markedly unalike. In 1907 their paths happened to cross in Helsinki, and they had several conversations. When the talk turned to the essence of symphony, Sibelius voiced his allegiance to “severity of style…and the inner connection between all the motives.” Mahler exclaimed, “No, symphony must be like the world – it must embrace everything!”

A clear example of Mahler’s attitude is his Symphony No. 2, called the “Resurrection Symphony,” which he had written between 1888 and 1894. Here he embraced not just life and death but the afterlife too. He used an oversize orchestra, including ten horns instead of four, six trumpets instead of three, two timpanists with six drums, two harps, and pipe organ, along with two vocal soloists and a large mixed chorus. The result is one of the most colossal achievements in all music.

Any live performance of the Mahler Second is a noteworthy cultural event. And this is what Symphony Hall housed on March 11. It celebrated a double occasion: the 30th anniversary of the Boston Philharmonic and the 70th birthday (two days earlier) of its founding conductor, Benjamin Zander. The British-born cellist-turned-conductor had led the Civic Symphony for several years, and was fired, ironically, for playing too much Mahler. The upshot was that all but one player left the Civic and in 1979 formed a new orchestra under Zander’s leadership. The Philharmonic had programmed the Mahler Second a couple of times in the 1980s, and it was a logical choice to resurrect it for this month’s double birthday.

A number of conductors have championed Mahler’s music over the decades – among them Bruno Walter, Willem Mengelberg, Eugene Ormandy, and Dimitri Mitropoulos. But it was Leonard Bernstein who was most responsible for elevating Mahler’s output into the standard repertory. Bernstein assimilated Mahler into his psyche and conductorial hands so completely that he sometimes felt that he himself had become Mahler. He first led Mahler in September of 1947, and the vehicle was this very “Resurrection Symphony.” Of the numerous live performances I have heard, the two at the top were both led by Bernstein: with the Residentie Orkest in Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw in July of 1950, and with the New York Philharmonic in Avery Fisher Hall in January of 1984. In Bernstein’s career he conducted nearly 400 Mahler performances.

Following Bernstein’s death in 1990, the Mahler mantle has to a considerable extent fallen on Zander’s shoulders. In the past decade Zander has been recording a Mahler symphony cycle with the London Philharmonia on the Telarc label. Appearing so far have been the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Ninth, with the “Resurrection” to be taped this month. (One hopes that the Deryck Cooke performing version of the masterly not-quite-finished Tenth will eventually be included – a project that Bernstein regrettably avoided, even though not a single bar is missing from the composer’s autograph.)

The Boston Philharmonic’s performance was not flawless, but it was pretty impressive all the same. The roster of 116 players included a majority of professionals plus a contingent of advanced students. Once past the not entirely precise rushing scales at the outset, the strings played with admirable ensemble throughout the ninety-minute work, and the treacherous brass parts suffered only one horn slip near the end of the first movement. Zander obviously knew the piece cold, and his choice of tempi was consistently convincing (Mahler put hundreds of directions into his score).

Mahler originally entitled the first movement “Todtenfeier” (“Funeral Rites”). Why begin with death? Mahler stated that this is the funeral of the “hero” of the First Symphony. It is in the key of C-minor, not coincidentally that of the funeral march in Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony. (As Zander commented in his pre-concert talk, “Mahler knew a lot about death.” Both his parents died during this piece’s composition. Of Mahler’s 13 siblings, nine died young, and one of his own daughters would die at the age of four.) This movement is a marvelous example of sonata-form, rich in thematic material (including the opening motive of the famous medieval “Dies irae” tune invoked by many composers.) At the crucial structural spot where the development section leads back to the recapitulation, Mahler wrote two highly dissonant iterated chords that are hair-raising, buttressed by a high-G kettledrum struck repeatedly with a wooden mallet. Zander captured this moment magnificently. And in the coda the soft trombones were lovely.

Although some consider it silly, Mahler made a point of printing in the score that “here follows a pause of at least five minutes.” To allow the intended contemplation, Zander sat down in a chair for the specified amount of time. After that, the two vocal soloists came on stage and took their seats, and Zander resumed his place on the podium.

The second movement – a nostalgic look at a pleasant life – is a ländler, an Austrian folkdance in slow triple meter (Mahler cautioned, “Never rush.”) The composer called it “Schubertian.” The usual ternary form is extended to five sections, with the main theme appearing three times – the second time with a gorgeous countermelody in the cellos, and the last time with plucked strings and delightful woodwind interpolations.

Next comes a scherzo with running sixteenth-notes suggestive of the moto perpetuo tradition. Mahler drew his thematic material from his “Knaben Wunderhorn” song about St. Anthony preaching to the fishes ineffectively. Mahler spoke of “the never-to-be-understood hustle and bustle of life [that] may seem dreadful….senseless.” There are two trios, each stated twice, so the entire scheme presents nine sections instead of the usual three. Mahler briefly sticks in a parodic quotation from the scherzo of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony.

Without a break, the fourth movement presents another “Wunderhorn” setting, this one titled “Urlicht” (“Primeval Light”), and sung by the alto soloist, with an emphasis on woodwind and brass. Mahler stated that the poem reflects “the questioning and agonized searching of the soul for God.” Mahler marks the first section “very solemn but simple,” the middle “somewhat livelier,” and the third “slow, as at the start.” Susan Platts, a British-born Canadian, has sung this piece many times, so she didn’t need a score in hand. She sang expressively, but her diction could have been a bit clearer.

Mahler was stymied for a long time about how to conclude this symphony. But when he attended the 1894 funeral of conductor Hans von Bülow , he heard the choir singing Friedrich Klopstock’s hymn “Auferstehung” (“Resurrection”), and this proved to be his “Aha!” moment. He went on to produce a huge 35-minute finale, culminating in a slightly altered Klopstock text plus further verses by Mahler himself. This is a complex and intricately organized movement, handled with utter mastery. From time to time, offstage fanfares require brass players to exit and return to their places. There is birdsong, and the “Dies irae” beautifully played as a soft chorale and later loudly as a march of dead souls when the earth trembles and graves open (the percussion crescendos here were terrifying), and the souls ascend to God’s light (in the key of E-flat, the relative major of the work’s basic C-minor tonality).

Zander made one mistake: he had his 138-person chorus (drawn from the New England Conservatory Chorus and the Tufts University Chorale) stand much too soon. The audience thus was cued that we were about to hear the chorus. Mahler wanted the chorus to remain seated when it started to sing. He marked the music pianississimo and “misterioso,” and intended that this music should sneak in almost imperceptibly. The chorus should stand only on reaching “With wings that I have won in ardent love’s endeavor I shall soar to light.” In a marvelous inspiration, the solo soprano (Ilana Davidson here) doubles the choral sopranos and then (twice) splits away and floats into the firmament. Eventually all the singers are full-throated, joined by the recently renovated Symphony Hall pipe organ at full blast and the ringing of bells – Resurrection has been achieved.

In his audience pep-talk Zander asserted, “No one hearing the end for the first time will ever forget it.” It also packs a wallop even for those who know it well. Zander and his charges deservedly came forth again and again for bows (a special salute goes to flutist Kathy Boyd, oboist Peggy Pearson, trombonists Greg Spiridopoulos, Robert Couture, Johnny Watkins and Wang Wei, and timpanists Ed Meltzer and Aziz Bernard). At the last bow, Zander simply picked up Mahler’s score and raised it high in the air. Our world is currently in a parlous state, but the Mahler Second can make it seem a little bit better. Bless you, Gustav.

Tagged: Benjamin-Zander, Boston-Philharmonic, Caldwell-Titcomb, Featured, Gustav-Mahler, Jean-sibelius, Music

Excellent review, of course.