Theater Review: “The Boys of Winter”

By Bill Marx

“The Boys of Winter”

Written by Barry Brodsky, Eric Small and Dean B. Kaner. Directed by Bridget Kathleen O’Leary. Presented by BKS Productions at Boston Playwrights Theatre, Boston, MA, through September 21.

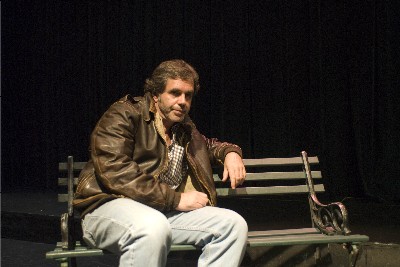

John Greiner-Ferris as the disgruntled vet in “The Boys of Winter”

In his superb new essay collection “Writing in the Dark,” Israeli writer David Grossman discloses what he sees as the secret of literature: it “can repeatedly redeem for us the tragedy of the one from the statistics of the millions. The one for whom the story is written and the one who reads the story.” The challenge for the artist — whether novelist or playwright — is to anchor his redemptive view of tragedy in the individual rather than in the general, to focus on the rich contradictions of the specific rather than on the rote unanimity of the stereotypical.

Based on the true story of a trio of Midwestern teens ground up in the Vietnam War, “The Boys of Winter” has the virtue of focusing on a national tragedy, its waste and senselessness a precursor for the current debacle in Iraq as well as foreshadowing the challenges for veterans returning home from Iraq and Afghanistan. Aside from an honorable exception or two, Boston theaters have chosen not to tackle Iraq, preferring to stick to various forms of escapism, from the primitive to the sophisticated. BKS Productions has the satisfaction of bucking the political head-in-the-sand trend.

Also, the staging, efficiently directed by Bridget Kathleen O’Leary, is modestly affecting, aside from some from over ripe emoting from lead actor John Greiner-Ferris, who plays a number of key roles. But this antiwar script spends far too much time spelling out its anti-Establishment leanings and cranking out rote conflicts to dare venture beyond the circumscribed dramatic category of “lesson to be learned.” Coming home from war must be a particular kind of hell, an exile filled with its own devilish psychological nooks and crannies, but “The Boys of Winter” serves up a predictable political fable of innocence lost, focusing more on the dragooning of confused teens into the army than exploring how war transforms its warriors. The result is that no one in the audience will be surprised or shaken up by the well-intentioned proceedings.

Michael Jorgensen and John Oxenford in “The Boys of Winter”

Thankfully, unlike last season’s overwrought “Streamers,” which also dealt with the Vietnam War, “The Boys of Winter,” doesn’t wallow in ersatz Greek tragedy. The model here appears to be TV doc-u-drama — the program notes say that script is adapted from a screenplay. In the present, a bitter and angry Vietnam veteran flashes back to 1966. He and his two best friends, ace hockey high school players from the lower middle class, find themselves forsaking dreams of sport and college to head off for Vietnam, marching off to war because of economic desperation, childhood loyalty, and self-destructive patriotism.

The play focuses on the most talented and conflicted of the three guys, Doug. He wants to earn a hockey scholarship for college and deferment, a decision encouraged by the kid’s mother and girl friend, which are trying to keep him out of the conflict. But Doug’s friendship with his buddies and the gung-ho attitude of his father push him into signing up, which lead to predictably tragic consequences.

Playwrights Brodsky, Small, and Kaner are more concerned with pumping up schematic pressures on Doug than making his parents, coach, or girl friend into individuals. They are cookie-cutter devices designed to shape Doug one way or the other, to or away from the war. The proponent of Vietnam as a maker-of-men, Doug’s blustering father, offers little of the necessary galvanic resistance needed to complicate or undercut the play’s pieties. A stray scene here or there suggests an attempt to go beyond broad-brush dramatics, such a delightfully out-of-nowhere discussion of whether the film “Grand Illusion” is an antiwar play or an awkwardly revelatory hockey game between father and son.

By the end, “The Boys of Winter” dissolves into a heuristic exercise. The veteran patiently explains to the audience his nasty case of survivor guilt before, much like Marlow in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” deciding in good old humanist fashion that those on the home front must be protected from the pain of war. We just can’t stand the truth. But antiwar theater must be the place where redemption, if it is to come, follows a long and hard look at icy realities – “The Boys of Winter” is not coldhearted enough to go there.

Mr. Marx:

Many thanks for coming to the play and obviously giving it a good deal of thought before writing your review.

The only thing I would like to comment on is your description of the “grand illusion” scene as “delightfully out-of-nowhere.” Perhaps we didn’t get it right, but our intention with that scene was that it would foreshadow Merle’s PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) problem, which would be paid off in the “awkwardly revelatory” hockey scene between father and son later in the play.

In 1966, world war II vets were in their 40s and 50s, and PTSD wasn’t very commonly diagnosed or discussed as it is with today’s vietnam and iraq/afghanistan veterans. Merle’s boorish patriotism, at least in part, was a cover for his own insecurities which were a result of his reactions to the horrors of war he saw in his own youth.

At any rate, I really do appreciate your comments, and thanks again for attending.

barry brodsky