Theater Review: Boxed In — “Yesterday Happened: Remembering H. M.”

Dramatist and director Wesley Savick faces a number of fascinating but formidable theatrical challenges, and the generally compelling “Yesterday Happened” (how could it not be, given its story?) takes an honorable, visually striking swipe at the problems.

Yesterday Happened: Remembering H. M. Written and Directed by Wesley Savick. Staged by Catalyst Collaborative@MIT at the Central Square Theater, Cambridge, MA, through May 13.

By Bill Marx

The Brain—is wider than the sky—

For—put them side by side—

The one the other will contain

With Ease—and You—beside—

The Brain is deeper than the sea—

For—hold them—Blue to Blue—

The one the other will absorb—

As Sponges—Buckets—do—

The Brain is just the weight of God—

For—Heft them—Pound for Pound—

And they will differ—if they do—

As Syllable from Sound—

— Emily Dickinson, “The Brain -— is wider than the sky.”

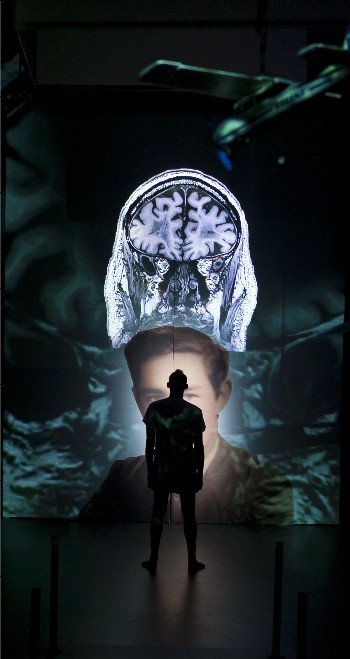

Man Meets Brain: Barlow Adamson as Henry Molaison in YESTERDAY HAPPENED: REMEMBERING H.M. Photo: A.R. Sinclair Photography.

Yesterday Happened: Remembering H. M. touches on, but doesn’t explore deeply enough, a terrifying vision of imaginative vertigo. What happens when the expanse of the “Brain” (by which Dickinson means the mind) shrinks from the infinity of the sky to the head of a pin? The idea fascinates, doubly so because it is based on a real-life case of enormous scientific importance for the study of memory and the brain. But how, on stage rather in the pages of a novel, do you evoke such a monstrously thin trickle of a stream of consciousness? The task calls for a minimalist poet, but even Samuel Beckett allowed his characters flickers of memory, if only as a means to torment them. The predicament dramatized in Yesterday Happened threatens to render the horror of the absurd, absurd.

Receiving its world premiere at the Central Square Theater, the play (a brusque 90 minutes with no intermission) is based on the predicament of Henry Molaison, who in 1953, as the unintended result of brain surgery aimed to relieve his severe epilepsy, was left with “anterograde amnesia.” According to the program notes, “he could not form any new declarative memories after the surgery.” In general, everything was a perpetual wonder to the poor guy—he could learn new skills through repetition, but he had no memory of how he attained them. A large portion of his hippocampus removed, Henry was a boon to scientists, who for decades examined the man, learning from his plight that there were different kinds of memory, and then mapping where they were generated in the brain.

But what about Henry’s consciousness of his plight? No doubt picturing the skewed perspective of this intelligent man would tax the syntax of Gertrude Stein. The fact that he couldn’t maintain new memories made him of value to millions, but he was trapped in a hellishly circumscribed world in which his recall of a childhood airplane trip was all that remained of the past. Based on the play (which draws on testimony of people who knew Henry, who died at the age of 82 in 2008), he was a mild-mannered man who never changed. He had come to a separate peace with his predicament, apparently content to solve crossword puzzles for hours, respond to repetitive scientific requests to work out questions and mazes, and tell himself that he was living for the good of others.

Dramatist and director Wesley Savick faces a number of fascinating but formidable theatrical challenges, and the generally compelling Yesterday Happened (how could it not be, given its story?) takes an honorable, visually striking swipe at the problems. But he hasn’t really surmounted an elemental obstacle — there is no conflict in this drama. We first meet Henry as he sits in a chair in a white cube at center stage, scientists wheeling him about as they pepper the guy with questions. Henry is in a box, and the metaphor extends to playwright Savick as well. He doesn’t just want to repeat, through the dialogue of the doctors and nurses, the information in the program notes (though there is some of that). Instead, he wants to evoke Henry’s state of mind, often through the impressions he makes on others. Savick introduces a series of short episodes, from a sympathetic nurse who reacts to her patient’s predicament with anguished empathy to Henry breaking into song, a recreation of his memory of an airplane trip (‘wider than the sky’), and a weird visit from the surgeon who is going to remove Henry’s brain after he dies.

Thought it all, Henry is calm and collected, a figure of wry inscrutability, looking at a flock of geese with smiling incredulity, shaking his head at the same headlines at each reading of the daily newspaper. As Henry, Barlow Adamson gives a disciplined and captivating performance –- the actor uses his comic skills, a sort of existential deadpan, to create a chillingly genial image of unflappability, including intimations that his character knows a touch more than he tells, that there is a mystery in his head worth figuring out. And that is what Yesterday Happened as a theater piece depends on – pushing audiences into taking their imaginations into unthinkable realms.

Debra Wise and Barlow Adamson in YESTERDAY HAPPENED: REMEMBERING H.M. Photo: A.R. Sinclair Photography.

But here is where Savick flinches. In the program notes, he writes about how Henry’s “evident and opaque” condition evokes envy and terror. But the play, afflicted with the Awakenings syndrome (a favorite of weak-minded critics), is more interested in generating inspiration than tragedy, saluting Henry as a martyr who isn’t suffering all that greatly given his benefit to science and mankind. Poked and prodded, questioned and examined by shrinks and doctors, Henry has no one to articulate the pain of his existence –- we hear that Henry lived at home until his fifties, yet there are no voices of relatives or family in the play to provide a non-scientific emotional perspective. We and Henry are generally left at the tender mercies of his professional caretakers, with no more than tentative hints that there are limitations to their well-meaning ministrations. Working with MIT scientists doesn’t mean putting science beyond criticism.

For me, the most tantalizing scene in Yesterday Happened revolves around what might or might not be a nightmare of Henry’s. At night he is woken up repeatedly and questioned by doctors about his dreams. At one point (it is reported to us), the confused Henry snaps at his interlocutors and tells them to shut up, suggesting that he could become angry, and, because he was conscious of his helpless state, could feel depression. But that is an exceptional moment of anguish, a rare glimpse into a frightening psychological dissolve, in a show that goes out of its way to make Henry’s unquestionable use to the world –- his involuntary heroism –- the reassuring payoff for his treadmill of an existence.

Adamson is aided and abetted by an ensemble of doctors (mostly), played with interchangeable dispatch by Debra Wise, Anna Kohler, and Steven Barkhimer. More distinctive is the production’s brilliant visual design, particularly the miraculous final image of brain, man, and mortality, and the playful music of Tod Machover, played with agility by Tae Kim. The sound and visuals of Yesterday Happened allude to perilous depths that the script never reaches.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Catalyst Collaborative@MIT, Central Square Theater, Debra Wise, Henry Molaison, Wesley Savick