Arts Commentary: From the Editor’s Desk — By Popular Demand, 2026

Back in February of 2024 I began to write a weekly column for the newsletter on Substack. A few readers have asked that I post these opinion pieces in the magazine.

Here is a selection of Favorite Columns of 2024

Here is a selection of Favorite Columns of 2025

Below is a selection of my top picks of 2026.

—Bill Marx, Editor-in-Chief

March 11, 2026

Dramatist Bertolt Brecht and critic/translator Eric Bentley in 1948. Photo: American Theater

In his 1960 essay “The Pro and Con of Political Theatre,” critic Eric Bentley points out that “the Germans have a term, Zeitstück, for a play that tries to cope with the leading problem of the day. It will, of course, be of the highest interest to see what the playwright considers that problem to be.” The use of “he” is antiquated, but Bentley’s comment on the public responsibility of serious dramatists remains salient. What, for our playwrights, is “the problem of the day”? And how are they addressing it?

Because of the Cold War, Bentley believed that the issue was war, the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki having raised the possibility of nuclear annihilation. America and Israel’s war with Iran also heightens the chances of a thermonuclear war; that nightmare, largely unaddressed in our theaters, remains as urgent as ever. As for our current crop of dramatists, I can’t tell you what they think is “the problem of the day,” though Company One’s lively production of the climate crisis play You Are Cordially Invited to the End of the World! may be onto something.

Bentley feared that the prospect of nuclear armageddon would spawn a literature of “terror and defeat, which is to say, of nihilism.” He was wrong in thinking that. Not much chance that American theater would swing that way. The critic ended his essay by calling for a “reorientation … [that would] entail placing the question of slavery and freedom again at the center of liberal (radical, revolutionary) activity, especially intellectual activity. For, as Camus said in Stockholm, ‘the nobility of our calling will always be rooted in two commitments … the service of truth and the service of freedom.’” For our playwrights and a number of America’s elite institutions, standing by those commitments is very much the problem of the day.

March 4, 2026

America is at war with Iran — will our performing arts do their part to protest this act of senseless aggression? Or will it be business as usual?

In the March 26, 2025, “Ideas” section of The Boston Globe, Christopher Hoffman contributed a column with the headline “Eugène Ionesco Tried to Warn Us.” The piece observes how “avant-garde playwright Eugène Ionesco’s 1959 play Rhinoceros satirized blind acquiescence to fascism and groupthink. Unfortunately, the play’s moral is more relevant than ever.”

Did local theaters take this MAGA-sized hint to schedule a production of the play? No, perhaps because this tragicomic social parable about a collective embrace of totalitarianism isn’t a musical, or because it hasn’t been a recent hit Off-Broadway. Someone, somewhere must have been listening. To its artistic and political credit, Yale Rep is staging the script—using Derek Prouse’s translation, adapted by Frank Galati and directed by Liz Diamond—from March 6–28.

The plot centers on an alcoholic, unkempt antihero named Berenger, who watches in shocked horror as inhabitants of a small provincial town gradually turn into rhinoceroses. Those committed to society’s bourgeois satisfactions and the moral order are the first to metamorphose. The rampaging rhino pack—raging, thundering, and blaring—goes on to claim the bodies and minds of citizens across the political spectrum, from left to right, including lawyers, romantics, and government officials.

The populace’s submission to thoughtlessness symbolizes “community spirit triumphing over anarchic impulses,” a metaphor for the spread of mass insanity inspired by Nazism. Berenger is immune to the transformation—too eccentric, too marginal, too bohemian? At the end, he is completely alone, left to muse on the fate of standing apart: “People who hang onto their individuality always come to a bad end.” Torn between despair and defiance, Berenger resolves to do what he can to confront a society gone mad—“to put up a fight against the lot of them.”

February 25, 2026

Mike Oram, Elizabeth Steen, and Dennis Brennan performing in Which Side Are You On? at the Burren. Photo: Paul Robicheau

Along with words of encouragement, I have gotten flack over my conviction, stated (often) in my weekly column and theater reviews, that the arts have a responsibility to address the political challenges posed by our unprecedented times — a Christo-fascist kleptocracy’s attempt to throttle democracy. I have been told that critical writing about the arts should be inspiring, not dispiriting. One respected voice informed me that the last paragraph in my pan of SpeakEasy Stage Company’s production of Job was “unhinged” because I insisted that “it is time our stages, which claim to care about their communities, step up and put on dramas that express alarm, resistance, and dissent.”

To my detractors, I pose a question: What is the proper role for arts criticism during this unprecedented time in American history, when xenophobic authoritarianism, empowered by the forces of government, is on the march? At the moment, a record number of books are being banned from libraries, artists censored or barred from entry, and minority cultures targeted by official decree. To my mind, carrying on with business as usual is cowardice in the face of repression. The strongest arts critics of the past would not have been silent about what is happening today — if only because of the threat it poses to artistic freedom. H. L. Mencken insisted that the essential purpose of the critic was to ensure the creative freedom of the artist, to clear the ground of rubbish, which not only included excoriating mediocrity, but the tyranny of censorship.

A critic is not deranged to claim that our artistic community is, in general, choosing to look away from an existential crisis in governance. Our stages are not meeting the moment, not building on a revered tradition of performance art whose laudable goal was to unify opposition to a virulent ideology that intends to curtail free speech and creative freedom. It is not acceptable to play it safe, waiting the wannabe despots out, magically hoping that they will be pushed aside. The alternative — their triumph — is too tragic to contemplate.

As for an admirable example of local artists who are speaking out against autocracy, take a look at Clea Simon’s excellent feature on the concert series Which Side Are You On? May a thousand flowers of artistic dissent bloom.

February 18, 2026

Why are U.S. philanthropies among the elite institutions that have been disgracefully reluctant to take bold stances against the country’s slide toward authoritarianism? There are the usual culprits: a fear of retaliation and investigations from the Feds; a desire to be seen as maintaining ideological “neutrality”; a malaise fed by uncertainty about tactics; the need to “keep their heads down” and avoid any political fallout; and internal polarization among members of the boards of directors.

It is not enough to call out such cowardice, but also to begin to search for remedies. As we struggle through an era of tyranny, violence, and inequality, the MAGA crisis offers us an opportunity—for both the giving and receiving ends of philanthropy—to rethink, reshape, and revitalize the mission of charity. As David Callahan points out in an article in Inside Philanthropy, “The strategies that liberal philanthropy has been pursuing to achieve transformative change in America—which have heavily centered on identity and rights—have hit a dead end.” It is time to examine new directions, explore philanthropy’s activist potential seriously, and reimagine its critical role in democratic renewal.

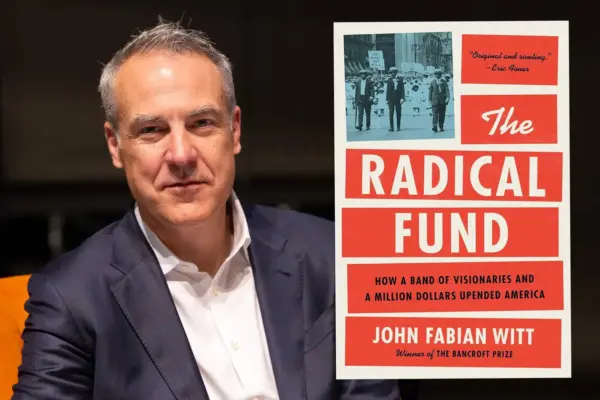

To build a better future for all, one place to start is by turning back to the past—a model of when American philanthropy directly engaged with the welfare of working-class people. John Fabian Witt’s fascinating book, The Radical Fund: How a Band of Visionaries and a Million Dollars Upended America, explores the creation, in 1922, of the American Fund for Pubic Service, which during its 19 years of existence gave away $2 million to a wide array of labor, racial equality, and civil liberties causes. Witt reports that one of the major purposes of the fund was “to identify and incubate the economic formation of the industrial union as something that would put tens of millions of Americans in a position to be able to control the direction of their economic lives and the lives of their families.”

The true test of American philanthropy’s courage is whether it empowers families to shape their economic futures—or stands by safely as that agency, and democracy itself, erodes further.

February 11, 2026

Horrific as it is, the auto-da-fé of book and arts coverage at The Washington Post has exposed a malaise that’s just as disheartening. No sizable media organizations are stepping up to pick up the slack. WBUR, WGBH, The Boston Globe — none has offered assurances (nor have other major U.S. outlets) that more book and arts reviews are coming. Don’t hold your breath. When the mainstream media bother to show even a faint interest in books and the arts, they lean into marketing rather than evaluation, fluff rather than serious coverage. Expect more inane interviews with artists by newspeople who don’t know a novel from their navel. You half expect to hear an NPR host ask a famous novelist: “Why did you decide to write a book featuring characters?”

You know things have hit rock bottom when Congress (!) is more protective of literature than our sputtering information industry. According to EveryLibrary, Congress’s final FY2026 “minibus” appropriations bills protect funding for the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives and Records Administration — a rejection of sweeping cuts proposed by the President that would have deeply harmed libraries, museums, and archives in every state. So our libraries will stand — at least for now — while elite communication conglomerates are content to let book reviews die.

Not on my watch. Viva La Book Review supports book critics by funding reviews in local media around the country. Besides donating to The Arts Fuse and other magazines producing high-quality book and arts reviews, now is the time to gather with other lit-lovers who are passionate about maintaining book culture — readers who believe in independent evaluation rather than servile boosterism. Bezos will only win if we let him. Let thousands of book reviews bloom, let thousands of critics contend.

— Editor Bill Marx

February 4, 2026

As Stanford University academic and theater artist Samer Al-Saber wrote in 2018, Palestinian stories are the “last taboo” in American theatre, and that fear has only grown more powerful with Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza.

In a recent article in American Theatre, two playwrights, Ismail Khalidi and Naomi Wallace, interviewed theatermakers in the West Bank and Gaza. What we learn is predictably sobering: reports of violence, intimidation, and destruction intertwined with cries of defiance. As Mustafa Sheta, producer and general manager of Jenin’s Freedom Theatre, asserts in the piece, “I do not see our work as a luxury but as an act of survival. When everything around us is being erased, theatre becomes a way to insist that imagination and collective memory still matter.” His belief in the role of theater is a reminder to our milquetoast companies that they should be doing more than marketing themselves as “bold” or “kind.”

Our media, like our theaters, is uninterested in life as it is lived in Gaza. Those of us who are concerned about what existence is like for those who have (at least so far) survived the conflagration should turn to Every Moment Is A Life, an innovative Arabic-English bilingual anthology that features heartbreaking remembrances and stories from 18 young Palestinian writers in Gaza. Edited by Palestinian-American scientist, writer, and activist Susan Abulhawa and Palestinian novelist and translator Huzama Habayeb, these short pieces offer visceral, detailed, and poignant descriptions of loss, love, and resilience amid apocalyptic devastation.

In 2024, Abulhawa ventured into Gaza twice, inviting people from displacement camps to share their experiences of living “zero to the bone,” of what it takes to maintain human dignity at a null point. No electricity, scarce food, no water, homes utterly demolished—and death omnipresent. As Rizq Ahmad writes in the opening of the title story: “In this era stripped of tenderness, where aggression knows no end and the bleeding of death never stops, affection and warmth among displaced families have become a sort of luxury. As we all sink into the mire of the daily struggle to survive, we keep moving from one place to another, clinging to a life that bears no resemblance to anything truly alive.”

Ahmad’s notion of an “era stripped of tenderness” for the powerless and targeted cuts close to home in Trump-era America. All proceeds from Every Moment Is a Life will be sent to the contributors in Gaza and to the Palestine Writes Literature Festival.

January 28, 2026

Actors Tom Ford and Patrick Harvey during a rehearshal session for the Portland Stage Company’s upcoming production of Lend Me a Tenor. Photo: Aressa Goodrich

I have long argued, too often for some people’s liking, that the Trump administration’s march toward authoritarianism has not been treated with sufficient alarm by the major players in New England’s artistic community. Perhaps this complacency – to cling to business as usual rather than to acknowledge dire threats to democracy and artistic freedom – will end after the ICE shootings in Minneapolis. Let’s hope it does.

Here’s one sign that creative organizations are beginning to connect with the threatened communities they claim to serve. I recently received an email from Arrowsmith Press with the subject line “Something Fast & Important We Can Do Before Jan 30.” There is a link to a Writers for Democratic Action Massachusetts’ “Call for Action” and the message “We need to work fast to get out the message that we will not stand for the murderous and illegal actions being taken against our neighbors, family, and friends across America.” Rather than send out yet another marketing blast, perhaps Boston’s cultural big shots might consider sending out similarly useful emails.

It will be interesting to see how Boston-area arts institutions respond to the crisis that’s coming our way, soon. ICE agents have begun working in Portland, ME — in an operation called “Catch of the Day” — and there are reports that children and people with no criminal record are being rounded up by what has become a rogue agency. What is the city’s major theater company, Portland Stage, staging during this emergency for the immigrant community? A production of Ken Ludwig’s farce Lend Me a Tenor. Portland Stage’s publicity tells us “we all need a good laugh.” I guess it all depends on who is included in that “all.” Residents hounded by ICE probably aren’t in the mood for yuks.

ICE may be coming, in force, to Boston. Will our leading artistic organizations be as depressingly oblivious to reality when the city’s streets are filled with illegal, perhaps even violent, police actions taken against our “neighbors, family, and friends”? Or will someone scrape up the courage to improvise alternatives — perhaps town halls that supply ways that Bostonians can organize against Trump’s wave of terror, or evenings dedicated to music, poetry, and drama that celebrate the value of the area’s immigrant communities? The choices our arts institutions make will be morally and civically revelatory.

January 21, 2026

In its email touting the 150th birthday of Jack London on January 12, the Library of America kicked off its homage by quoting the Wall Street Journal’s description of the writer as “illegitimate, handsome, wildly romantic, casting himself as the rebel and revolutionary.” London was also an unorthodox socialist, but the Library of America isn’t very interested in celebrating that aspect of his imaginative vision. The promo limits itself to mentioning the classic adventures The Call of the Wild and White Fang, along with London’s autobiographical novel John Barleycorn and The Road, an ode to turn-of-the-century hobos.

Given today’s violent, anti-democratic climate, highlighted by the Trump regime’s illegal and sadistic use of physical abuse in Minneapolis, LoA’s disregard for London’s political relevance is demoralizing. He adored the “scientific romances” of H.G. Wells, saluting him as a “sociological seer” for his imperialist satires, War of the Worlds among them. London experimented with a similarly dystopian brand of sci-fi that has proved surprisingly prescient. London’s 1908 novel The Iron Heel (which has never gone out of print) chronicles a fascist takeover of America, a bloody upheaval that will be unchallenged for 300 years. (The text is a memoir of rebellion defeated, love and loss, and despotism triumphant — a manuscript discovered hundreds of years later and published with scholarly notes in the twenty-seventh century.)

The authoritarian power grab is propelled by an unscrupulous oligarchy that has successfully curtailed freedom of speech and assembly, jailed dissenting opponents and critics, and taken over news and information industries. It maintains its power through a professional army of paid mercenaries who are assisted by a secret police force. Besides its considerations of religious fanaticism, imperialism, and terrorism, the rip-roaring narrative contains an international component as well — a small band of corporations have bonded together to assert global economic hegemony. To paraphrase Ezra Pound, literature is prophecy that stays prophetic.

London’s apocalyptic meltdown is crude, yes, but its elements of dark adventure are enormously cinematic. If only director Paul Thomas Anderson had decided to adapt (and update) London’s antifascist fantasia — the first modern novel to issue an alarm about dictatorship in America — rather than Thomas Pynchon’s Vineland. As one of the capitalists says, “We will grind you revolutionists down under our heel…the world is ours…and ours it will remain.” London’s class critique influenced Sinclair Lewis’ It Can’t Happen Here, George Orwell’s 1984, and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America. The book’s vision of gun-toting mayhem in the U.S. streets — revolutionary troops outnumbered by the military forces of the oligarchy — anticipates, in depressing ways, 21st-century mayhem. Those who are interested in reading The Iron Heel, along with London’s essays on socialism, “Revolution” and “How I Became a Socialist,” can find them in the LoA volume Jack London: Novels and Social Writings.

January 14, 2026

An existential battle for our eyeballs is being waged against the monetized-to-the-max machinations of our libertarian digital overlords, the pied pipers of algorithms. An intriguing part of the campaign to help our minds escape the clutches of the screen barons of Silicon Valley is being led by “an underground association of artists, performers, and interventionists” whose consciousness-freeing goals are proclaimed in the provocative manifesto ATTENSITY!: A Manifesto of the Attention Liberation Movement.

The group, which hopes to grow into a social movement, plans to flip the dominance of “an instrumentalized vision of human being,” propelled by technology’s “scramble to drive freehold stakes into the very stuff of our consciousness.” Instead, we are urged to use our various forms of attention, in the in-person communities we create, “to constitute the values of this world: what we care about, what we give ourselves to, what we endow with time and thought and touch, what we stay with, what we circle back towards; these are the things that become valuable.” Attention activism is about awakening people to the fact that we, not the “human frackers,” own our own minds.

Attempts to nurture independent, communal life outside the virtual bubble-world of an overpowering techno mind-suck are crucial. Still, the all-too-elastic boundaries of “attensity” give me pause. The volume’s authors define it as “the true gift of the open. It is where we meet in that openness, and make space for what unfolds.” Aside from the work of William James, no attention is paid to the literature on attention. Aldous Huxley’s 1962 utopian novel Island (his final book) contains mynah birds calling out “Attention.” For him, it was not about free-range “openness”; it was about cultivating a disciplined, spiritualized awareness of the present moment—being fully here and now rather than letting oneself become lost in memory, fantasy, or habit. Attention was not simply a matter of sharpening psychological concentration or joining with others to share interests and understanding. It was also an ethical imperative—to see reality, oneself, and others clearly. Attention was not about creating more space, but taking up the moral struggle of drawing responsibly humane boundaries.

January 7, 2026

When it comes to reflecting on what is happening around us, Boston-area theaters have hermetically sealed — aside from advising us to “be kind,” boldly staging Broadway hits, and bringing back, by popular demand, Joy Behar’s My First Ex-Husband. Few companies have dared to confront our ongoing American meltdown; those who do should be saluted. Of course, Boston’s critics should be demanding a slowdown in theatrical business as usual, but they are content to keep their heads buried in the confetti of happy talk. The Boston Globe stage critic assumes that it is dandy that Boston theaters stick with domestic matters — no one along the ideological spectrum will be bothered if the drama is kept all in the family.

So, kudos to the Writers for Democratic Action Theater Project for yesterday’s stirring January 6: A Day Forever, a staged reading directed by Jeff Zinn at the Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theatre. Co-writers James Carroll and Rachel DeWoskin adapted material from the Congressional Record of the second impeachment trial of Donald J. Trump. More low-hanging doc-u-drama fruit for a local troupe: former Special Counsel Jack Smith’s recent testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, defending his investigations into Donald Trump’s alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election and mishandling of classified documents. Smith asserted he had strong evidence of Trump’s culpability, that the Jan. 6 attack wouldn’t have happened without Trump.

I have my eye out for other stage efforts that tackle authoritarian chicanery or shows that acknowledge internationally uncomfortable realities. In March, Company One will be presenting, in partnership with the Boston Public Library, You Are Cordially Invited to the End of the World, a comedy about the climate emergency that a trusted authority informs me speaks, with humor and poignancy, “to the very real stakes of climate anxiety and grief without dwelling in hopelessness.” Serious theatergoers should support this as well as other productions that engage with the crises around us. Dramatist Dan O’Brien posits that a political play takes up “a problem that is ignored, denied,maligned. A political play is, by definition, unpopular.” Let us prove him wrong.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.