Music/Poetry Review: “Letters to Distant Cities” — An Appetite for the Forlorn

The strength of the poetry is the ambiance it creates. Narrative is almost totally submerged in imagery, which may seem natural enough in verse but often is not the case.

Letters to Distant Cities by Shara Worden. New Amsterdam.

By Vincent Czyz

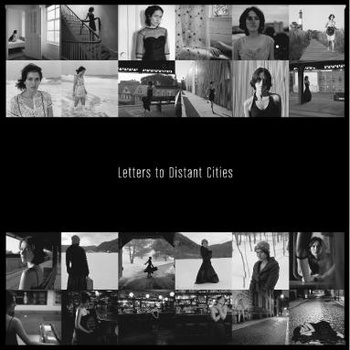

Letters to Distant Cities comes in a handsome, black box with a matte finish. The box appears to be bound by a band of glossy black—an illusion created by the differing textures of the materials. Here, on this strip of polished black, the title is rendered in small, silver letters. Everything about this mixed-media collection bespeaks high production values and attention to detail. The box includes a CD consisting of two songs, 24 recited poems, and almost as many accompanying instrumentals. There are also 24 black-and-white photographs printed on thick cardstock; each has a poem or a poem fragment printed on the back. The photos themselves, by Murat Eyüboğlu, capture a woman on a cobbled street at night, the same woman waiting for a train at day’s end and in an empty bar—among other settings and situations.

My Brightest Diamond opens the CD with a haunting composition called “The Sea,” which is more a mood conjured in sound than a song. Shara Worden, the lead singer for the band, has the sort of dreamily pensive voice the subtleties of the music call for. “Invisible,” performed by Clare and the Reason, closes out the CD. Slightly less moody than “The Sea” and somewhat more upbeat, “Invisible” is also on somewhat less intimate terms with the ethereal. Bookended by these two songs are the poems, which, written by Mustafa Ziyalan, a native of Turkey, are recited by Worden. Weaving in and out between the poems are Rob Moose’s instrumental interludes. I loved these brief, interstitial cadences, which seemed to consist mainly of a subdued violin and another stringed instrument—beyond my limited musical capabilities to identify—being plucked. The poems take up the bulk of the CD, however, and it’s clear the songs and music are ancillary.

The strength of the poetry is the ambiance it creates. Narrative is almost totally submerged in imagery, which may seem natural enough in verse but often is not the case. The poems tend to work below the surface—as music does—and go straight to the sunless caverns the self rarely wanders while awake. Ziyalan practices a species of mild surrealism (“A drop from the full moon/which would burst/if you would touch it with something/other your tongue”), but he’s given it his own stamp. At times playful and whimsical, more often the poetry is a kind of keening, instilling a vague sense of loss—a romantic rather than a surrealistic preoccupation.

It’s not mine, this deep red shadow,

It’s not me this cloud I disown,

I glide with the weightlessness of the dispossessed

To the bottom I can’t find for the life of me.

I cross the spot where I’m seen long ago

Honing the cloud likeness further . . .

There is plenty to admire among Ziyalan’s poems, including this beautifully wrought image:

Life will stop when she leaves

And remain like a skull

Forgotten in the desert night.

And this single striking line:

In what earth is loneliness planted?

If the poems dwell on the forlorn, they do so with resignation and acceptance or simply with brevity and a certain narrative distance. There is nothing whiny or sentimental.

The sea floated up the rivers

into the sky.

Something she thought eternal,

something like childhood,

was gone.

The penchant for the forlorn is perhaps part of a Turkish sensibility. I was reminded of Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk and his book Istanbul: Memories and the City (reviewed here on The Arts Fuse). At one point, he writes, “Offering no clarity, veiling reality instead, hüzün brings us comfort, softening the view like the condensation on a window when a teakettle has been spouting steam on a summer’s day.” Hüzün, Pamuk, says, is a sort of communal rather than private melancholy. Indeed, I think what Pamuk describes may be as much an element of the poetic as it is a psychological state. In “Prose, Thinly Disguised as an IKEA Superstore,” I tried to express this connection.

Dusk and dawn are generally considered be the most poetic times of day. Time seems to be in a holding pattern, to have stilled itself long enough for a grainy photo or a hazy recollection. Solidity is flattened and hollowed out into silhouette, and because we are in two worlds at once, because clarity has been sacrificed, we are striding away from prose. Similarly, fog can turn even the most prosaic building into something worth looking at for the same reason: edges blurred, form is now unreliable.

The artists who contributed to Letters to Distant Cities have worked in unison in pursuit of what seems to me a similar vision: the black-and-white photographs, the black packaging of the collection, the restrained instrumentals by Moose, the opening song—on the edge of mourning—and Ziyalan’s images and words lead to a sort of gray place, a landscape of shadows, and while the poetry does not turn away from the unpleasant, it cushions the blow with a kind of acceptance, with an eye still searching for what might be redeeming even when someone is “shot through the wings.”

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City.

Tagged: Letters to Distant Cities, Mustafa Ziyalan, Poetry