Theater Commentary: Happy 400th Birthday to Ben Jonson’s “Catiline: His Conspiracy”

Multiple Google searches suggest that no one is celebrating the 400th anniversary of the second of Ben Jonson’s Roman tragedies. But attention should be paid to this awkward but powerful script. Filled with perceptive realpolitik and rich poetry, it proffers a brilliant, seriocomic meditation on political gangsterism.

By Bill Marx

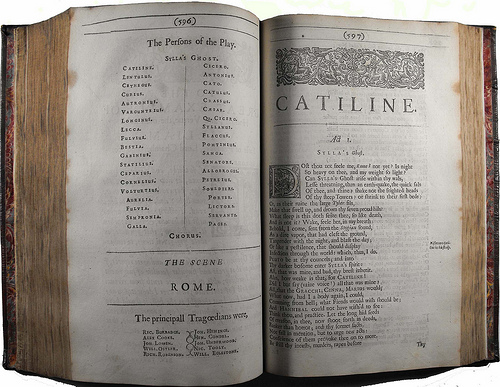

What does a playwright do after writing one of the greatest comedies in the English language? If you are Ben Jonson, you try to top The Alchemist by penning the second of your Roman tragedies, Catiline: His Conspiracy, which premiered 400 years ago. He didn’t succeed. In fact, the drama was met with hoots of derision when it opened, and the drama has drifted into obscurity in the modern era, though S. T. Coleridge was an admirer, and the play was popular in Stuart England. Exasperated by Catiline‘s initial reception, Jonson appealed to “the Reader extraordinary” in the future to appreciate the play’s merit.

I am one of those readers reporting for duty. Attention should be paid to Catiline on the anniversary of its production; the script is awkward but powerful, filled with perceptive realpolitik and rich poetry. It proffers a seriocomic meditation on political gangsterism worthy of a Quentin Tarantino touched by lyrical genius, a sharp fantasia on our ever-evolving appetites for extremism. For those who admire Jonson, it offers a particularly revealing side of his paradoxical (didactic meets Dada) greatness.

I am not arguing that Catiline is a neglected masterpiece. In many ways Jonson’s earlier tragedy, 1603’s Sejanus: His Fall, is superior theater, because it buffs to murderous perfection Jonson’s steely vision of roiling authoritarian corruption: the tyrannical Roman emperor Tiberius lures his ambitious second-in-command, Sejanus, into a homicidal trap in order to replace him with a less threatening sycophant. The few citizens longing for freedom comment with ineffectual despair on the “show trial” of absolute command and the decadent fashions of the court.

In 1611’s Catiline, Jonson offers the counter view, and it is more static. The plot to violently destroy the Roman republic is defeated by Cicero, who in the senate delivers an inspiring exhortation (about 300 lines long and based on the politician and philosopher’s writings) that sends the traitors packing, their eradication assured. Cicero’s super-bloviation is one reason Catiline failed badly when it was first staged: the audience resented having to sit through a long, long lecture.

Some critics see Cicero as an egomaniac, an idealized stand-in for Jonson himself. For me, the character is the playwright’s bookish version of Prospero—Cicero practices a kind of linguistic magic, a spell cast by reason, sanity, and courage. It is Jonson’s over-the-top hymn of praise to the efficacy of language and his classical heroes, his prayer that words can protect the state from self-inflicted atrocity.

What unites Jonson’s comedies and tragedies is that they offer moral critiques of our public and private appetites. As in his comedies, Jonson dramatizes in glorious technicolor our cravings for power, control, violence, and hedonism. Because the stakes are so much greater, the hyperbolic dreams in the tragedies are bloodier and more terrible—the imagination is infected to the point of murderous absurdity. It is at that surreal null point that the comedies and tragedies meet — The Alchemist‘s Epicure Mammon’s desire for ever-expanding desire, for non-stop want, is at the center of Jonson’s vision.

Thus Catiline and what he admits are “Th’ rash, th’ ambitious, needy, desperate,/ Foolish, and wretched, ev’n to the dregs of mankind” are less interested in working out a pragmatic strategy than in whipping up a rhetoric of pure mayhem. For example, one whacked-out conspirator, Cethegus, voices an urge to kill that ranges into hyperbolic realms of carnage:

Swim to my ends, through bloud; or build a bridge

of carcasses; make on, upon the heads

Of men, strooke down, like piles; to reach the lives

Of those remaine, and stand.

We never see Cethegus hurt a fly, but that is Jonson’s point—he is all talk, his need to destroy a rhetorical end in itself, rather than, as it is in the plays of Christopher Marlowe, a means toward winning absolute power. What would happen if Cethegus ever got his hands on an army? Perhaps build mountains of the dead that would anticipate the holocausts of the twentieth century. One striking scene in Catiline has the lead baddie and the other patrician rebels toast to their fight for unending pleasure, for “freedome and community,” with the blood of a slave who was killed for the occasion. The tableau captures (like an editorial cartoon) naked political barbarity. The marvelous opening scene features a ghost that breathes chaos into the mind of Catiline: “The ruine of thy country: thou wert built/ For such a worke, and born for no lesse guilt … That is thy act, or none.” Some men and women are cursed, via dybbuk, to generate destruction.

Also, Jonson was too good a dramatist not to put some flaws into his representative of virtue, Cicero. For example, he is willing to use spies (which Jonson despised) and bribes to ferret out information needed to defeat the power grab. Catiline calls Cicero a “boasting, insolent tongue-man,” and there is some truth to this, even though his words are weapons that maintain the endangered political order. (One of Jonson’s biggest missed opportunities is that he doesn’t give the villain any down-and-dirty rejoinders to Cicero’s rhetorical assault — he slinks off in defeat.) When do questionable means, used to serve the good, become self-defeating ends?

One of the reasons academics and audiences don’t get Sejanus and Catiline can be attributed to Jonson’s rage for order, his deep love of classicism. He called the scripts tragedies, even congratulating himself for writing a chorus into Catiline. Scholars and theater directors waste most of their time pointing out how these ‘Neoclassical’ plays fall short of tragic expectations –- there’s no fall from heights, no catharsis, no evidence of self-discovery through suffering, etc. –- rather than trying to see what Jonson is up to. For me, his “tragedies” are experiments in satiric political melodrama.

Jonson’s tragedies are a response to the Shakespearean approach — they need to be appreciated on their own merits. As Coleridge wrote in his copy of Catiline: “A fondness for judging one work by comparison with others, perhaps altogether of a different Class, argues for a vulgar Taste. Yet it is chiefly on this Principle that the Catiline has been rated so low. –Take it and Sejanus, as compositions of a particular kind — viz. as a mode of relating great historical events in the liveliest and most interesting manner, and I cannot help wishing that we had whole Volumes of such Plays. We might as rationally expect the excitement of the Vicar of Wakefield from Goldsmith’s History of England, as that of Lear, Othello &c from the Sejanus & Catiline.” This sentiment is worth remembering when considering the plays of any of Shakespeare’s contemporaries.

I know for a fact that Sejanus’ dark vision of politics succeeds on stage. In 2005 I saw the Royal Shakespeare Company’s (RSC’s) terrific production of Sejanus (to mark the 400th Anniversary of the Gunpowder Plot). After the show, I asked its director Gregory Doran about the possibilities of him and the RSC staging Catiline. He told me was eager to produce it, but immediately began to laugh and added that there would have to be cuts. (So far that production has not come about, alas. I would fly to England to see it.) Script excisions and modifications would be fine. Perhaps as rebuttal to Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Jonson stages the bloody end of Catiline and his follow conspirators off-stage—seventeenth century productions visualized the battle.

The mention of Julius Caesar brings up another interesting facet of Catiline‘s examination of rebellion. Jonson makes it clear that Caesar is a cohort of Catiline’s, an admirer of the plot and its dedication to aristocratic dictatorship. Once he sees that Cicero has carried the day in the senate, Caesar publicly backs away from his support of Catiline—though Jonson could count on his audience to know that Caesar would later come to power and end the republic. What’s interesting is that Cicero knows that Caesar was part of the conspiracy, but he does not act. This is a tragic mistake, an arrogant miscalculation: Did he presumptuously believe that his words had somehow changed Caesar? It is foreshadowed at one point during Cicero’s speech in the senate:

Not only the grown evil that now is sprung

And sprouted forth would be pluck’d up and weeded . . .

But the main peril would bide still enclos’d

Deep in the veins and bowels of the state,

As human bodies laboring with fevers.

Jonson is adapting the words of Cicero, but the treatment of Caesar at the end of the play smacks of the dramatist’s customary wiles: evil has been vanquished today, but that triumph may only mask the workings of a deeper and more powerful malevolence. Perhaps Caesar has learned from this set-back, the fledgling germs of ambition evolving into a stronger disease. The bottom line for this playwright is that, no matter how eloquent, the wise man should always keep looking over his shoulder. I doubt I will ever see a production of Catiline, but there is ample proof in the reading that one of England’s finest dramatists had not strayed too far from his creative peak when he wrote this flawed play about the virus of anarchy.

Jonsonians and Other Lovers of Elizabethan Drama and Verse Rejoice!

There will be more Jonson for the “Reader extraordinary” to wallow in — two major publications are forthcoming. One of the world’s leading Jonson scholars, Ian Donaldson, will publish Ben Jonson: A Life (Oxford University Press), the first major biography of the dramatist/poet since David Riggs’ respectable but uninspiring Ben Jonson in 1989. I have been waiting years for Donaldson’s volume, and there will be a review on The Fuse. Donaldson is also one of a team of editors who have completed The Cambridge Edition of the Complete Works of Ben Jonson (Cambridge University Press), which is slated for a January 2012 release. The seven volume set will sell for $900, a steep price. But an electronic version is promised in 2013, and perhaps an inexpensive paperback edition may come along.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse and a long-time Jonsonian. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Ben Jonson, Catiline, Elizabethan drama, Ian Donaldson, Julius Caesar, Sejanus, tragedy

Dear Bill,

I read your article with great interest. I wanted to point out that, as far as I’m concerned, I think I did properly celebrate Catiline‘s 400th anniversary by publishing its first Italian edition (introduction, English text + facing Italian translation, notes) earlier this year.

I would also very much like to see it staged but I don’t know if it will ever happen.

If you want to check out my edition, please see:

http://domenicolovascio.blogspot.com/.

I don’t know if you can read Italian. If this is the case and you are interested in reviewing the book, I will be extremely happy to send you a copy.

Best wishes,

Domenico

Dear Domenico,

Thanks for telling me about your edition of Catiline — I don’t read Italian, so I will not be able to review it, but I am happy to hear that Jonson’s final tragedy received recognition on its 400th birthday. I don’t think it will be staged in English, but your edition offers Italian directors an opportunity to tackle this fascinating text.

Best,

Bill