Classical Music: Gustavissimo – A Dudamel Update

Leonard Bernstein was the most charismatic conductor of the last century. Gustavo Dudamel is the most charismatic of this one – and is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

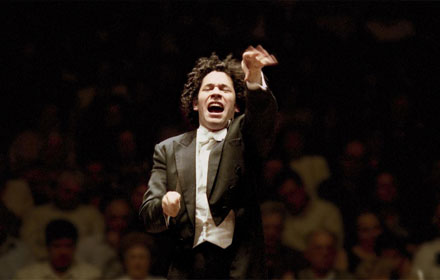

Conductor Gustavo Dudamel in action

By Caldwell Titcomb

In the arena of classical music, the world’s most exciting personage continues to be Gustavo Dudamel, the dynamo from Venezuela, now all of 28. He is a product of the extraordinary youth training program in music that started in his native country back in 1975. Out of this project emerged the Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra (SBYO). Dudamel studied the violin as a youngster, and then conducting at the age of 15. His talent was so great that he was named the SBYO’s music director at the age of 18, a post he still holds.

There has been no such phenomenon since Leonard Bernstein burst on the scene in the 1940s. I wrote about Dudamel and his SBYO on this website when they came to Boston and gave a remarkable concert in Symphony Hall on November 7, 2007. It is time for an update.

In 2004 Dudamel was one of 16 contestants to enter the Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition in Germany, and he won. At that time the seasoned conductor Daniel Barenboim termed him the most exciting new conducting talent he had heard in years, an appraisal echoed by other maestros such as Claudio Abbado and James Levine. Sir Simon Rattle, leader of the Berlin Philharmonic, went so far as to declare Dudamel “the most astonishingly gifted conductor I’ve ever come across.”

As Bernstein had done with Bruno Walter in 1943 with the New York Philharmonic, Dudamel replaced an indisposed conductor in a 2005 London concert with Sweden’s Gothenburg Symphony, and that organization named him Principal Conductor in 2006, with service to run from 2007 for five years. He also made his U.S.debut with the Los Angeles Philharmonic (LAP) in September of 2005. In April of 2007 the LAP announced that Dudamel, then 26, would become its music director on the retirement of Esa-Pekka Salonen in 2009, with a five-year contract. So Dudamel now heads three orchestras.

What Dudamel has done with his SBYO, whose players are all under 25, is absolutely amazing. He has turned that body into the equal of most professional orchestras. And the evidence is confirmed by a series of recordings issued by Deutsche Grammophon, to which he signed as an exclusive artist in 2005.

His first recording with the SBYO (September 2006) paired Beethoven’s Fifth and Seventh symphonies. This was a challenge to the late Carlos Kleiber’s mid-1970s recording of the same pair, often cited by critics as a yardstick achievement. I found the Fifth very good, but not in the top rank. The Seventh, however, is a superb reading of a piece he played live in Boston – the best rendition I’d heard here since Michael Tilson Thomas in 1972. Daniel Barenboim said, “This performance of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony is one of the most exciting I’ve heard in many years,” and this disc won the 2007 Echo Award for “New Artist of the Year.”

He followed that with a stunning Mahler Fifth (May 2007), which holds its own against the versions by Saraste, Eschenbach, and Segerstam. This was the only classical album to gain a place on iTunes’ “Next Big Thing” list. Last year Dudamel switched gears with the colorful “Fiesta,” an album devoted to Silvestre Revueltas and a half dozen lesser known Latin-American composers – Dudamel called it “all about dance, about rhythm.”

Last March saw the release of a Tchaikovsky CD taken from a live concert performance. The Fifth Symphony is a superlative rendition. “The London Telegraph” said that “the playing packs a passionate punch, the aching pangs of the first movement delivered with palpable anguish, the outbursts charged with hot-blooded fury.”

The Times of London stated, “The gorgeously played horn solo in the slow movement was as melancholic as anything in Dostoyevsky.” Indeed, this solo is beautifully phrased and caressed with the utmost nuance; I have never heard it done better. This performance is a worthy companion to the best versions – Koussevitzky, Ormandy, Bernstein, and Monteux. The disc is filled out with a grand reading of the tone poem “Francesca da Rimini,” a powerful work that doesn’t get played often .

There is also an informative 90-minute DVD documentary on Dudamel and the SBYO entitled “The Promise of Music” (2008), which has lots of interviews along with Dudamel rehearsing music by Beethoven, Rossini, Saint-Saëns, Tchaikovsky, and Mahler. That leads into the live 2007 concert that took place in the Beethovenhalle in Bonn, Beethoven’s birthplace. It was courageous to program Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony before an audience that probably knew every note of the piece. But it received a standing ovation, as did the other two pieces on the program (Moncayo’s “Huapango” and Ginastera’s final dance from the ballet “Estancia”). One must remember that all this has been done with a youth orchestra.

That brings us to the start of Dudamel’s tenure with the Los Angeles Philharmonic this fall – the tenth music director in the LAP’s 91-year history. His arrival was a major civic event – as it should have been. “Bienvenido Gustavo” (“Welcome Gustavo”) could be seen all over town – on buses, electric billboards, and T-shirts. It should be remembered that the Venezuelan was coming to a city whose populace is 48% Latino.

The first day of aural celebration came on Saturday, October 3, when a series of musicians performed free before an audience of 18,000 in Hollywood Bowl, with a broadcast for those who couldn’t get in. Just as Bernstein had involved himself in music for young people, Dudamel first ascended the podium to conduct Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” with the two-year-old Youth Orchestra of Los Angeles (YOLA), which serves some 200 pupils, aged 7 to 16, who are given free instruments and lessons in a project modeled on the SBYO out of which Dudamel emerged.

The concert ended with Dudamel leading the LAP in a complete performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, assisted by professional and amateur choruses from the area. As an encore the last section was repeated, accompanied by fireworks. Mark Swed, the critic for the “Los Angeles Times,” wrote, “It felt, at that moment, like the greatest show on earth.” “The New Yorker”’s critic Alex Ross called it “rock-solid” and included it in his list of top ten memorable performances of the year.

The LAP’s official season began in Disney Concert Hall on October 8, with a gala event that PBS televised nationwide on October 21. Most conductors might start such an occasion with a new overture by an American composer. But Dudamel persuaded John Adams, widely considered the foremost living American composer, to come up with a major work. Adams complied with a huge 34-minute work entitled “City Noir.” The composer said that “it was inspired by the peculiar ambience and mood of Los Angeles ‘noir’ films, especially those produced in the late forties and early fifties.”

The piece calls for a large orchestra, including two harps, and features prominent solos for saxophone, trombone, and trumpet. The work is atmospheric and busy, and Dudamel gave it a strong world premiere. (It has also been announced that Dudamel has appointed Adams to the new position of “Creative Chair.”)

Leonard Bernstein was the most charismatic conductor of the last century. Gustavo Dudamel is the most charismatic of this one.

The other item on the program was Mahler’s Symphony No. 1. Dudamel was drawn to this music at an early age, and conducted from memory. Anthony Tommasini of the “New York Times” wrote, “For all the sheer energy of the music-making, here was a probing, rigorous and richly characterized interpretation.” There were some naysayers, such as Ed Siegel of the “Boston Globe,” who found the reading “choppy.” What was he talking about? If he meant the frequent changes of tempo, these are all carefully marked in the score. Those who didn’t hear or tape the performance can make up their own minds since the inaugural concert has just been released on a DVD.

On. November 5-7 Dudamel led the monumental Verdi Requiem, again from memory, and Swed found it “magnificently theatrical,” with “remarkably expressive and vividly dramatic playing from the orchestra.”

As one looks at Dudamel’s programs for the season, one is struck by how imaginative and adventurous they are compared to those in Boston and New York. On November 12-14 Dudamel offered Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, and paired it with the late Italian composer Luciano Berio’s “Rendering,” an amalgamation of the bits that Schubert left for a Tenth Symphony linked by chunks in Berio’s own style. The program also included Berio’s “Folk Songs,” a fresh take on eleven pieces from around the world, sung by Dawn Upshaw. “Dudamel’s performance was terrific,” Swed wrote.

The next week Dudamel separated Mozart’s “Prague” and “Jupiter” Symphonies by Berg’s great memorial 12-tone Violin Concerto (with Gil Shaham as soloist). Swed said that, “somehow, this Venezuelan, who has conducted the Vienna Philharmonic only a time or two,…excavated a long-lost Viennese character out of his new orchestra.” On November 27-29 came a program labeled “West Coast, Left Coast.” Here Dudamel graciously chose the “L.A. Variations” composed in 1996 by his LAP podium predecessor Esa-Pekka Salonen, in which, Swed said, Dudamel “makes Salonen’s machined rhythms danceable.” Marino Formenti played the 1985 Piano Concerto by the late Lou Harrison, and Swed stated that “the wondrous slow movement took my breath away.” Adams’ “City Noir” was repeated from the first concert – “Now it is a big thrill.”

In the spring Dudamel has a program including Chavez’s “Toccata for Percussion,” Lieberson’s heavenly “Neruda Songs” (so beautifully recorded by Levine, the composer’s late wife, and the Boston Symphony), and Bernstein’s “Age of Anxiety” (with Jean-Yves Thibaudet as piano soloist). A week later he will offer Antonio Estévez’s “Cantata Criolla,” joined by the Schola Cantorum of Venezuela in a theatrical presentation with film. His next program presents the world premiere of Stephen Hartke’s “Organ” Symphony followed by Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” Symphony.

In May Dudamel and the LAP will embark on a national tour, visiting San Francisco, Phoenix, Chicago, Nashville, Washington (DC), Philadelphia, Newark and New York City. Alas, they will not be coming to New England. Dudamel will, however, travel here to receive the 2010 Eugene McDermott Award in the Arts at MIT, which carries a $75,000 prize. He will visit MIT’s Media Lab (which has a brand new building all its own). He says he is eager to see “the wonderful music program and the Media Lab firsthand – the next generation in music and technology in one place.” He will also conduct an open rehearsal with the MIT Symphony Orchestra on April 16.

In addition to the honors mentioned above, Dudamel is the recipient of the Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts (Spain), the Royal Philharmonic Society Music Award for Young Artists (England), the Premio de la Latinidad, the Glenn Gould Prize (Toronto), and the “Q Prize” from Harvard University for extraordinary service to children. “Time” magazine last April named him one of the 100 most influential people, and this October he was proclaimed by “Esquire” magazine one of “the 75 best people in the world” for showing “why classical music has a future.” “The New York Times” on November 13 accorded Dudamel the honor of a special feature on its front page.

And what do his Philharmonic players think of their new boss? The orchestra’s concertmaster, Martin Chalifour, commented, “The great thing about Gustavo is that he has a great technique; he’s very clear with the baton. And he’s absolutely driven to find the emotional heart of the music.”

It is a treat to watch his visage and gestures as he conducts on the podium. The LAP engineered a tremendous coup in snaring him. Leonard Bernstein was the most charismatic conductor of the last century. Gustavo Dudamel is the most charismatic of this one – and is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

Tagged: Caldwell-Titcomb, Classical Music, Gustavo Dudame, Leonard Bernstein, conductor