Arts Remembrance: “Shooting Is the Research” — Frederick Wiseman in His Own Words

By Ed Symkus

To watch a Frederick Wiseman documentary is to see a subject or topic through the filmmaker’s eyes.

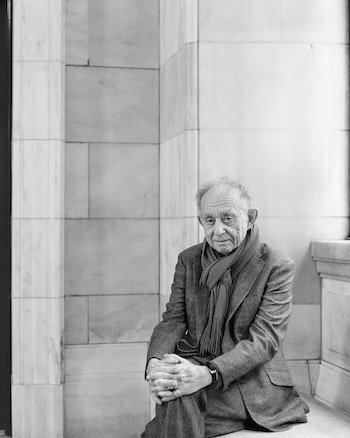

The late Frederick Wiseman at the New York Public Library, 2017. Photo: Wolfgang Wesener

Boston native, longtime Cambridge and Paris resident, and documentarian Frederick Wiseman died on Sunday (Feb. 16) at the age of 96. Over the past six decades, the prolific filmmaker directed, produced, and edited 40 feature-length documentaries that varied as much in running time – the shortest was High School (75 minutes), the longest was Near Death (358 minutes) – as they did in topics – the titles Basic Training, Juvenile Court, Welfare, Racetrack, Multi-Handicapped, Central Park, Ballet, Boxing Gym, and City Hall provide an idea of their scope.

But these aren’t what many people think of as conventional representatives of the genre. Wiseman’s films do not typically feature people talking about or being questioned about specific subjects, then present said subjects on-camera. Rather, they are laid-back, personal affairs, in which he and his camera become observers of people and activities in action. To watch a Wiseman documentary is to see a subject or topic through his eyes. He would get permission to become a non-intrusive part of what was going on, just let things happen, then fashion his footage into an incisive and immersive exploration of that subject or topic in the editing room.

The documentaries came out of Wiseman’s own distribution company Zipporah Films, were initially seen on PBS stations, and there couldn’t have been enough mantels in his home for the number of honors they garnered, from organizations including the Academy Awards, Boston Society of Film Critics, Cannes Film Festival, Critics’ Choice Awards, Emmy Awards, International Documentary Association, Peabody Awards, Venice Film Festival, and more.

I had the privilege and pleasure of sitting down to talk with Wiseman on four occasions between 2001 and 2015. In commemoration of our wide-ranging discussions and of Wiseman’s enlightening, compelling, sometimes disturbing, sometimes entertaining output, I’ve chosen specific moments from those interviews that have him telling pieces of his story in his own words.

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh and other city servants in a scene from 2020’s City Hall. Photo: Stills/Photographs courtesy of Zipporah Films, Inc.

AF: What interested you in film?

Frederick Wiseman: I was a film nut. When I got out of the army, I lived in Paris for a couple of years, and went to the movies a lot. I always wanted to make movies but I didn’t do anything about it.

AF: You were studying law at one point.

Wiseman: I went to law school, but I never practiced. I didn’t like it. I was bored out of my mind. I never went to class in law school. I read novels instead. Later on, I taught at B.U. Law School for a while. But I intensely disliked teaching law, and I reached the witching age of 30, and figured I better do something I like.

AF: What led you to making your first film, Titicut Follies?

Wiseman: When I taught at B.U. Law School, I taught a course in legal medicine. As part of that course, I took students on field trips. I thought it would be interesting for the students to get beyond the abstractions of appellate court decisions, and see what it was like when someone was sentenced to a mental hospital or a prison for the criminally insane. I took them to Walpole and parole board hearings and Bridgewater State Hospital. So, when I had it with teaching law and wanted to follow up on my interest in movies, I thought Bridgewater might make a good movie.

AF: And you just jumped right in?

Wiseman: I couldn’t afford film school, so I worked on a production of a movie and that sort of demystified the process for me. I worked on a movie called The Cool World, by Shirley Clarke, about gangs in Harlem. It was a fiction movie, but had a partially documentary aspect. So, I figured, why not.

AF: Did you know you had amazing footage while you were shooting Titicut Follies?

Wiseman: Well, I thought it was good footage. I knew it was interesting and unusual, for sure.

AF: Have you been shocked by what you’ve seen through the camera over the years?

Wiseman Of course, but not always. I’m as interested in people doing nice things as I am in their doing awful things. I think the films show that. In the film I did at the Beth Israel, Near Death, the doctors and nurses were great. And I’ve had some fun stuff in them. So, I don’t view my films as exposé films. A place like Bridgewater was a horrible place. But Beth Israel, and the place where I made Juvenile Court in Memphis, and lots of others, the people who run them are trying very hard to do a good job. I think it’s just as important to show that as to show the terrible stuff.

A still from 1999’s Belfast, Maine. Photo: Stills/Photographs courtesy of Zipporah Films, Inc.

AF: Has it been easy to get these films made?

Wiseman: Permission, with one or two exceptions, has been easy, when I had the right approach. A cold approach didn’t work, but when I got somebody to vouch for me, it worked very well. That part has always been easy; it’s usually the result of a phone call or a letter, and a visit. What I always try to do is, whenever I ask permission to make a film, I offer to show the people my previous films. I think it’s important to make absolutely full disclosure. I always provide them with a list of films I’ve made and I ask which they’d like to see. Sometimes they see one of them, sometimes they see a bunch, occasionally they don’t see any. I have no interest in trying to deceive anybody, so I always try to do it straightforwardly. But the money is always a problem. People think I get the money easily, but I don’t. PBS has been very supportive of me over the years, but I get about 25 percent of the budget from PBS. The rest is from foundations.

AF: You have a reputation for doing your research as you’re making your films, not in advance.

Wiseman: Yes, shooting is the research. Since none of the events in my films are staged, I find there’s not much point in spending a lot of time in the place because nothing that I’m seeing will be repeated exactly the way I saw it. So, what I try to do in advance is get a sense of the geography and a sense of the routine before I start shooting. When I made At Berkeley, I knew where the director’s office was, and I knew where the entrances were, and I knew what time the place opens up. I can usually do that in a day.

AF: For At Berkeley, how did you get people to relax and be comfortable around cameras?

Wiseman: I didn’t do anything differently. In my experience, the worst thing you can do is to try and do something, because that makes people very self-conscious. The only formal technique that I’m aware of is that I don’t bullshit people. I try to be very straightforward about what I’m doing. I always explain what I’m doing, and how it’s going to be used.

AF: What do you tell them you were doing on that film?

Wiseman: I told them exactly what I thought I was doing – I’m making a movie for PBS, and maybe for theatrical distribution, about the University of California at Berkeley, and I’m spending three months here, accumulating a lot of footage. I don’t know what the themes of film are gonna be yet. That all has the charm of being true. I discover the film in the editing, and I always have. If anybody doesn’t want to be shot, they should tell me now, and then the class begins.

AF: How would you describe the Fred Wiseman technique of filmmaking?

Wiseman: The technique is always the same. It’s a small crew. There are three of us – me on sound, John Davey’s behind the camera – and we only use one camera – and an assistant. No interviews, no lights. You just hang around. I like to think that I’ve learned something over the course of making these films for close to 50 years, and I like to think that what I’ve learned is in whatever film I’m currently working on. So, you hang around, shoot a lot of film, figure it out on the editing. That’s the short, general statement of the technique. Of course, there’s a wide variety of human behavior out there. So, one of my interests is in documenting as much of it as I can.

AF: I’d heard about In Jackson Heights quite a while ago. How long did you have the idea before you made it?

Wiseman: When I’m finishing a movie, in order to avoid postpartum depression, I have to figure out what I’m gonna do next. Not so much during the editing, but by the time I reach the mix and the color grading. Because to be working keeps me off the street. I sort of have a running list of ideas in my head. Sometimes I revert to that list, but sometimes something will just pop up. I had initially thought of In Jackson Heights in 2007, and I was going to do it, but then I got permission to do La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet, and I figured Jackson Heights would still be there, but the permission from the Paris Opera Ballet might not. So, I did that, then that led to some other films in France and then At Berkeley in America. Then, when I was finishing National Gallery in the winter of 2014, I was thinking about what to do next, and I remembered In Jackson Heights.

A still from 1975’s Welfare. Stills/Photographs courtesy of Zipporah Films, Inc.

AF: Do you approach the process of editing differently on different films?

Wiseman: It’s always the same. I look at all the rushes. That takes six or seven weeks. I make notes about the sequences, then I put aside roughly 40 to 50 percent of them, and I edit the ones that I think I might want to use in the film, without even thinking about structure. It’s only when I have all of the ones edited that I think I might use that I begin to work on structure. At that point, those candidate sequences are in usable form. I have no idea in advance what the themes are going to be. It’s only after I’ve edited all sequences I might use that the themes begin to emerge. I make the first assembly in three or four days, and the first version comes out to be about 40- or 50-minutes longer than the final film. Then I can make the changes very quickly about what I want to use and the order in which I want to use it. That might take another four or five weeks. That’s when I’m figuring out the themes, the point of view, and the rhythm.

AF: Is anyone watching your back?

Wiseman: When I used to edit on film, I worked alone. Now that I’m editing digitally, I have an assistant. But I never show it to anybody till it’s finished. I make the decisions.

AF: Do you have a specific audience in mind when making these films?

Wiseman: I make them for myself, I hope not out of arrogance, but I don’t know how to think about an audience. I have no idea who’s watching my films. It’s a fantasy. People that say they know their audience … that’s bullshit. It’s nonsense. Even when I get feedback from viewers, I don’t know what’s representative. I have to make the movie to meet my own standards, because if I start thinking about other people, one, it’s a fantasy and two, I don’t know how to do it.

AF: Aside from the money issues, has it gotten any easier to make these films?

Wiseman: It’s very interesting work. I don’t find it to be a strain. I love doing it. I love making documentaries because it’s intellectually demanding and physically demanding. You have to be in shape, both to run around and make the movies, and then to sit for 10 months in a chair editing them. But it’s fun because it’s completely absorbing.

Ed Symkus is a Boston native and Emerson College graduate. He went to Woodstock, has interviewed Gus Van Sant, Billy Crudup, Doris Wishman, and Wes Anderson, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, Nantucket, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, Capri, and the Isle of Wight with his wife Lisa.