Theater Commentary: An Anything-But-Banal Love Story

The play does not address Hannah Arendt’s rationalizations or the reasons for her dedication to Martin Heidegger, though the dramatist’s title hints that it is the banal truth of the irrationality of love.

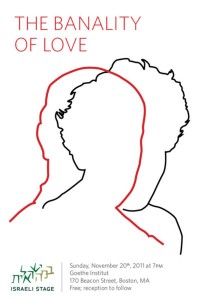

The Banality of Love by Savyon Liebrecht. Staged reading directed by Guy Ben-Aharon. Presented by Israeli Stage. At the Bill Bordy Theatre, Emerson College, Boston, MA, November 17; At the Goethe Institut, Boston MA, November 20.

By Ian Thal

This past November, Israeli Stage, a Boston-based theater company dedicated to the presentation of Israeli plays in translation, put on two staged readings of Savyon Liebrecht’s The Banality of Love. The play explores one of the major affairs of 20th-century letters: the romance between Martin Heidegger, arguably the most important philosopher of the last century, and his student, the famed political theorist Hannah Arendt.

The affair has long been a topic of controversy and not simply for the mundane reason that it was between a German teacher and his Jewish student between the two World Wars (Heidegger had also previously been involved with his half-Jewish student, Elisabeth Blockman). The philosopher was married: he and his wife are now known to have had something of an open marriage, with the younger of their two sons fathered by Friedel Caesar. The interest arises from the fact that Arendt became celebrated for her 1951 critique The Origins of Totalitarianism, while Heidegger had, by 1933, when he assumed the Rectorship of Freiburg University, become a public supporter of Nazism and remained unrepentant regarding his politics until his death in 1976.

Though Liebrecht’s play is framed by a 1975 meeting between Arendt and a fictitious, Israeli interviewer, much of the drama chronicles the tempestuous affair between the two thinkers from its start in 1924, moving from their increasing estrangement as Heidegger becomes more entranced with Hitler to a dénouement as the former lovers re-establish a cautious friendship after the war. The 1975 interview establishes parallel themes: Arendt’s ambivalence towards her past relationship as well as her mixed feelings regarding the Zionist project, Israel ‘s right to try Adolf Eichmann, and the actions of many Jewish leaders during the Holocaust.

The interview also deals with Israeli ambivalence towards German Jews like Arendt (Yekkes) who continue to espouse German culture, as well as many Jewish intellectuals’ frustrations about Arendt. Meanwhile, the story within the story explores Heidegger’s contradictions: his fascination with Judaism and his Jewish students alongside his willingness to support an explicitly anti-Semitic regime.

All of these are fascinating themes, but the play never focuses on the central question posed by the relationship between Arendt and Heidegger: why, when so many of Heidegger’s most brilliant and influential students were Jewish, was Arendt the only one to espouse Heidegger’s political rehabilitation?

While many of her classmates accepted evidence of Heidegger’s Nazism as central to his thought, Arendt used her 1971 commemorative essay “Martin Heidegger at Eighty” to portray Heidegger as apolitical, seeing his involvement with Nazism as an example of a naïvité to which intellectuals are prone. More than an uncomfortable case of loyalty is at stake here: because David Farrell Krell decided to exclude Heidegger’s 1933 rectorial address (“The Self-Assertion of the German University”) from his anthology Basic Writings, Arendt’s apologia greatly influenced how Heidegger’s politics were perceived by a generation of American philosophy students. (By contrast one should consider that Robert C. Tucker’s popular Marx-Engels Reader includes the essay “On The Jewish Question.”)

In more recent years, it has become clear that the political theorist’s public statements regarding her teacher’s politics were wrong and that her classmates were right. While Heidegger’s 1927 masterwork, Being and Time, is not a political work, proto-fascist themes are easily found, most notably in the emphasis the book places on authenticity. Once aware of the inevitability of death, the authentic individual chooses a life that is grounded in tradition and national, even regional identity. Essentially, Heidegger suggests that authentically means embracing one’s primal roots and rejecting the superficiality of modernism. Likewise, Heidegger’s personal politics had long been nationalistic, militaristic, and anti-democratic: he had merely drifted from the Catholic German nationalism of his years as a seminarian to the secular German nationalism of his adulthood.

Dramatist Savyon Liebrecht— too few playwrights attempt to seriously engage at all the lives and works of the major thinkers.

By the time of his 1933 rectorial address (which is quoted in Liebrecht’s play), Heidegger had not merely endorsed NSDAP and such changes to the university as the militarization of the student body and the elimination of academic freedom but interpreted these new policies as an expression of the German people’s authenticity. Whether or not Heidegger could or cared to infer the genocidal nature of the new regime, there was something about the party that resonated with his thought. He never admitted that he had been in error.

Liebrecht does not address Arendt’s rationalizations or the reasons for her dedication to Heidegger, though the dramatist’s title suggests that it is the banal truth of the irrationality of love. This neglects both Arendt the theorist and Arendt the public intellectual. Is her portrait of an innocently banal Heidegger merely the flip side of her portrait of Adolf Eichmann as a ghostly bureaucrat?

Historians have shown that neither portrait jibes with the evidence: Just as Heidegger embraced his own personal brand of Nazism, Eichmann was an idealistic anti-Semite and architect of genocide. Neither of these men were mere functionaries of a faceless bureaucracy Arendt famously describes as a government of “everyone and no one” in 1958’s The Human Condition—a concept that neatly maps Heidegger’s own conception of “inauthenticity” onto modern governance.

Essentially, Liebrecht’s Arendt is not the public intellectual who engaged in the political controversies of her day. Arendt’s own account of the “Final Solution to the Jewish question” was greatly indebted to her having read the manuscript of Raul Hilberg’s seminal, historical account The Destruction of the European Jews, a book whose publication she attempted to suppress. (Hilberg, who had closely studied the decision making behind the genocide, was a critic of Arendt’s “banality of evil” hypothesis.)

Furthermore, her indebtedness to Heidegger’s philosophy led to the anti-modernist elements of her own influential brand of heterodox, anti-Stalinist Marxism. Indeed, the romantic anti-modernism that had once been the province of the far-right now, by way of Heidegger’s influence, now influences the anti-scientific, anti-technological discourse on the left as well. The latter rearing its head in the work of that most Heideggerian of “radical” theater artists: Peter Schumann of Bread & Puppet Theatre.

Liebrecht’s failure to plumb the depths of Arendt’s thinking about the ideology her former lover espoused may be based in her desire to use the Heidegger-Arendt relationship more as an allegory for the relationship between Israel and Germany or, more generally, Israel and Europe. Israel adopted European-style parliamentary politics and a welfare state. Germany, most infamously, along much of Europe, spent much of the last century in the grips of authoritarianism and totalitarianism. Thus European perspectives towards Israel often seem more grounded in the range of ambivalent to hostile attitudes that it has historically had towards its Jewish population than the ideals espoused by the now democratic regimes of the EU.

This attempt to make the drama of Heidegger and Arendt into an allegory for something other than their own intellectual legacy is compounded by another of Liebrecht’s choices. The younger Arendt is paired with a fictitious classmate and confidante named Rafael Mendelsohn, a Jewish student who has little trouble recognizing Heidegger’s sympathies toward Nazism. Emanuel Levinas, Karl Löwith, and Hans Jonas (who, like Arendt, was on the faculty of the New School for Social Research) each made distinct contributions to their field; however, as a composite character, Mendelsohn is indistinct, providing little but Jewish disapproval of sleeping with the enemy.

Still, too few playwrights attempt to seriously engage at all the lives and works of the major thinkers, and Liebrecht does a fine job of explaining some of the more revolutionary aspects of Heidegger’s “fundamental ontology,” addressing the significance of mortality in his philosophy as well as how his phenomenology of tool use effectively dissolves the subject/object dichotomy that had dominated modern academic philosophy (and still does, in some departments.)

Critics are generally reluctant to comment to publish comments on readings due to the fact that blocking is elementary and the actors are still on-book. However, in the Israeli Stage’s reading, Craig Mathers was particularly striking as the young Heidegger of the 1920s and ‘30s. As mentioned in an interview on Israeli Stage’s own website, the actor has been an enthusiastic reader of Heidegger as an undergrad and was able to evoke the act of philosophizing with a convincing degree of verisimilitude. So The Banality of Love has its virtues, but we are still waiting for the definitive play about the anything-but-banal relationship between Heidegger and Arendt.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: Hannah Arendt, Ian Thal, Martin Heidegger, Savyon Liebrecht

I came upon this essay today by Sol Stern, that while neither addressing Arendt’s relationship with Heidegger in detail, nor Liebrecht’s play specifically, it does show how Arendt had a rather long streak of issuing philosophical proclamations that had little basis in empirical fact (like her teacher) often with great rhetorical power.