Fuse Classical Music Review: Boston Early Music Festival, Part Two, Exhibition and The Boston Camerata

BEMF is, quite simply, paradise for those who love early music, and they seem to be a different audience than those who show up for, say, the Boston Symphony or any of the excellent chamber music groups around town.

By Susan Miron.

While classical music, especially orchestras, has been lamenting for decades about finding audiences, Early Music, or at least the renowned Boston Early Music Festival has no such problem. Perform at this festival—any time (9:30 a.m., 2 p.m. 5 p.m. 11 p.m.)—and you will get a good audience. (An international crowd of 15,000 people are here for the festival.) This is, quite simply, paradise for those who love early music, and they seem to be a different audience than those who show up for, say, the Boston Symphony or any of the excellent chamber music groups around town. There are enough concerts in the Boston area, quite amazingly, to satisfy yearnings for early music all year long.

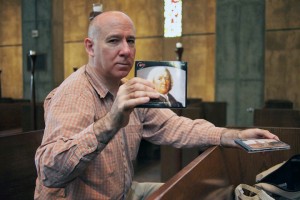

Keyboard master Peter Watchorn — The BEMF offered an amazing opportunity to watch him improvise on the harpsichord.

Wednesday, I was able to hear three totally different concerts, two at Jordan Hall and one that I accidentally—and happily—walked into at the Exhibition Hall on the Radisson’s 6th Floor, a haven for instrument makers, CD sellers (and buyers), sheet music, and specialty books (there were 81 exhibitors). The room into which I stumbled was packed; I sat on the floor listening to the British harpsichordist Peter Watchorn playing Bach on the harpsichord. Mr. Watchorn’s years of daily improvisation at the keyboard made his approach unusually fascinating.

After playing movements from Bach’s French Suites (his CDs of them will be out in September), he showed us how this worked. He simply sat, played a theme of his own making, and went on improvising for a good 10 minutes. For a musician like myself, who simply was never encouraged or taught to improvise and who can barely imagine doing so, it was a extraordinary experience. This, he mused, provides an inkling into J. S. Bach’s amazing gift for improvising, the imagination that inspired Bach to compose cantatas every single week. Bach’s Six French Suites (for keyboard like his Six English Suites) were, he feels, “Bach’s laboratory,” teaching tools for some of (21) children. No other Bach suite, he noted, has this diversity, and their improvisatory element makes them a living, breathing thing.

The mezzanine also had many instrument makers. If you liked recorders, this must have been heaven. I found a half dozen new, smallish harps, most inaccessible (up against a wall with no one in charge). Perhaps they were there as a strictly decorative matter. I was needing a break from recorders, so I took a walk and listened in on other concerts until at 8 p.m when I showed up for The Boston Camerata’s charming program, “The Morphing Beast: “Le Roman de Fauvel.”

I hadn’t heard The Boston Camerata until this past year, but after hearing four concerts, I wouldn’t miss them for the world. Their program ingeniously opened with “Le Bestiaire D’Amour,” seven songs and pieces performed by The Camerata’s Music Director and long-time star, Anna Azéma, and an extraordinary, 22-string harpist and viellist, Shira Kammen. Joel Cohen may have stepped down as Music Director, but he always seems to make a welcome and newsy appearance, as he did here, narrating and playing several instruments. Mr. Cohen edited and conceived this concert version, adapting it from a manuscript in the Biblioteque Nationale de France, Paris. The Camerata first began recorded this work 21 years ago; in this program, five of the original six members were performing.

“Le Roman De Fauvel; A Medieval fable in poetry and music,” based on a scurrilous, satirical poem the Roman de Fauvel, which surfaced in Paris in 1310, is one of the Camerata’s classic shows. It shows no sign of getting old. As Ms. Azéma writes, “In my opinion, Fauvel‘s truculent criticism of hypocrisy and greed in public life continues to be a relevant as the headlines in today’s newspaper.” Fauvel, a violently anti-establishment tome that began life in the literary underground, is filled with diverse moods and tones, and the piece contains music that reflects the eclectic range of its time: Gregorian changes, obscene street calls, polyphony in the avant-garde Ars Nova style, and courtly songs. Its central metaphor is a horse named Fauvel, who represents the spiritual rot of church and state. He is, as Mr. Cohen points out, “a nefarious creature . . . who represents moral stench . . . whose story creates a theatre of the mind.” At different times in this captivating piece, Fauvel morphs into a love-sick horse, then a party horse.”

The illustrations on the screen and the lovely music made this concert one of the best of the many I listened to during the festival week. It also makes this presentation of Fauvel a prototype for the Gesamptkunstwerk that Richard Wagner dreamed of five centuries later. The performances, especially of Ms. Azéma, were wonderful, and I hope the group repeats this piece one day soon. Ms. Azéma and her colleagues in the Camerata do just about everything right—and beautifully to boot. They even had a recorder that didn’t bother my ears.

.

Tagged: Boston Early Music Festival, Peter Watchorn, The Boston Camerata