Visual Arts Review: Emotion, Time, and Eros in the work of Damon Lehrer and Rick Berry

Comparing Rick Berry’s expressionist paintings with Damon Lehrer’s exquisitely rendered, classical, and contemplative work made me wonder about the expressionist style in general. By this I mean that artistic terrain where the passions, vehemence, or ferocity of the artist so colors the work as to form a powerful but distorting lens through which we see the work.

It Figures. At the William Scott Gallery, 450 Harrison Avenue, #65, Boston, MA. Until September 30.

This show brilliantly contrasts two artists, Damon Lehrer and Rick Berry, and the wildly different ways they approach figurative painting. This will be a short review; I will look at a few of my favorite pieces and the questions that arise from them.

(For the questions that the artists have for each other see Damon Lehrer’s interview of Rick Berry.)

Expressionism

Rick Berry’s No Metal Men is violent and restless, fierce with strokes of palette knife or finger or brush. One arm seems amputated within the frame, the head, other arm, and legs are sliced by the edge of the picture. This is very much in keeping with the other works of Berry’s in the show: even when his style is calmer and more representational, he almost never gives us an intact face. Parts are missing, stripped, or smudged, as though the subject has been physically wounded or psychologically maimed. No Metal Men with its puzzling title and masterful hints of transparent glass or plastic, over wood (or is it bronze?) with teal shadows, may indicate a statue or some non-terrestrial, human figure. It is one of the strongest and most pleasing of his works here.

Comparing this work of Berry’s with Lehrer’s exquisitely rendered, classical, and contemplative work made me wonder about the expressionist style in general. By this I mean that artistic terrain where the passions, vehemence, or ferocity of the artist so colors the work as to form a powerful but distorting lens through which we see the work: the terrain where the figure seems built out of shards rather than strokes.

Of course, all artists present their work through some lens or other, colored by their philosophy, their skill, their mood at the moment, and their intention—but in the classical tradition (perhaps because we have been so immersed in it), it seems as though we do not see the distortions and can disregard those lenses. The painter paints; the viewer regards and thinks—seemingly free to go in any direction with those thoughts.

With expressionism, however, the artist so strongly imposes a view that we are hemmed in and our thoughts and reactions are corralled along certain much narrower, predetermined avenues, often along the lines of: the world is violent, cruel, rough, frightening, mutilating—albeit not without a certain spooky beauty.

This can work very well if the emotional energy of the artist strikes something within us. Then we go along happily caroming off the narrow walls of the expressionist intent, gathering more energy as we go. Swept thus, we forget to rebel against or be offended by the closeness of the atmosphere, the breathlessness of the thought compartment where little is left for us to do. For the artist, with his shards and blades, has done a lot of the imaginative response work for us. At times, of course, this is not by choice. This is simply the way this particular piece has to be. Art arises from the passions, as well as from the intellect, and is by nature informed and colored by its genesis.

When it doesn’t work, though, when the energy and vehemence just seems like so much hacking and flailing, then it can leave us flat or even annoyed. We wonder why the artist doesn’t trust us to invent our own responses and feels that all the emotion must be spelled out by the surface execution of the work.

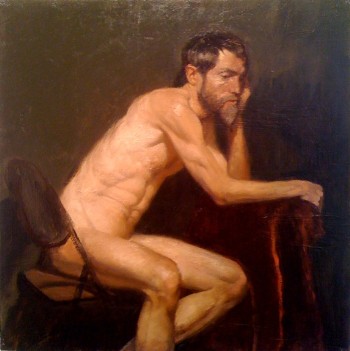

For a wonderful contrast, let’s turn to the quiet, seated nude Max by Lehrer, which draws us in with its stillness. We might completely overlook this one on our first tour of the gallery; it is a small painting, in quiet warm tones, vulnerable and strong, and it doesn’t boss us or hector us. Although he sits on a chair in what looks like a studio, leaning on a high, reddish stool, the man has the feeling of a hermit in a cavern. He is contemplating or meditating. We are being given permission to watch him, if we are smart enough to stay our gaze.

Time and the Figure

Many of Berry’s works in this exhibit seem to show a timeless portrait or else the aftermath of some brutal strain or mutilation. Looking at the aftermath paintings, we hope that whatever it was wasn’t too painful and that the protagonist, and perhaps even the antagonist, have achieved some sort of rest. Though we doubt it.

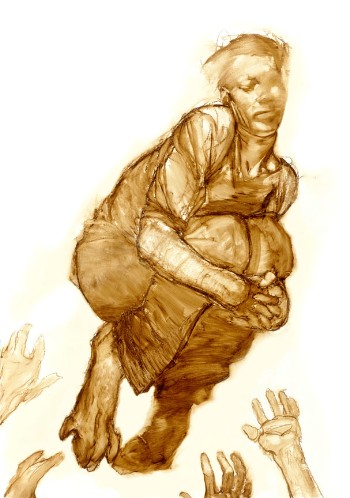

Here, however, in the sepia monotone of Jump! there is no brutality. We are placed in time, in the middle of an action: A boy, or young man, grasps his knees as he jumps or is thrown above a quartet of hands. Trying to make sense of his partly smudged face, it takes us a moment before we notice that he has grotesque paws instead of feet. He is neither all there nor all human. We may be in the middle of things, temporally, but we know there are only a few outcomes: being inhuman, he will fly away; he will fall to ground and escape; he will fall to ground and be caught.

It is the temporal aspect of Lehrer’s The Grownups that lured me into this exhibit. We rarely see, I think, such an odd and present moment in the world of art.

We are here, now, rooted to the present. Two children—a toddler and his slightly older sister—are adrift on a raft heading out to the horizon of a warm, coral sea. Their only provisions are a box, a pillow, a jug of flowers, and a teapot. They seem to be under-prepared for their journey, except for the severe intelligence of the girl and the trepidation and obedience (“Don’t move!” she must have told him) of the boy.

What makes this moment spectacular is that the subsequent adventures, which we can only imagine, are equally important, if unknown. We can and must imagine them. On seeing this canvas, we must write a novel about what will happen, not of what led up to this odd situation—many paintings are aftermath paintings—or not only of what preceded but of what will happen.

I wouldn’t call this work perverted or even “perverted baroque,” as the press release terms Lehrer’s work, but I do think it is marvelously perverse. This is partly because of the palette, which reminds one of the gentlest pictures of and for children, and partly because of all the ambiguities, including that of the leaping fish: is he after the spray of blossoms? Is he coming for the children? Or is he offering himself as food for when they get to their desert island? (She will be Crusoe, her brother Friday . . .) Or does our fish leap simply from some sort of cosmic joy? This picture doesn’t tell us how or what to think or respond. It simply insists that we must.

Eros and the Figure

We cannot see the faces of either of these dancers, in Berry’s My Parents Before I Knew Them, and their heads are dark shadows in a blackish mauve mist. But our parents before we were born are always mysterious figures. Perhaps these two have lost their heads to love. Then, too, the darkness that enshrouds this couple could be there to remind us of the impossibility of imagining the erotic life of our own parents. But there is also a sense of menace here. There is something about the way those globe lights don’t illuminate the mist—combined with the strong and awkward grip of the man’s hand and the unwilling body language of the woman—that makes this seem less like a sexy tango, more like a dance of death.

I think it may be rare that in classical erotic scenes of humans and animals, everyone is having a good time. As far as I can recall, the animals, gods in disguise, are content, while the ravished ladies are appalled or worse.

But here, Lehrer’s Lethargic Picnic, what a marvelous tangle of delighted bodies! Exhausted from sex, the young man dozes, while the leopard drapes himself across his body between the two young women whose arms are linked. Everyone is entwined with everyone. Their ecstasies have not been quiet, however, and now a tiger approaches from the forest hoping to participate, while a crow and a squirrel by the young man’s head are wondering if they, too, can join in.

Oh, this is splendidly erotic, and of course perverse, the scene itself but also the execution: the masterful rendering of the large cats, particularly the tiger, combined with the exquisite modeling of the delicate skin tones of the human forms obscures for a moment the fact that each figure is in a posture that seems at first classical and then twisted and off-kilter. For something has alarmed the women: one points, the other raises her red shirt like a flag, semaphoring out to sea. Even the young man’s foot is pointing into the air. Is there is a hint of his foot being cloven? Or is it just the space between his toes?

The women have just noticed something pinkish in the water, beneath the slanting, rust-colored tree. It’s hard to see from here, but it might just be those children, on their raft, floating out to sea.

Figurative Art

I wonder to what extent it is true that figurative art is more likely to move us than pure abstraction. When swathes of color and line fascinate, is it like the illumination of looking into a good tool box—where we see the elements and instruments and thus the possibilities of art? When raw color astonishes the retina, does it also fully engage the mind? Or do we crave something more, such as the figure, with its intimations of the human condition, to make us weep or wonder?

What about the titles? Calling those drifting children “The Grownups” reminds me how adrift we adults are, and how much our child-selves are (not) steering the boat. The “No Metal Men” brings up all the vulnerability I feel behind my macho exterior…….. and “My Parents Before I knew Them” reminds me that the fierce sexuality I have felt was felt as well by my parents, the tragedy being that they never showed it to me…. This is another wonderful review, bridging the two dimensional world of the visual artist with the heartbeat and breath of narrative.

Oh I think you’re right about the titles, that they are surprising and provocative in the way a good title can, informing our reading of the painting even while nudging us off balance, forcing us to scramble about in our thoughts to make a new kind of sense of things.

Thoughtful review! What the women are noticing in Lehrer’s painting is a clear reference to Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa” in which exhausted shipwreck survivors, composed in the same pyramid-shaped grouping, are signaling a distant ship on the horizon (also visible in Lehrer’s piece) with identical gestures and a very similar piece of fabric flapping in the wind. Intriguing show/reivew.

Oh, this is wonderful. Thanks so much for pointing it out! I agree with what you say, and wonder if this explains that oddly dexterous hand-like foot, also gesturing to the distance.