World Books Review: Strange Articulations of Being Human

(I am one of the judges for the Best Translated Book Award (fiction division) sponsored by Three Percent. The five finalists will be announced in New York on February 16th. Three Percent honcho Chad Post needed help to meet his goal of posting a commentary on each of the 25 volumes on the BTB’s fiction long list. I have written this on The Ninth, one of my favorite novels in translation last year. I will post a piece about Brecht at Night—by the late Estonian novelist and theater artist Mati Unt—on Friday.)

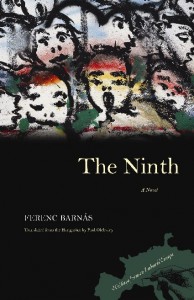

The Ninth by Ferenc Barnás, translated from the Hungarian by Paul Olchváry, Northwestern University Press (Writings from an Unbound Europe), 159 pages, $16.95

Reviewed By Bill Marx

A brilliantly unconventional look at life in a small village outside of Budapest in the late 1960s, Ferenc Barnás’s marvelous novel The Ninth comes off as an inventively dour, sardonically humorous version of Huckleberry Finn, except that the book’s nine-year-old narrator can’t light out for the territories once he begins to understand the duplicities of home, society, and morality. His indigence is too overwhelming, his family situation too absurd (he has nine siblings), and the soft authoritarianism of the government too robustly restrictive.

What’s more, Barnás gives his observant child hero an additional handicap—a disability that makes it difficult for him to speak and to read. Thus, the book’s central metaphor works itself out with grim logic: in surroundings this resolutely repressive, everything of value—creativity, morality, truth, and humanity—is bottled up inside, pressurized. What sort of steam could escape the Communist stopper? The answer suggests why Barnás’s third novel, which he admits is autobiographical, takes the form it does—a child’s frank, fanciful, and anarchistic view of moral survival amid repression.

Yet Barnás doesn’t revel in the gloom, an admirable artistry of refusal that turns away from predictable opportunities for extremism to nurture an indirection and subtlety that only deepens the factual surrealism of the situation and the time. The ninth child lives in a poverty-stricken, secretive, Catholic family that scrapes along by selling rosaries and religious gewgaws condemned by the Communist government. The boy’s domestic and school life is marked by starvation, overcrowding (the ten children sleep in three beds), overwork, and abuse. His father is tyrannical and short-tempered; his mother is kind but passive. In the course of the book, the family’s exhausting focus, under the father’s stern command, is to earn enough money to move into a larger house.

Barnás conveys the environment’s barbarism through ironic humor (“One afternoon, when for some reason I wasn’t in the mood to mutilate frogs out in the yard with the others . . .”) and memories of violence that are kept offstage (“the other day our father gave us twenty lashes on our soles for being late, he used the iron’s chord but it was better than watching klaro get it . . .”). Catholicism serves as a rich satiric source of meager solace, wry hypocrisy, and amusingly secular observations, such as the peculiar but understandable satisfactions the inarticulate kid finds in serving as an altar boy: “It’s so good to see people shut their eyes while sticking their tongues above the tray! Nowhere else could I see so many different sorts of tongues; lots of them are quivering, and some are colored stranger than I ever would have thought.”

Ferenc Barnás

It is this agile emphasis on homey detail rather than trauma and despair that has led the book’s too few reviewers to dwell on Barnás’s admirable modesty and nuance. For me, The Ninth is all the more provocative because it depicts, through a nimble exploration of a child’s stream-of-consciousness, the vicissitudes of his imagination and the tee-tottering state of his soul amid the village’s sickening perfidy, corruption, and stupidity. When the kid steals money from his teacher and spends his ill-gotten gains on cakes and candies for his classmates, the idea is not to stage a pint-sized crime and punishment.

Barnás wants us to watch his narrator shape the parameters of the self he will become, dramatizing whether the child will absorb the guilt and spiritual poverty around him or become an individual by embracing the possibility of change, by speaking the self-incriminating truth. Memorably, his confession seems to burst out of him, against his will: “Everything becomes even hotter inside me as something begins surging up into my chest, something sure to gush into my mouth in no time: the saliva is already sour in my throat, as at other times. ‘It was me,’ I say.” What looks like a modest tale of growing up becomes a far more ambitious examination of the formation of an ethical consciousness, almost out of thin air, in an authoritarian state built on lies and coercion.

Barnás’s nine-year-old narrator is a brave construct, an unconsciously sophisticated consciousness that filters life’s hardships and decisions through a startling innocence, an amoral earnestness. The character’s emotional life is weirdly attenuated, his thoughts often taking on a gnomic vagueness redolent of post-modern philosophy: “It must count a lot, what we assume on account of what, and what we imagine we hear in what; at least that’s what the last month taught me.” Translator Paul Olchváry skillfully captures the novel’s fascinating blend of arch artificiality, sharp-eyed realism, and antic fantasy, all at the service of depicting the inner life of the marginal among us.