Movie Review: Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975 — Scattered, Skewed, But Engaging

By Harvey Blume

The Swedes, to be sure, came for first-hand footage about the Black Power movement. How they managed to forget about that footage for decades is a story only they can tell. But you feel, in frame after frame, that Black Power was superimposed over what really made America problematic for them and much of the world: Vietnam.

The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975. Directed Göran Olsson. This intriguing documentary, made up of first-hand footage about the Black Power movement, will air on WGBH’s Independent Lens this Thursday (Feb 9) @ 10 p.m.

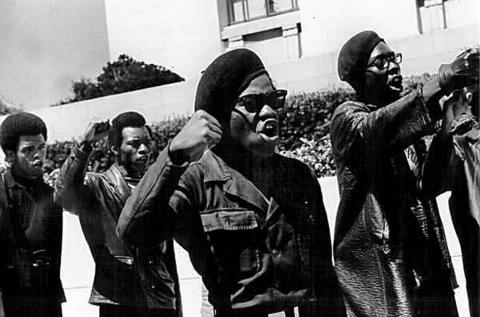

The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975\ includes footage of Stokely Carmichael in Stockholm in 1967. Photo: Lars Hjelm

When a friend of mine joined the Occupy Boston protest in Dewey Square recently, he introduced himself to a young woman camped out there by saying, “you know, I went to lots of protests in the ’60s.” She replied—with fine anti-boomer scorn—”yeah, and what good did you do?”

It’s true his protests, and mine, did not usher in a world free from the need for further protest—we’re as far from utopia now as then—but I would say to her in his defense, and mine, that we did, over quite a strenuous 10-year period, help stop a war, a major war, one that involved tens of thousands of Americans dying and an order of magnitude more Vietnamese, and, excuse me—hey, nice bandanna you got there, cool tent—but what exactly have you accomplished to date in Dewey Square?

I mention this not merely to come to the defense of a fellow boomer—boomer though I am, I sympathize with, encourage, anti-boomer sentiment among oncoming, impatient generations—but because the war in Vietnam we did our bit to stop is the backdrop, if not the context, for The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975.

The documentary footage for this film was moldering in the basement of Swedish journalists who visited the United States in 1967 to see what this country was really about. Their first stop, for some reason, was Florida—not a high class resort, but a small town whose beach was in the process of being bulldozed to pieces. After a brief chat with a luncheonette owner in that community who works a seven day week but thinks the United States is the greatest country on earth—”Hey, you can tell the President to shove it if you want”—the Swedes push on to an inner, darker, ghetto Florida, which is where they attach to the Black Power movement.

Their portrayal of that movement has some lovely moments. I don’t remember Stokely Carmichael being so soft-spoken, so calm, logical, and sweet. I remember ruinous rage or, more precisely, its effects—more ruinous, in the end, to inner city blacks who set fire to their own communities than to any whites in any “white power structure,” as the expression went. But when the Swedes film Stokely saying “Burn Baby Burn,” it’s in a living room. His friends laugh softly as Stokely chants a proto-rap song he had composed, in which he gently, quite reverently, puts Dr. Martin Luther King behind him while setting fire to bits of paper in an ashtray. Burn baby burn.

Neither in that scene nor any other does Stokely seem predisposed to violence. Neither is he in the least willing to point away from the traumatic effects of racism on the country or on his own family. (The most noted scene in the film is the one in which Stokely takes the microphone from Swedish interlocutors and lovingly prods his mother to explain why they were more poor than they had to be, why his father was always first to be laid off). At one point, again, very gently, he says he, and many blacks of his generation, were simply not as merciful or patient as Dr. Martin Luther King in opposing racism.

Superimposed on this footage are commentaries by African Americans—some too young to have known it first hand—on the Black Power movement. One such commentary is by a contemporary rap artist who says that though his songs sell precisely because they dwell on drug culture and thug violence, when police snatched him off a plane in 2010 it had nothing to do with those lyrics: it was because their digital snooping indicated he had been listening to a pivotal Black Power speech by Stokely in 1967.

Can it be? Do the ’60s, the Black Power ’60s, haunt United States homeland security operations to that twisted degree? If only the filmmakers pursued the question further. But The Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975 does not pursue things further. It is inconclusive, scattered, even skewed, but rarely less than engaging.

There is much of Angela Davis in this film, some Bobby Seale, snippets of Huey Newton and Malcolm X. You see the Black Panthers at their best—responding to hunger and lack of education in the black community by feeding and teaching children—but when it comes to the Panther’s gun toting bravado (their provocative readiness to “Off the Pig!), you get the feeling the Swedes opted to edit that footage out.

You hear Louis Farrakhan putting forth the Nation of Islam’s view that white people are the botched results of an experiment by the superior, original, black race. He, too, is compelled to say something profound about pigs, chortling weirdly as he maintains that human beings must at all cost avoid consuming the filthy flesh of the swine.

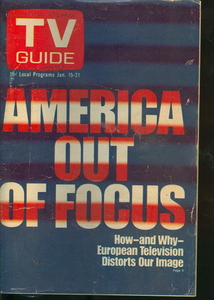

One pivotal bit for me was an interchange between the Swedes and the editor of TV Guide. This editor, after a trip to Europe, dedicated an issue of TV Guide to refuting the negative conclusion that, it seemed to him, European and, worst of all, Swedish television had arrived at about the United States. All they showed, he complains, is America at its worst—Jim Crow, riots, the storming of Attica, B52s carpet-bombing Vietnam. He admits America has problems, but what about its good side?

The Swedish journalists don’t ever speak up about their motives, but I suspect he was right about why they had come: they were fixated on the wrong side of America—Jim Crow, the terrible string of assassinations (JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcolm), B52s—as were, it should be said, many Americans and not only black Americans. The wrong side of America could suck you down.

The Swedes, to be sure, came for first-hand footage about the Black Power movement. How they managed to forget about that footage for decades is a story only they can tell. But you feel, in frame after frame, that Black Power was superimposed over what really made America problematic for them and much of the world: Vietnam. The film closes on black GIs returning from Vietnam addicted to heroin. It maintains, further, that agencies of the American government flooded the black community with heroin, then cocaine. Addiction would snuff out politics. Drugs would trump Black Power.

Did American authorities actually green light drug flow into Harlem? The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 doesn’t work to establish that charge. But it doesn’t have to do much to establish that violence gushed in from Vietnam. Violence flowed freely, contaminating, distorting, everything, not least of all the anti-war movement—violence of repression, violence of response. Violence was in, and Vietnam an inexhaustible source. Violence was the drug that most helped to destroy and foment the self-destruction of Black Power.

So, to return to Dewey Square, it must be admitted that the protesters of my generation left much of the wrong side of America intact. We have often been accused of insufficient staying power, of quitting too early. Perhaps so. But we did, quite a lot of us, put in at least a solid decade of our lives and played some role in ending the war in Vietnam. I permit myself to wonder if the tent dwellers of Dewey Square will put in anything like that amount of time to clarifying, sticking with, and winning any of their demands.

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse, and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: Black Panthers, Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, Occupy Boston, STokely Carmichael, Short Fuse

Harvey, the tragedy of the boomers (& our continuing inability to effect positive change) comes from our ongoing denial about our earliest political legacy. Far from helping “stop” the war in Vietnam the demonstrations of the late 60’s and early 70’s kept the war going a good five years after the policy makers in the military and foreign policy establishments had concluded that the war couldn’t be won and were seeking viable exit strategies. Worse, the yippie demonstrations during the Democratic National Convention (not to mention the burning cities brought to us by the black power movement) ushered in a a 40 year Republican counter-revolution that radically redefined the American center to the right.

I was arrested at the counter-inaugural of ’69 when we marched behind Vietcong flags shouting Ho-Ho-Ho Chi Min, the NLF is going to win. I was only 12 so I don’t fault my political immaturity to much. But if Nixon had been writing our script we couldn’t have served his interests better. Indeed many of our leaders were quite explicit about the strategy–it has to get worse before it gets better. And not a few have since been revealed as FBI snitches and agent provocateurs, including the Rev. Al Sharpton. Back in the day, any black kid with an attitude who got arrested for ANYTHING got three choices. Go to jail, go to Vietnam or work for the “mod squad” and get paid to do what you wanted to do anyway, stick it to the man. The movement was riddled with them.

The time to have quit was when we were ahead, after we powered Gene McCarthy & forced LBJ to not seek another term, when all the Democratic candidates (including the hapless Hubert Humphrey) were committed to a speedy end to the war. Our demonstrations succeeded in getting the country to question the morality, necessity & viability of the war. At that point we should have focused on the political process to answer the question with finality. It wouldn’t have been so much fun but it would have saved millions of lives in Vietnam & Cambodia. And we’d have national health care by now, among other things.

Instead we got drunk on our momentary media celebrity and illusory power. The whole world was watching, it was all about us & our narcissistic personalities felt fulfilled. For a moment of glorious instant gratification we handed the country to the right for the better part of 40 years. The damning question isn’t “what good did we do?”. It’s “how much harm did we cause?”. It’s not surprising that so few who partook of this moment can ask that hard question. Our most cherished legacy, that we ended the war in Vietnam, is our most dubious.

May the occupants learn the true lessons from our past, lest they be condemned to repeat them!

i agree it’s necessary to learn from the past in order not to repeat it, but to do so it’s first of all necessary to distinguish fact from fantasy.

sorry, but the yippie demos during the chicago dnc of 1968 did not generate what all observers — bystanders, journalists, pols — characterized as a police riot, courtesy of mayor daley’s finest.

as for “hapless hubert humphrey” planning to end the war in vietnam, perhaps you are privy to some secret transmission from him; in public he gave no one any reason to believe that so far as vietnam was concerned he was anything but johnson’s lackey. in other words, the war would continue, the draft would continue. as you say, you were too young to face the immediate consequences. but for those compelled to face them, a life of endless protest was perhaps a little less “fun” than you seem to imagine.

as for lbj himself, it was a genuine tragedy that he sacrificed the great society he was indeed making strides toward building in order to pursue and escalate an unspeakable war. perhaps you would like to blame that on boomers, too. i think it had more to do with johnson’s hubris, and america’s difficulty in coming to terms with its first major imperial defeat.

i do agree with you that the anti-war movement was prey to excesses, rhetorical and physical, that fueled the years of reaction to come. i tried, in my review of “the black power mixtape 1967-1975” to point, for example, to the romance with violence to which many of us, black and white, were susceptible. (i wrote that review in part to warn today’s protesters away from the allure of violent confrontation).

but you completely fail to understand just how much violence was zeitgeist in the late ’60s/early ’70s. the assassinations — jfk, rfk, mlk and macolm — not only deprived this country of the high caliber political leadership it so badly needed, but challenged belief in any such thing as due “political process”. then of course there was the war itself, more than a decade of transparent lies and increasingly manifest atrocities. the war in vietnam was pushing this country toward civil war.

boomers did not create that situation, though too often we lost our way in it. as for ending the war in vietnam, no, boomers did not accomplish that. the vietnamese were most responsible. protests, initiated among boomers before spreading through middle america, helped.