Theater Review: Not Enough Political Heat in “The Kitchen”

National Theatre director Bijan Sheibani chose artistry of movement, beautiful as it is, over the battering belittlement of really hard, unappreciated work, the facts of sweat and stupor.

The Kitchen by Arnold Wesker. Presented by The National Theatre in HD. Check on the NTLive site to check for remaining screenings in New England.

By Joann Green Breuer

At the age of 79, the political playwright Arnold Wesker is having a lively, if somewhat off-point, revival of his 1959 documentary-ish play, The Kitchen. The circular stage of London’s National Theatre is transformed into the eponymous kitchen of a bustling, large, offstage restaurant. The reality of oven flames and steamy pot is clearly meant also as metaphor by their juxtaposition with mimed manipulations of absent actual food.

More than working class travail is the message here. Theatricality triumphs politics. The production opens in darkness, save for islands of gas jet flames, the stage lights slowly rising on thousands of flasks, bowls, ladles, and bins. The question is where are we? Trapped in a circle of Dante’s hell, dabbling through Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory, or dancing in the chamber of Mickey Mouse’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice? A bit of each, as it happens.

Wesker comes by his acquaintance with this culinary venue honestly. His mother was a cook. Among the many menial jobs he worked at as young man, before entering the London School of Film Technique (now the London Film School), Wesker worked in restaurant kitchens. He ended his cooking career high in the gustatory echelon as a pastry chef. His theatre career did not, by his own estimation, rise so smoothly as his cakes. After productions in off West End theaters of his well-regarded and broadly noted trilogy, Chicken Soup With Barley, Roots, and I’m Talking about Jerusalem, Wesker’s reputation and productions entered, as Wesker terms it, his “unfashionable period.”

Trevor Nunn, during his tenure as Artistic Director, broke a contract to stage The Journalists at the Royal Shakespeare Company, resulting in Wesker’s futile lawsuit. The coup de professional grace for Wesker was the fate of his play Shylock, which imagines The Merchant of Venice from the point of view of the Jewish money-lender. Zero Mostel, cast as Shylock for a Broadway production, died after dress rehearsal.

Wesker, now living with political passions and Parkinson’s disease, despite the National’s current, expensive nod to this work and despite his knighthood in 2006, still harbors resentments about “the arrogance of” critics, producers, and artistic directors, whom he deems insufficiently appreciative of him, whether through the dearth of artistic acumen, anti-Semitism, or both.

So, does where does The Kitchen weigh in?

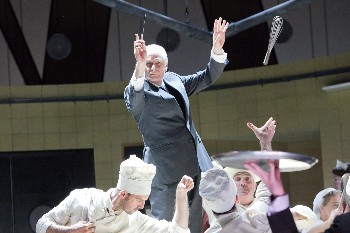

The choregraphed wait staff in the National Theatre’s production of THE KITCHEN. Photo: Marc Brenner.

In this elaborately choreographed conception, act one bears most of the responsibility for the mismatch of, admittedly skilled, physical movement and textual meaning in what Wesker intended to be a socially revelatory piece. British-Iranian stage director Bijan Sheibani collaborated with movement director Aline David to create a ballet-like swarm in this beehive of a workspace. Early rehearsals were spent with renowned restaurateur Jeremy Lee training the cast on the the correct way to slice onions and fillet a fish. It’s all in the wrist, by the way.

Keeping the 31 actors from bumping into each other, except on purpose, is David’s job, which she does masterfully, as white clad cooks step, turn, lean, reach, and weave from prep to pan, as waitresses in red dress and white waist apron walk-rush around them, picking up orders in a kind of round dance, quick and clean, bearing the same alienation from realism as the invisible food does to the specter of pale steam.

The whooshing sizzle of steam morphs to melodic waltz; sporadic silences and freezes punctuate the graceful staging. Dialogue is terse and exposition heavy; a love triangle about to fracture (Tom Brooke and Rosie Thompson), a calmly abusive proprietor (Bruce Myers!), a dangerously brass butcher (Ian Burfield), an Irish newbie (Rory Keenan), and the idealized pastry chef—shades of autobiography—(Samuel Roukin). It is an obviously mixed multicultural stew, with the German Brooke as the love-obsessed hero at the center of the thin plot, and long patches of spoken German as well, perhaps odd because England had only recently emerged from an immensely destructive victory in war with that nation.

All actors are true to their predictable character. Unfortunately, none seem to display much more. Yes, they are, as workers, dehumanized, but the aim of theater, eventually, is to humanize those robots. Given the sparse dialogue and long periods of dialogue-free theater time, I put the blame, in act one, for this almost sterile class consciousness on Sheibani. He chose artistry of movement, beautiful as it is, over the battering belittlement of really hard, unappreciated work, the facts of sweat and stupor.

The second act takes place that evening in the now quiet kitchen. The day’s toil is ended, exhaustion gives way to speech and dream, violence, and Myers’ s cold regard of all his hired human machines. Yet, what might have been political rage is overcome by that doomed love triangle, personal, yes, and perhaps conventional sublimation but feeling a bit petty in the face of the enormity of cast, set, and the social issues raised.

A contemporary production of The Kitchen is warranted. Naturalism is irrelevant and probably impossible, not only because of this complex environment but because film does that genre so well. As for the subject of restaurants, Anthony Bourdain and Gordon Ramsay have divulged their rough, house kitchen secrets to covert most of us all home to strictly vegan even while McDonald’s and its ilk have altered our palate to high levels of fat and salt. Ironically, more and more TV channels are devoted to exotic foods and the celebrity chefs who devise them.

The truth is, food today is a leisure priority that it was not when Wesker conceived The Kitchen. Any revival of essential value demands another priority: Wesker’s emphasis on the economic and social issues raised by serving food. The political vision in this still unfulfilled text is how respect and honor are lost in a job of drudgery, albeit skilled. Sheibani’s production respects and even honors the skill, but, I regret to say, insufficiently evokes the humanity.