Visual Arts: Where were you in May 1968?

By Gary Schwartz

This question was asked by a Dutch newspaper last spring. At the time I did not get around to answering it. What they were after were experiences related to the students and workers revolt in France and other revolutionary manifestations of the Spirit of 68. My first reaction was that I was not involved. I was excited by the events and hoped that a bloodless revolution would put an end to the nouveau ancien régime in Gaullist Europe, but I did not take the train to Paris or build a barricade.

Quite to the contrary, I was engaged in the most bourgeois kinds of behavior imaginable. On 26 April 1968 I got married in Brooklyn to the wife by whom I fathered a child born on 26 January 1969 (count the months) and with whom I celebrated our fortieth wedding anniversary on 26 April 2008 in the house that we had signed for earlier in April 1968. On 1 June 1968 I began work as a Dutch civil servant at the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD). The RKD called me a wetenschappelijke medewerker, a scholarly associate, but the civil service recognized no such title, so that I was given the rank of hoofdcommies, chief clerk, which made much more of an impression on the Rabobank-Boerenleenbank Maarssen when in September we took out a mortgage that has financed much of our life since.

Loekie and I drove south on a honeymoon trip, stopping first in New Castle, Delaware, a romantic relic of colonial America. We spent part of our wedding-gift stash on four amazingly inexpensive old quilts, giving us a powerful acquisitive thrill of a kind we have experienced all too often since. On our next stop we did get a massive dose of 1968. I wanted to show Loekie Baltimore, where I lived from 1961 to 1965 as a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University. We arrived there less than a month after the murder of Martin Luther King. My old house on Greenmount and 30th was a few blocks north of the line of devastation inflicted a few weeks earlier by the Baltimore blacks mainly on themselves. We visited the sweet woman who lived above my rented floors and who had cleaned for me. Mary Jones was the Cherokee-Irish daughter of a worker from the long-gone neighboring steel yards. She had a saintly simplicity that I treasured as long as I could avoid discussion of race relations. She was illiterate, so I conducted her correspondence for her from 1962 to 1965. Most of it was about her welfare benefits and an alcoholic son who was in and out of prison and would beat her when he was home.

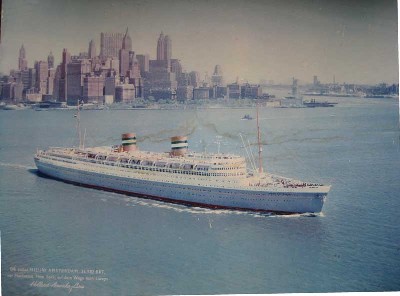

Back in New York we bundled Loekie’s five-year-old daughter Anne and our wedding gifts onto the S.S. Rotterdam (no weight or size limit imposed by the Holland-America Line, no duty charged by Dutch customs on wedding gifts). [An aside: Of all the revolutions that may be said to have taken place since 1968, one that continues to puzzle me is this: in 1971 the Rotterdam was taken off the transatlantic passenger route for which it was built, and in the course of the 70s all the other dozens of passenger vessels that plied the Atlantic followed suit. Few experiences in my life have been as enjoyable as my Atlantic crossings on the S.S. Zion in 1958, the S.S. France in 1965 and the S.S. Rotterdam in 1968. No cruise can match that combination of sybaritism and purposefulness. Why should mankind have sacrificed something so exceptional so completely just because an uncomfortable, ungracious alternative was cheaper and faster? This reminds me of some of the choices between competing technologies that were decided in favor of inferior choices. End aside.]

On board we met a Dutchman who was returning home with a message from America that he was sure would revolutionize his native country. He nearly succeeded. Jan Foudraine is a psychiatrist who was seized with the conviction that psychiatry had a destructive effect on people and on society. In 1971 he came out with a book that challenged the basis of medical psychiatry, Wie is van hout? (Not made of wood: a psychiatrist discovers his own profession). In less than a year it went through fourteen printings, as wave after wave of well-meaning Dutchmen opened up to the realization that classical psychiatry and its institutions had dubious and downright nasty sides. Fortunately or unfortunately for the world, Foudraine’s return from exile did not have the lasting impact of Lenin’s to Russia or Ayatollah Khomeini’s to Iran. When after several years of fame he became a follower of Bhagwan Sri Rajneesh, he lost the authority that his M.D. conveyed. If psychiatric care in the Netherlands was improved as a result of Foudraine’s challenge I cannot judge. He certainly did not bring about a reduction in the use of pills and shots. Worse, on the radio I hear about death after death of patients in “seclusion,” even that the treatment of psychiatric patients in the Netherlands might lead to a warning from Human Rights Watch.

In my own life the radical changes took place not in the 1960s but the 1950s. The political heroes of my childhood, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman, made way for characters like Joe McCarthy, Richard Nixon and the nuclear brinksman who signed my first passport, John Foster Dulles. Today, on Election Day 2008, I recall my first bitter disappointment with the American electorate, when Adlai Stevenson was defeated in 1952.

In the 1950s I lost religion and traded in the parochial Jewish world in which I was raised for the international Republic of Letters I still inhabit. A year in Israel cured me (almost) of Zionism. Not even my move in 1965 from the east coast of the U.S. to the west coast of Europe brought about that great a shift in the values by which I try to live.

My conversions of the 1950s were moreover acts of revolt. Nearly all my schoolmates remained shulgoing patriots. In 1968, when the conformist thing to do was to put a flower in your hair and join a commune, I got married and sailed off on the Rotterdam with my bride and her little girl. It was a great year.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor and publisher; teacher, lecturer and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book (2006). His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, has been appearing every other week since September 1996. His most recent book on Rembrandt is one of the six titles nominated for the Banister Fletcher Award for the most deserving book on art or architecture of the past year. Contact him at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl