Book Review: To End All Wars

“To End All Wars” embodies its themes –- the decline of the aristocracy, the rise of propaganda, the transformation of war-making, the heroism of resistance –- so skillfully in a dozen or so major characters and another dozen minor ones that this history of the First World War reads like a lively group biography.

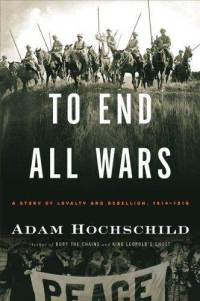

To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914-1919 by Adam Hochschild. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 448 pages, $28.

Reviewed by George Scialabba

History, observed Gibbon, is a record of the crimes and follies of humankind. The historiography of the twentieth century’s two global wars is, accordingly, extremely rich. Adam Hochschild’s vivid and poignant To End All Wars does not add any new crimes or follies to the already crowded annals of the First World War, but it is a welcome addition to the literature all the same.

Words like “watershed” or “turning point” are easy to deploy but hard to justify –- except in the case of World War I. Like few other episodes –- the fall of Rome, the Black Death, the Protestant Reformation, the French Revolution –- it really did leave a different world in its wake. The technology of mass destruction was perhaps the most obvious respect. Barbed wire, trench warfare, the machine gun, the tank, poison gas, artillery barrages, and aerial bombardment all meant that war would no longer evoke enthusiastic reactions like that of one characteristically brainless young aristocrat in the first weeks of the war: “It is all the best fun. I have never felt so well, or so happy, or enjoyed anything so much.” Such upper-class twits were killed off even more rapidly than the plowboys and factory workers who followed them into the maw of the new industrial killing machines. War would no longer be noble sport; it was professionalized.

And so, more subtly but no less fatefully, was government. The technology of mass persuasion (otherwise known as propaganda or indoctrination) was first introduced not by the totalitarian regimes of the interwar period but by the democracies during World War I. As John Buchan, the British Empire’s tireless propagandist-in-chief, put it: “So far as Britain is concerned, the war could not have been fought for one month without its newspapers.” The same was true of Germany and France. The first total war imposed unprecedented burdens on the population and therefore required unprecedented lying and coercion on the part of governments to preempt or suppress dissent. They rose to this challenge brilliantly, cajoling newspaper owners, cultivating friendly journalists, subsidizing “patriotic” writers, speakers, and film-makers, prohibiting or sabotaging antiwar meetings and publications, and harassing or, when necessary, imprisoning critics. Government was no longer largely a hobby for the more earnest, non-fox-hunting members of the aristocracy. It became public administration, one of the social sciences.

Hochschild does not harp on these epochal changes, but his dense, beautifully integrated narrative illustrates them very effectively. He has embodied his themes – the decline of the aristocracy, the rise of propaganda, the transformation of war-making, the heroism of resistance – so skillfully in a dozen or so major characters and another dozen minor ones that To End All Wars reads like a lively group biography.

At the center of the story are three relationships and one rivalry. Sir John French was a genial cavalry officer who rose to become the first commander-in-chief of England’s forces in World War I. His older sister, Charlotte Despard, was a socialist, feminist, and pacifist who was nevertheless unquenchably fond of her pleasure-loving, free-spending brother, whom she often rescued from debt and just as often embarrassed by going to prison for her antiwar activities. Alfred Milner was a wealthy and talented civil servant who rose rapidly to Lloyd George’s right hand in the War Cabinet and, after the war, to colonial secretary. Violet Cecil, the dazzling wife of a colorless scion of one of England’s great families, fell in love with Milner in South Africa and carried on a concealed affair with him for two decades, until they could marry. Keir Hardie worked in the coal mines as a boy, was fired for attempting to organize a union, and became one of Britain’s greatest labor agitators and a member of Parliament. Hardie and Sylvia Pankhurst, one of England’s leading feminists, also carried on a long secret (Hardie was married) love affair. The rivalry was between Sir John French and Sir Douglas Haig, a puritanical and pigheaded Scotsman who was nonetheless just as besotted with obsolete cavalry maneuvers as French. Haig was a ruthless bureaucratic infighter who managed to supplant the hapless French as commander-in-chief, whereupon he performed equally disastrously.

The blood-curdling callousness and incompetence of military commanders on both sides has always been a leading theme of World War I historiography. A few historians have recently disagreed, as historians inevitably will whenever there is a longstanding consensus to disagree with. But Haig’s place in the military hall of infamy seems secure. Dining on foie gras and Chateau Lafitte supplied by his friend the banker Lord Rothschild, arranging favorable publicity for himself with his friend the newspaper magnate Lord Northcliffe, endlessly lobbying the King to keep his job over the objections of Lloyd George and Milner, Haig apparently had little concern left to spare for his troops, whom he regularly sent to their death by the thousands to gain a few hundred yards of shell-pocked, barbed-wire-strewn terrain. After the war, in grateful recognition of Haig’s murderous bungling, Parliament awarded him a peerage and ten million dollars.

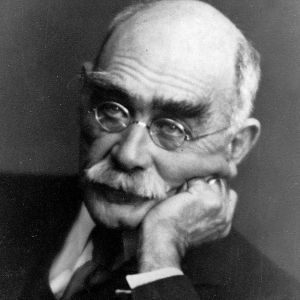

Many of the nearly 25 million soldiers and civilians who died in the course of the war died anonymously. But a few deaths gained a very high profile. Violet Cecil’s son was missing in action, as was her good friend Rudyard Kipling’s. The War Office spared no effort to find them, without success. Hochschild’s extended portrayal of Violet’s and Kipling’s grief is affecting, even if their favored treatment was infuriating.

Just as infuriating was the harsh treatment meted out to conscientious objectors and antiwar activists, which frequently broke their health after only a few months in prison. But then, at least in wartime, the actions of nearly all governments are nearly always infuriating, as Hochschild liberally illustrates. For example, he reproduces a scathing letter to an English newspaper from a corporal, describing the outlandish numbers of men assigned as officers’ servants and grooms – a colossal waste of manpower. Naturally, the writer was court-martialed. Class privileges were beyond discussion, even if they hampered the war effort.

Hochschild’s dramatis personae are mainly English, but the focus becomes more international late in the book, as the specter of socialist revolution began to haunt the warring governments. In the weeks before the war, left-wing parties throughout Europe had vowed to refuse their support. They gave in to government pressure and the martial enthusiasm of their members, who believed, like everyone else, that the war would be short and glorious. But as the slaughter at the front and deprivation at home dragged on, talk of revolution began to be heard. When the Russian army disintegrated and the Bolsheviks took power in late 1917, the ruling classes of England, France, and Germany began to panic. The English formulated plans to send troops to fight in the Russian civil war. The French sent cavalry divisions home from the front for use against strikers. As soon as the Armistice was signed, the English and French allowed Germany to send thousands of soldiers and machine guns home to use against rebellious workers. Notwithstanding their wartime slogans, all governments recognized their paramount interest in preventing genuine democracy. In that, they succeeded, however abysmally they failed at everything else connected with the war (including the peace treaty that concluded it, which even Milner called “a Peace to end Peace”).

The balance sheet of “this glorious delicious war,” as that bloody-minded fool Winston Churchill pronounced it at its outset, was fantastically, incalculably negative, leading directly or indirectly to totalitarianism, genocide, and an even more insanely destructive war. From its bitterly ironic title to its somberly elegiac ending, To End All Wars tells this story powerfully and sensitively, forcing us to swallow its bitterness, as we all must do again and again if we are ever to learn wisdom.

Tagged: 1914-1919, Adam Hochschild, To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion

Thank you for your review.

A question: Christopher Hitchens, in his NY Times book review piece about Hochschild’s book, writes that Hochschild “approaches a truly arresting realization: Nazism can perhaps be avoided, but only on condition that German militarism is not too heavily defeated on the battlefield.”

Is that truly Hochschild’s argument? Or is it Hitchens lazy misreading, as I would not be surprised to hear.

In either case, there is a strong counter-argument: that if the allies had simply taken Berlin, rather than settling for an armistice, no one, not even Hitler, could have pretended there had been a “stab in the back” by the Jews. Germany would have lost pure & simple.

Does Hochschild weigh in on this? Do you, after reading him, have any thoughts?

Harvey:

It’s not exactly Hochschild’s argument. (Actually, I can’t tell whether it’s Hitchens’s either.) He doesn’t, in fact, do more than discuss the question in passing. He certainly does say that the war and the Versailles settlement fostered Nazism. And he does point out that it was the American intervention that, by tipping the military balance, put the French in a position to dictate those harsh terms. But mostly Hochschild points to the war itself — and specifically, to the cynicism bred by the relentless propaganda of all sides and to the falling of moral barriers to mass slaughter, particularly of civilians — as making the subsequent outburst of insanity that much harder to avoid.

There’s a passage on page 373 of the book that says all this — pretty eloquently and sensibly, in my opinion.

Can’t resist a bit of the counterfactual here: I haven’t managed to convince myself the world would have been worse had Germany won World War I. Whenever I think about it, I have to remind myself of the ways the U.S. was provoked beyond measure into fighting, by prussian aggression. And still I wonder.