Arts Commentary & CD Reviews: On The Kennedy Center, Ben Folds, & Gustav Mahler

By Jonathan Blumhofer

What have Donald Trump and John F. Kennedy got in common? Besides the office they hold, not much. Certainly not an appreciation for the arts: Trump is to the field what McDonald’s is to fine dining.

It’s worth remembering that authoritarians often like to plaster their names wherever they can to project strength, especially when their hold on power grows electorally tenuous. Photo: Facebook

What’s in a name?

A lot, especially if you’re Donald J. Trump.

Our 45th and 47th president has an obsession with slapping his initials on things, and the latest victim of his depredations is one of the more unexpected: the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. On December 18, the Center’s board voted to approve adding the current occupant’s moniker to the venue and, come the next morning, crews were busy updating the building’s façade.

What have Trump and Kennedy got in common? Besides the office they hold, not much. Certainly not an appreciation for the arts: Trump is to the field what McDonald’s is to fine dining.

But rationalizing this sort of petty, childish behavior is a waste of time. Trump, blustering through the autumn of his life, clearly feels a need to leave behind some record of his existence. Thankfully, this one is unlikely to stick: only Congress, which created the Center, can rename it. And even given this 119th Congress’s slavish subservience to the head of a co-equal branch of government, efforts to officially do just that have, so far, gone nowhere.

Not that the move isn’t offensive; it is. Trump clearly holds nothing sacred but himself. His behavior last week demonstrated as much, beginning with his nauseatingly inappropriate thoughts on the murder of director Rob Reiner and ending with a desecration of what composer Leonard Bernstein once styled the “beloved memory of John F. Kennedy.” Even by Trumpian standards, that was quite a run of days.

But it’s also an insidiously dangerous tactic, an attempt to normalize the abnormal and inflate the power and presence of a politician whose policies are deeply unpopular and whose standing, by virtually every public indication, is in free fall.

It’s worth remembering that authoritarians often like to plaster their names wherever they can to project strength, especially when their hold on power grows electorally tenuous. Americans need to be alert to this tendency while time for a course correction remains, because, as with so much of this Administration’s assault on convention, decency, and taste — let alone its flaunting of the rule of law — there are no quick fixes. The serious legal and Constitutional questions these latest actions raise will have to be sorted out over time, by which point an unfathomable host of new outrages will have surely been perpetrated.

For those many millions exasperated by the juvenile antics of a 79-year-old man with unthinkable power at his fingertips and no filter to restrain him, at least the year hasn’t been a complete bust. As multiple No Kings Protests reminded, there’s strength in numbers. The common man’s money, too, speaks volumes: just ask ABC how their shameful attempt at censoring Jimmy Kimmel turned out.

In fact, the most potent and immediately accessible weapon to counter Trump’s overreaches and demagoguery is one that has been honed to near perfection this last decade by the likes of Kimmel, John Oliver, Stephen Colbert, and Alexandra Petri: mockery. “Against the assault of laughter,” Mark Twain once opined, “nothing can stand.” Now is the time to push that thesis to the max.

Such an approach is certainly fitting in the case of the Trump-Kennedy Center fiasco. At the same time, it needs to be balanced with some deeper understanding of what’s going on because, by itself, the approach risks minimizing the real damage the president’s takeover of the venue has wrought on the place’s administrative staff, its resident institutions, and artists who have come to rely on its role as a beacon for American culture.

President Donald Trump departs the White House en route to the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Wednesday, June 11, 2025, in Washington, DC. Official White House Photo/ Molly Riley

Though the new bosses have been reluctant to release any financial details, outside investigations and musician interviews suggest that audiences have been staying away from the nation’s arts center in droves and chicanery is afoot. Unsurprisingly, the finances of the Washington National Opera and National Symphony Orchestra, both of which call the Center home, are said to be struggling. And it’s hard to see how renaming the building will either help refill seats or restock those coffers.

As far as those two collectives are concerned, if ever there were a case of unwanted guilt-by-association, this seems to be one. Complaints that both groups should either pack up, leave, and find new homes or that, by staying, they’re complicit in the Administration’s abuses of power are equally simplistic and wrongheaded.

For one, there are no opera houses or concert halls in the area that could simply replace the Kennedy Center — and certainly not without disrupting other performing groups. Additionally, at least in the case of the NSO, a considerable amount of its funding is covered by the Center. Short a generous consortium of benefactors, its options are severely limited.

As to the second charge, KC interim president Richard Grenell’s ignominious swapping out of NSO concerts after Thanksgiving for FIFA’s World Cup kickoff says, at this point, everything one needs to know about this Administration’s view of the propagandistic value of the ensemble.

For both institutions, one of the few silver linings of the last year has been the lack of diktats about what to program (aside from the new requirement that the NSO start each concert with the National Anthem). Especially given the orchestra’s recent history as a champion of Black American composers, this is something to watch: if its programming independence is curtailed, alarm bells should go off. Until then, though, a middle course of some kind of continued support — for the ensembles, though not necessarily the Center itself — seems to be in order.

As it happens, a pair of NSO recordings out this year call attention to just what a fine, versatile group it is and what we stand to lose if it’s allowed to wither.

As it happens, a pair of NSO recordings out this year call attention to just what a fine, versatile group it is and what we stand to lose if it’s allowed to wither.

The first of those, released in July, features the NSO’s former artistic advisor, Ben Folds. The singer-songwriter was among the first of a bevy of leading talents to disassociate from the Kennedy Center following the president’s February coup. Though the politics of Ben Folds Live with the National Symphony Orchestra can be inferred, the recording itself is anything but an angry screed.

Rather, it’s a thoughtful reworking of various songs spanning a good chunk of Folds’s career, from 2001’s Rockin’ the Suburbs (“The Luckiest” and “Still Fighting It”) to 2023’s What Matters Most (“But Wait, There’s More,” “Fragile,” and “Kristine From the 7th Grade”). The results, taped in October 2024, are by and large successful in judiciously integrating the symphony orchestra into the world of popular song.

Sure, some of the tracks lay it on a bit thick: the climax of “Kristine,” for instance, is a bit over the top. The full-orchestra version of “Still Fighting It” doesn’t pack the immediacy or edge of the first, band-sized edition.

At the same time, Folds’s duet with Regina Spektor in “You Don’t Know Me” is electric. The scoring of “Capable of Anything” is fresh (that number transfers conspicuously well from the original, played by yMusic on the 2015 album So There) and several items — particularly “Kristine” and “Still” — demonstrate Folds’s uncanny mastery of the wistful, triple-meter ballad: in them, lyrical invention and melodic grace go hand-in-hand.

Through it all, Folds’s rapport with and appreciation for the NSO is palpable. He, the orchestra, and the audience are clearly having a blast. What could possibly disrupt such a beautiful partnership?

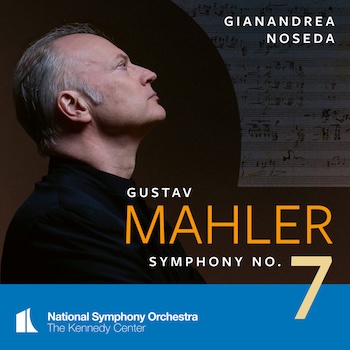

A couple of months earlier, the orchestra and music director Gianandrea Noseda taped Mahler’s Symphony No. 7. The Seventh is easily the composer’s strangest symphony, picking up, as it does, the pieces left over from the shattered end of the Sixth. As such, there’s a sense of disorientation built into its DNA: tangy dissonances, shadowy textures, and a feeling of being simultaneously grounded but off-balance mark many of its pages. As such, the score makes for a particularly apt — if, ultimately, overly optimistic — soundtrack to this perplexing year.

A couple of months earlier, the orchestra and music director Gianandrea Noseda taped Mahler’s Symphony No. 7. The Seventh is easily the composer’s strangest symphony, picking up, as it does, the pieces left over from the shattered end of the Sixth. As such, there’s a sense of disorientation built into its DNA: tangy dissonances, shadowy textures, and a feeling of being simultaneously grounded but off-balance mark many of its pages. As such, the score makes for a particularly apt — if, ultimately, overly optimistic — soundtrack to this perplexing year.

Noseda isn’t a conductor one immediately associates with Mahler, but his grasp of the Seventh is, for the most part, excellent. Only at a couple of related junctures in the first movement do some fussy massagings of tempos and phrasings draw attention to themselves and threaten to grind the proceedings to a halt.

Those spots excepted, his reading is persuasive and the NSO’s playing excellent. The three middle movements, breathtakingly lean and well-directed, are especially fine and nobody sweats the boisterous finale. That section is often dismissed as second-rate Mahler, a charge I’ve never been able to understand: the man didn’t do second-rate. In this performance, it certainly doesn’t sound anything less than brilliant, especially as the music weathers various threatening storm clouds and, at the very end, decisively swats away one last threat.

One might be tempted to read into that Rondo a prophecy of what, eventually, will transpire for the NSO, WNO, Kennedy Center, and the larger United States. That is certainly something to hope and fight for. But the closing lyric in Folds’s “But Wait, There’s More” offers a sobering assessment of how far we’ve allowed ourselves to fall and provides a fitting epitaph for the year just ending: “Not sure that we can take too much more,” he sings. “Pray that there’s a bottom somewhere in sight/Brothers and sisters, hold tight.”

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Ben Folds, Donald J Trump, Gianandrea Noseda, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts