Film Commentary: “The Artist” — Rooting for Simplicity

“The Artist” works on two levels: the audience in the film and the audience watching the film are entertained by the same things. And it’s that simplicity –- the era when silent movies were all they had and it was good enough –- is the real protagonist.

By Justin Marble

Whether it’s Federico Fellini’s attempt at a self-portrait or an ode to the joy of film like Cinema Paradiso, it’s highly doubtful that directors will ever tire of tackling their favorite subject: movies. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the egocentric nature of Hollywood and its directors or maybe it’s simply people focusing on what they love – probably a combination of both – but there’s been no shortage of movies about movies throughout history. Often adored by film critics for obvious reasons, these movies can often suffer from redundancy simply because of the unchanging nature of Hollywood. Is there anything that Robert Altman said in The Player that wouldn’t still hold true today? Probably not, but plenty of films and television series have belabored the point nonetheless.

Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist is, surprisingly, a breath of fresh air as far as “movies about movies” go. As the film plays out, it’s easy to point out all of the pitfalls that lesser movies would have fallen into –- becoming too engrossed with nostalgia, taking cheap shots at studio executives, repeating what other, better films have already said or simply painting itself into a corner of irrelevance. And yet, just like the way Charlie Chaplin could waltz through chaos and emerge unscathed, The Artist ends with nary a flaw to be found. It’s cheerful without being cloying, adeptly executes tonal shifts without losing the audience and evokes nostalgia for a bygone era while offering plenty of food for thought on the modern age. Even Hollywood itself can’t avoid the film’s charm, as the film appears to be a shoe-in for Best Picture.

Were the film set in any other era, this might not be the case. In fact, The Artist may actually be set in the last era that Hollywood actually underwent a significant change. Jumping from silent to sound is the technological leap that HD and 3-D wish they were. There’s also simply a general attitude shift that accompanies this change. This was the era where it seemed almost anyone could become a movie star with a little luck and elbow grease. The Player was brought up above as an example that Hollywood hasn’t changed much in the past few years, but you’ll notice plenty of modern-day characteristics in 1950’s Sunset Boulevard as well. The Artist, on the other hand, looks at a truly different era that is likely foreign to today’s audiences.

That would make Jean Dujardin’s George Valentin the Norma Desmond character, although the similarities end at the fact that they are both aging silent film stars. Berenice Bejo, meanwhile, plays the role of the Peppy Miller, who walks off the street and into stardom. Valentin starts the film on top, but as sound begins to become more popular, he’s cast aside in favor of Miller, whom he actually helped land her first job. The constant, as in any film about Hollywood, is the studio, embodied by John Goodman’s Al Zimmer.

Again, this is where lesser films could have fallen. With Valentin essentially cast aside by Zimmer, the audience has an easy bad guy to root against. It would be entirely too safe to simply bash the fat cats on top and turn the film into “Occupy 1920s Hollywood.” Yet the movie has a sense of history, and the silent film stars did not suddenly convince everyone to go back to reading intertitles again. Valentin sinks into a downward spiral that he simply cannot get out of on his own, even with Miller and a loyal chauffer (James Cromwell) looking out for him.

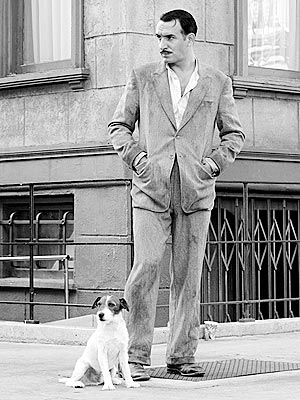

The genius of the film is that the audience does not root for any one character. They root for simplicity. Valentin is likeable enough, but he’s also arrogant and brusque. In fact, his pet dog is probably the more sympathetic character. Miller ends up on top shortly after the film begins, so there’s no real conflict for her to overcome. Even Zimmer, the ready-built bad guy, has that affable John Goodman nature that makes him tough to hate, and Hazanavicius does nothing to make him villainous.

So what makes the film compelling? From the opening sequence, where we see Valentin entertain a crowd of people with his dog and a few tricks, the film shows where its heart lies. It works on two levels: the audience in the film and the audience watching the film are entertained by the same things. And it’s that simplicity –- the era when silent movies were all they had and it was good enough – is the real protagonist. As the noise starts to build and people start talking, that urge sets in –- can’t they just go back to the silent movies? There’s something innocent and pure and safe about them.

And this is how Hazanavicius weaves nostalgia and relevance together. All these years later, are there movies that stand the test of time better than the films of Charlie Chaplin? Divorced from the era they were made, outclassed in every way by new technology, there’s still something truly timeless about the Little Tramp and his adventures. The Artist is a love letter to this simplicity of cinema, and it makes its case by being entirely simple itself. Loving this film recalls the memories of every film like it that you ever loved.

But a film that basically says “they don’t make ‘em like they used to, huh?” isn’t special or unique. It’s been done before, and no matter how much it may ring true it’s not enough to save a film on it’s own. It’s not until you start thinking about that Phantom Menace 3-D poster in the lobby that it hits how relevant this is to today’s Hollywood. Suddenly, a film like the original Star Wars, which was light years ahead of anything Chaplin could have dreamed of, is the low-tech relic. It doesn’t have CGI or digital picture and it’s in plain-old 2-D. Heck, they actually had to make models of the spaceships and hold them up against a black backdrop. They might as well have had a title card pop up that said “Luke, I am your father.”

I’m no Luddite and there’s certainly something to be said for the fact that 99 percent of the films I enjoy have sound. And I’m sure the next big technological leap will be so revolutionary that it’ll be a mandate for all films to be up to that standard. Still, it’s nice to catch that breath of fresh air once and again, when a film like The Artist comes along and reminds us that the simple stuff still works, and sometimes silence is golden.

I’m going to see this today and am looking forward to it.